Thirty years of crisis: Romania’s demographic situation

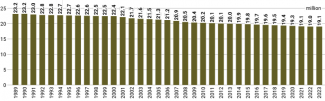

Over the past three decades, Romania has been among the fastest-depopulating countries in the European Union. Between the beginning of its political and economic transition and 2021, the country lost as much as 17% of its population. During this period, Romania’s population decreased by an average of 130,000 people per year – the equivalent of a medium-sized Romanian city. This trend has been driven primarily by mass emigration, mainly for economic reasons, as well as a negative natural population growth rate, with deaths now outnumbering births by approximately two-thirds. Although immigration from outside Europe has been increasing, it remains marginal, temporary, and insufficient to reverse the country’s negative demographic trajectory. Despite a brief halt in population decline during 2022–2023, due to a positive balance of return migration, the downward trend is expected to continue. Over the next 25 years, Romania’s population could decline from 19 million to approximately 16 million.

The evolution of the demographic situation

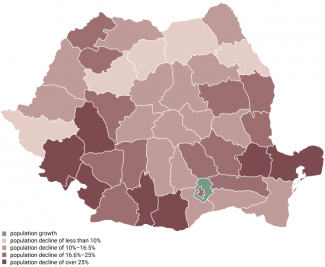

From the end of the Second World War until the collapse of the communist regime, Romania’s population grew at a remarkable pace. In 1946, the country had around 15.6 million residents. By 1990, shortly after the fall of Nicolae Ceaușescu’s regime, this figure had risen to nearly 23.2 million – an increase of almost 50% over 44 years. However, with the onset of political and economic transformation, a sharp population decline began – a trend that continued until recently. According to the 1992 census, Romania’s population stood at 22.8 million. By 2002, it had dropped to 21.7 million, and over the following nine years it fell by a further 1.5 million, reaching just over 20.1 million in 2011. The most recent census, conducted in 2021, recorded a population of approximately 19 million – a level last seen in the mid-1960s.[1] Depopulation has affected nearly all regions of the country; however, the decline has been particularly severe in the southern counties. Teleorman, Olt, Brăila, Tulcea, and Hunedoara each lost more than 25% of their population by 2021 (see map). The only county to record population growth during this period was Ilfov, which surrounds the Romanian capital.[2]

Chart 1. Romania’s population between 1989 and 2023

Source: World Bank.

A halt – and even a modest reversal – of the negative trend occurred at the beginning of 2023. According to data from Romania’s National Institute of Statistics, the number of residents (that is, the population permanently residing in Romania, regardless of citizenship) rose by approximately 9,000 year-on-year, reaching 19,051,562 on 1 January 2023. One year later, at the beginning of 2024, the figure increased again, this time by nearly 10,000. In both instances, the change was driven by an unusually positive migration balance, primarily due to return migration. In 2022 and 2023, the number of individuals entering the country exceeded those departing by almost 85,000 and 82,000 respectively. However, this development appears to be a temporary fluctuation rather than an indication of long-term improvement.

Map. Population change dynamics by county, 1992–2021

Source: R. Santa, A. Coșciug, ‘România în 2023. Spre o nouă realitate demografică’, Rethink România, 2 November 2023, sourced from: media.hotnews.ro.

Causes of the crisis: mass emigration…

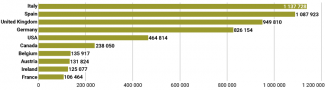

The primary driver behind Romania’s dramatic population decline is mass labour-related emigration. According to World Bank estimates, at least 4 million Romanian citizens – roughly 20% of the total population – reside abroad, either permanently or seasonally.[3] Some public institutions, including the Romanian Ministry of Foreign Affairs, claim the actual figure is significantly higher, estimating it at 5.7 million.[4] The highest estimate comes from the government’s Department for Romanians Abroad, whose head stated in 2022 that as many as 8 million Romanians may be living outside the country.[5]

The first wave of emigration occurred in the 1990s, triggered by the collapse of the national economy and facilitated by the opening of borders following the fall of the communist regime. Within just three years, Romania’s GDP fell by 40%, from $41.45 billion in 1989 to only $25 billion in 1992. The crisis persisted for over a decade, and it was not until 2002 that the authorities in Bucharest succeeded in restoring GDP to pre-transition levels and setting the economy on a path of relatively stable growth. By that time, however, at least 335,000 Romanians had left the country, according to official – though likely underestimated – figures.[6]

In the years immediately following the fall of the communist regime, Romania’s population decline was also driven by ethnically motivated economic migration. This involved minority groups residing in Romania who, due to their ethnic origin, were eligible for repatriation programmes and able to relocate to significantly wealthier European countries following the opening of borders. As part of this process, the local German population – which had been settled in Romania for several centuries – almost entirely disappeared.[7] In 1990 alone, 60,000 ethnic Germans left the country, accounting for 60% of all emigrants that year.[8] According to the 1992 census, approximately 120,000 Germans remained in Romania. A decade later, that number had halved to approximately 60,000, and currently stands at around 23,000. A similar pattern emerged among the Hungarian ethnic minority, the largest in Romania. Between 1992 and 2002, their population declined by roughly 200,000, or 12%.[9]

The improvement in Romania’s economic situation in the early 2000s did not stem the outflow of people. On the contrary, it coincided with the European Union’s liberalisation of visa regulations for Romanian citizens, who were now free to enter Schengen Area countries without restrictions. Combined with significantly lower wages compared to Western Europe, this development further accelerated labour migration. Some researchers estimate that between 2002 and 2007 alone, more than 2 million Romanians left the country, primarily for Italy.[10] Another major wave of emigration, involving at least 1 million people, occurred after Romania joined the EU in 2007 and most member states opened their labour markets. One notable exception was the United Kingdom, which did not lift employment restrictions for Romanian citizens until 2014.

Chart 2. Key destinations of Romanian emigration

Source: ‘Date statistice cu privire la cetățenii români cu domiciliul sau reședința în străinătate, la sfârșitul anului 2021’, Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Romania, diaspora.gov.ro.

Romanians who have chosen to leave their homeland predominantly reside in four countries. Italy has remained the most popular destination for years, hosting over 1.1 million Romanian citizens. This preference is driven not only by economic factors such as a developed economy and high wages, but also – primarily – by cultural and linguistic proximity. As a Romance language, Romanian is closely related to Italian, which facilitates communication and accelerates the integration process. Spain is home to a slightly smaller but comparable Romanian community, and is attractive for the same reasons as Italy. The United Kingdom and Germany rank third and fourth, respectively, in terms of Romanian migrant populations (see Chart 2).

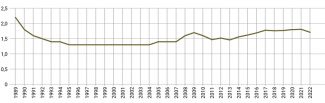

…and a low birth rate

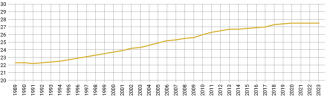

The phenomenon of mass labour migration is compounded by a low birth rate, which is insufficient to ensure generational replacement. In 1989, Romania’s fertility rate stood at 2.2 children per woman. Merely two years later, it had fallen to 1.6, and by 1995 it had reached a historic low of 1.3.

Chart 3. Fertility rate trends between 1989 and 2022

Source: Eurostat, World Bank.

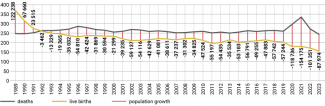

The main causes of Romania’s declining fertility rate were the country’s poor economic situation and the prolonged economic crisis that persisted throughout the first decade following the fall of communism. This environment fuelled a sense of uncertainty, discouraging people from starting families. Labour migration, which primarily involved individuals of reproductive age, further exacerbated the decline. As a result, the number of births fell from nearly 370,000 in 1989 to 260,000 in 1992, and to just 237,000 in 1995.

The economic growth experienced in the early 2000s led to some improvement, including a modest increase in the birth rate, which eventually stabilised at 1.7 in 2017. Although this figure is relatively high by EU standards – exceeded only by France and above the 2022 EU average of 1.46 – it remains below the threshold required for generational replacement.[11] The impact is clearly visible in the widening gap between births and deaths. Persistently low fertility, coupled with a relatively stable number of deaths, has led to a consistent natural population decline in Romania since 1992. On average, the country has lost approximately 50,000 people per year due to natural demographic trends alone. Between 1992 and 2023, this amounted to a loss of over 1.6 million people – out of a total population decline of 3.8 million during that period[12]. The COVID-19 pandemic years were particularly severe. In 2020, 2021, and 2022, the gap between births and deaths reached approximately 119,000, 154,000 and 101,000 respectively.

Chart 4. Trends in births and deaths between 1989 and 2023

Source: Romania’s National Institute of Statistics

Beyond economic factors, other issues have also contributed to the decline in birth rates, including the radical liberalisation of abortion laws. These had been strictly enforced under the Ceaușescu regime since 1966, but were relaxed after 1989. Broader socio-cultural changes – typical of all developed countries – have also played a role. One clear indicator is the rise in the average age at which women have their first child, which increased from 22.3 years in 1989 to 27.5 years in 2023. Labour migration and Romania’s growing exposure to Western culture after 1989 began shaping people’s expectations regarding living standards, infrastructure, healthcare, and educational opportunities for their children as early as the 1990s. Public opinion surveys indicate that it is precisely the poor quality of these services – in comparison with those available in Western Europe – that discourages many Romanians from having children. This is further evidenced by the fact that birth rates among Romania’s diaspora are significantly higher than within the country itself. In 2014, the fertility rate among Romanian women residing in the United Kingdom was nearly double that of those in Romania (which at the time stood at 1.56), reaching 2.93 children per woman.[13]

Chart 5. Trends in the average age of mothers at first birth, 1989–2023

Source: Romania’s National Institute of Statistics.

The government’s (silent) response

Romania’s deteriorating demographic situation – driven primarily by the mass emigration of working-age individuals – is leading to an increasingly acute labour shortage. In response, the country has gradually begun to open up to labour migrants. Between 2013 and 2022, the number of work permits issued to non-EU nationals tripled, reaching 31,000 per year. Romania has become particularly attractive to labour migrants from Asia. In 2022, Nepalese citizens received 6,700 permits, accounting for 22% of the total issued that year. A further 5,200 permits (17%) were issued to Sri Lankans, and 2,600 (8.4%) to Bangladeshi nationals. Despite this growing openness to expatriate workers, the number of labour migrants currently residing in Romania remains low, not exceeding 115,000 – equivalent to 0.6% of the total population, or less than 3% of the population lost since the start of the transition. Moreover, Asian workers do not typically intend to settle in Romania on a permanent basis. As a result, immigration can not compensate for the demographic deficit accumulated over the past 30 years.

Another measure aimed, in part, at addressing Romania’s demographic challenges is the long-standing policy of granting Romanian citizenship to residents of the Republic of Moldova and parts of Ukraine – specifically the Chernivtsi and Odesa regions – which were part of Romania during the interwar period. Under current legislation, descendants of Romanian citizens who lost their citizenship due to the 1940 Soviet annexation of these territories may ‘recover’ Romanian nationality without fulfilling additional requirements, such as renouncing their existing citizenship.

Under these legal provisions, Bucharest has issued more than one million passports to date, the vast majority – between 80% and 90% – having been granted to citizens of the Republic of Moldova. Officially, these measures are presented as an effort to correct a ‘historic injustice’ and as a demonstration of solidarity with Moldovans, whom the Romanian government considers part of the Romanian nation. In practice, however, the authorities also hoped to encourage at least some residents of Moldova to relocate to the comparatively wealthier Romania. This objective has not been achieved. Moldovans have applied en masse for Romanian passports, viewing them primarily as a gateway to EU citizenship and, with it, access to employment opportunities in Western Europe. As a result, according to Moldova’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs, of the approximately 1.2 million Moldovans working abroad, only around 19,000 – merely 1.6% – reside in Romania.[14]

At the same time, the Romanian government has introduced certain measures aimed at encouraging higher birth rates. However, these efforts remain rather limited. Large families are eligible for tax relief and receive a ‘Large Family Card’, which provides access to a range of discounts. The state also provides modest monthly child allowances, which, from 2025, will amount to €160 per month for children up to the age of two, and €65 for those aged two to eighteen. In addition, women in challenging life circumstances may receive a one-off payment of approximately €400 upon the birth of a child. The authorities are also investing in childcare and early education infrastructure, including nurseries and kindergartens.

What Romania lacks, however, is a coherent pronatalist strategy. One key factor limiting public and political engagement with policies relating to fertility is the enduring societal trauma associated with the so-called Decree 770. Issued in 1966 at the behest of Nicolae Ceaușescu, the decree was intended to trigger a sharp increase in the country’s population. It severely restricted access to contraception and almost entirely prohibited abortion. It also introduced mandatory, routine checks in workplaces to monitor whether female employees were pregnant. The legacy of this policy – including abandoned children and the widespread deaths of women who underwent illegal abortions – has left a profound imprint on the Romanian collective memory. As a result, there is considerable societal resistance to any perceived state interference in reproductive matters.

The issue of demographic decline, which has afflicted the country for years, features in the political agendas of all major political parties. They unanimously declare a commitment to increasing birth rates and encouraging the return of Romanian labour migrants. Radical right-wing parties, such as the Alliance for the Union of Romanians (AUR) – currently the second-largest political force in parliament, holding 18% of seats in both chambers – place particular emphasis on preserving the country’s ‘national substance’, making it a central theme of their political agenda. While the AUR is vocally critical of abortion, it does not advocate tightening Romania’s liberal abortion laws, recognising that such a position is broadly unpopular among the public.

Prospects

All indications suggest that Romania’s demographic situation will continue to deteriorate, although the rate of population decline is likely to slow significantly. The positive trend observed over the past two years – when the population increased by approximately 10,000 annually – is most likely temporary, and the result of several coinciding factors. These include the return of some migrants from European countries affected by economic difficulties (notably Spain), the arrival of Ukrainian refugees, and a significant increase in the number of labour migrants entering Romania. In the absence of proactive government measures to boost fertility, an increase in the birth rate remains unlikely.

Although less intense than in previous years, Romania’s population will continue to decline due to migration. Despite a clear improvement in economic conditions and rapid development over the past two decades – between 2002 and 2023 the country’s GDP increased nearly eightfold, while GDP per capita in purchasing power parity rose sevenfold – many Romanians, particularly younger individuals, remain interested in emigrating, at least temporarily. According to a 2024 survey, nearly half of Romanians aged 14 to 35 express a desire to move abroad. Most of them – approximately 25% – are considering temporary labour migration. A further 13% plan to study in another country, while 10% intend to settle abroad permanently. The main reason cited for emigration is the disparity in quality of life. Approximately 38% of respondents stated that they were motivated by the living standards available in destination countries. One in five wish to earn enough to purchase a property in Romania, while an equal proportion state they wish to emigrate because they are dissatisfied with the direction in which the country is heading.[15]

The high unemployment rate affecting Romania’s younger population is one of the key factors influencing their desire to emigrate. In August 2024, over 23% of individuals under the age of 24 were officially unemployed.[16] Despite the country’s economic growth, Romanian wages – alongside those in Bulgaria – remain among the lowest in the European Union. In 2023, the average annual net salary in Romania stood at €11,105 – nearly three times lower than the EU average of €28,217. It also lagged behind salaries in other countries in the region, including the Czech Republic (€17,168), Poland (€14,425), and Hungary (€12,456).[17]

These negative trends are reflected in projections from Romania’s National Institute of Statistics, which estimates that by 2050 the country’s population will decline to approximately 16 million. According to the forecast, 77% of this decline will result from natural demographic processes, with the remaining 23% attributed to continued emigration. The United Nations offers similar projections, forecasting a population of approximately 16.4 million by mid-century. In reality, however, the final figure may turn out to be somewhat higher. As Romania’s economic situation continues to improve and wages gradually rise – leading to improved living standards – the country may become an increasingly attractive destination for labour migrants. Given the growing labour shortages caused by demographic decline, Romania is also likely to adopt a more open approach to immigration in the years ahead.

[1] Unless otherwise stated, all demographic data are sourced from Romania’s National Institute of Statistics.

[2] The population growth in Ilfov County was driven by the relocation of residents from the capital to the suburbs, as well as internal migration from rural areas to the vicinity of Bucharest.

[3] ‘Romania. Systematic Country Diagnostic. Background Note. Migration’, World Bank, June 2018, worldbank.org.

[4] ‘Cel puţin 8 milioane de români se află în afara graniţelor ţării – secretar de stat’, Economica.net, 19 May 2022.

[5] These estimates appear significantly inflated. Florin Cârciu, head of the Department for Romanians Abroad, who claims that as many as 8 million Romanians live outside the country, most likely includes within this figure ethnic Romanians residing primarily in the Republic of Moldova and Ukraine. This group numbers just under 3 million. When combined with World Bank and Romanian Foreign Ministry estimates concerning labour migrants, the total could indeed amount to approximately 7–8 million people.

[6] I. Horváth, R.G. Anghel, ‘Migration and Its Consequences for Romania’, Comparative Southeast European Studies, vol. 57 (2009), H. 4, pp. 386–403.

[7] The sharp decline in Romania’s ethnic German population began well before 1989 and was primarily the result of a deliberate policy pursued by the country’s communist authorities under Ceaușescu. The regime issued exit permits to ethnic Germans in exchange for financial compensation paid to Bucharest by the government in Bonn. As a result, the German minority declined from 383,000 in 1966 to just 120,000 by 1990.

[8] I. Horváth, ‘Immigration and Emigration since 1990’, Bundeszentrale für politische Bildung, 1 January 2010, bpb.de.

[9] Their current number stands at around 1 million, representing a decline of nearly 40% over the past 30 years (1992–2021).

[10] T. Judah, ‘Romania’s demographic tailspin heralds social change’, Balkan Investigative Reporting Network, 28 November 2019, balkaninsight.com.

[11] ‘Total Fertility Rate in EU’, Eurostat, ec.europa.eu.

[12] If Romania lost 1.6 million people due to natural demographic processes between 1992 and 2023, and the total population declined by 3.8 million over the same period, it might reasonably be assumed that the number of emigrants would stand at 2.2 million, rather than the previously cited 4 or 5 million. This discrepancy arises from the fact that a significant number of emigrants participated in the national census. Some were counted while temporarily back in the country – for example, during holidays or seasonal work – while others used the remote response option.

[13] S. Doughty, ‘Polish mothers have more children once they come to Britain: Birth rate among migrants is two third higher here than in their homeland’, Daily Mail, 4 February 2014, dailymail.co.uk.

[14] N. Paholinițchii, ‘Câți cetățeni ai Moldovei sunt în străinătate? Diaspora moldovenească în UE, Rusia și în lumea întreagă’, NewsMaker, 7 July 2021, newsmaker.md.

[15] D. Popa, ‘Aproape jumătate din tinerii români își declară intenția de a emigra. Anul trecut s-a înregistrat recordul ultimilor 10 ani la plecări definitive din țară ale tinerilor’, HotNews.ro, 16 August 2024.

[16] C. Chiriac, ‘România, campioană la șomaj în rândul tinerilor. Peste 23% nu muncesc’, Capital, 4 October 2024, capital.ro.

[17] S. Yanatma, ‘European average salary rankings: Where does your country stand?’, Euronews, 8 July 2024, euronews.com.