The second front

I. THE MACROECONOMIC SITUATION

IV. CHARACTERISTICS OF SPECIFIC SECTORS

V. TRANSPORT: OPPORTUNITIES AND RISKS FOR POLAND AND THE EU

1. Short- and medium-term perspectives (until the war’s end)

2. Long-term perspectives (after the war)

Trade in agri-food products with Poland

MAIN POINTS

- The Russian invasion has caused the largest economic collapse in Ukraine’s history. Its GDP fell by nearly 30% in 2022, although the government has managed to maintain the country’s macroeconomic and financial stability. Although forecasts for this year and next predict economic growth rates of several percent, no significant economic recovery should be expected as long as military operations on the current scale combined with the steady stream of missile attacks continue.

- The relative stabilisation of Ukraine’s budget would have been impossible without financial support from Western countries and international financial institutions. This reached over $32 billion in 2022, and had already amounted to $28 billion by mid-August this year. The EU and the United States are the key donors; they have provided a total of nearly $40 billion in the form of grants and low-interest loans since the beginning of the war. The main challenge for Kyiv will be to maintain support at such high levels over the coming years.

- The invasion has led to the collapse of Ukraine’s foreign trade, especially exports. It also caused significant changes in the geographical structure of goods trade. Since Russia blocked Ukraine’s ports, they have lost their status as the country’s main export gateway, while before the full-scale invasion they accounted for two-thirds of foreign sales. Railways and road transport have recently gained in importance, since they have been used to ship most goods to and from Ukraine’s western neighbours. In this way, the EU has strengthened its position as Kyiv’s main trading partner, and in 2022, for the first time in history, Poland became its most important trading partner.

- As a result of the invasion Ukrainian agricultural production has shrunk significantly, in terms of both the area cultivated and the harvest yielded. The war has particularly affected the southern and eastern areas of the country. At the same time, exports of agricultural produce, which before February 2022 accounted for around 40% of total exports, have fallen by only 15% because the grain corridor through the Black Sea operated between 1 August 2022 and 17 July 2023, and new sales routes were also found. In the first half of this year agricultural production accounted for over 60% of total Ukrainian exports.

- As a consequence of the Russian invasion, Ukraine has become almost completely self-sufficient in satisfying the demand for natural gas, due to a relatively small reduction in its own production combined with a significant decline in internal consumption. This has happened because several million people have left the country, and numerous enterprises (especially heavy industry) have limited or ceased their operation as a result of the war.

- The fuel deficit that affected Ukraine in mid-2022 was averted by redirecting all available means of transport to import fuel from EU countries. Priority service for vehicles transporting these goods across the border was also ensured, and the Polish side allocated half of the Dorohusk road crossing exclusively to handling the transport of fuels & LPG. The two main corridors for fuel imports ran from Poland directly and as a transit route via Poland and Romania. As a result, the geographical structure of fuel imports has changed completely. Before the war, Ukraine imported only 21% of fuels from the EU, but in the first half of 2023 this share reached 61%.

- The Ukrainian power system managed to survive intense rocket fire between October 2022 and March 2023, but the damage is very extensive. Despite the renovations carried out in recent weeks, the country increasingly needs emergency electricity supplies from its neighbours, primarily Poland, Romania and Slovakia, hence the importance of the 400 kV line between Rzeszów and the Khmelnytskyi Nuclear Power Plant which was put into operation in May this year. We can expect Russia to resume shelling Ukraine’s energy infrastructure during the heating season starting in October, with the aim of causing blackouts throughout the country.

- Metallurgy, which used to be an important sector of the economy and a source of significant export revenues, has suffered particularly as a result of the war. Exports have been largely suspended due to the blockade of the Black Sea ports. Some of the metalworking plants have been destroyed during the hostilities, and the rest are located in the eastern part of the country, close to the front line. As a result, production has dropped by 70–80% compared to the pre-war period, and it seems that it will not be possible to increase it significantly before the ports reopen.

- IT is the only important sector of the economy to have been growing so far, in terms of both exports of services and its share of GDP, despite the Russian invasion. The industry quickly adapted to war conditions and manifested great flexibility and resilience. The technology sector in Ukraine has been growing steadily since 2012, when IT production was legally exempt from VAT for 10 years. Currently, it is receiving special support from the government as it operates under a special legal and tax regime.

- The Ukrainian defence industry has been almost completely destroyed. Due to the war, the arms potential at the state’s disposal had to be changed and the focus had to be shifted to the current needs of the fighting troops. Ukraine will not rebuild its position as an important player on the international weapons market in the foreseeable future, due both to external competition and the highly probable shortage of its own funds for further investments.

- The network of transport connections will have a great impact on Ukraine’s economic and trade bonds with Poland and the wider EU. The routes running through Poland will be crucial to including Ukrainian companies in Western supply chains, as well as for the import of materials necessary for the process of Ukraine’s reconstruction. At the same time, efforts should be made to shape bilateral relations, combined with Ukraine’s European integration process, so as to ensure a level playing field for Polish and Ukrainian transport companies (the latter currently enjoying special privileges) on the EU market.

I. THE MACROECONOMIC SITUATION

1. GDP

The hostilities led to the largest economic collapse in the history of independent Ukraine, which in 2021 had just begun to recover from the recession caused by the COVID-19 pandemic. In the first quarter of 2022 GDP decreased by 14.9%, but in the next quarters the declines were over 30% compared to the same periods in 2021, and over the whole of 2022 the economy shrank by 29.1%. Although this result is much better than the first forecasts at the start of the Russian invasion, which predicted a decline of 45%, the war still caused a huge shock to the economy.

Chart 1. Quarterly change in Ukraine’s GDP in 2019–2023

Source: State Statistics Service of Ukraine.

In the first quarter of 2023, the decline in GDP slowed down to 10.5%, because it was calculated in reference to the first quarter of 2022 when military operations had already been ongoing for over a month. Forecasts for this year have been revised frequently, and they currently estimate growth at 1–4.7% and 3.2–5.1% in 2024 (see table 1).

Table 1. Ukraine GDP forecasts for 2023 and 2024

Source: Centre for Economic Strategy.

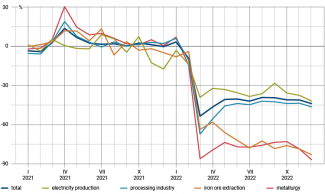

2. Industrial production

The economic collapse has affected industry especially strongly: throughout 2022, production fell by 36.7%, and in the first months of the war by over 50%. Metallurgy has been hit hard, and its production has dropped by nearly 80% since the outbreak of the war. Meanwhile, the invasion has affected iron ore extraction to a lesser extent.

Chart 2. Dynamics of Ukraine’s industrial production and selected sectors in 2021 and 2022

Source: State Statistics Service of Ukraine.

The blockade of Ukrainian ports led to a significant reduction in iron ore extraction as most of the production used to be shipped by sea, and finding alternative supply routes proved difficult. This factor also played a large role in the case of metallurgy, but the situation was exacerbated by direct damage: the second and third largest metallurgical plants in Mariupol (Azovstal and Ilyich MMK) were destroyed, along with many other facilities. In total, according to estimates by the Kyiv School of Economics, direct losses in industry reached $11.4 billion by June 2023.

3. Inflation

The Russian invasion caused a surge in inflation in Ukraine. The Consumer Price Index rose from 10% at the beginning of 2022 to 26.6% at the end of that year. From that moment on it has been rising at a slower rate, and in July this year inflation fell to 11.3%. Considering Ukraine’s economic problems, the increase in prices has not been unusually high; however, it has not been evenly distributed among all groups of goods. The public has been hit particularly hard by the rising prices of food (well above the average price index) and transport as a result of the fuel supply problems caused by the destruction of refineries in the country and logistical difficulties in bringing in imports. To mitigate the effects, the government has imposed a ban on rising gas and heating prices for individual customers during the period of martial law and six months after its end. In addition to this, electricity tariffs for individual customers were frozen until June this year.

Chart 3. Monthly inflation in Ukraine (y/y) in 2022 and 2023

Source: State Statistics Service of Ukraine.

Prices have been rising much more slowly than expected. This may result in lower tax revenues than planned, as the 2023 budget assumes an inflation rate of 28.4%. According to current forecasts, it will stand at 10–15% this year and around 10% next year.

Table 2. Inflation forecasts for 2023 and 2024

Source: Centre for Economic Strategy.

II. INTERNATIONAL AID

The economic crisis has had a huge impact on the budget: on one hand tax revenues have decreased, while on the other security and defence expenses have increased dramatically. Ukraine’s survival as a state would not have been possible if not for the support from the broadly understood West and international financial institutions.

The Ukrainian budget has mainly been supported by the US and the EU. From the beginning of the Russian invasion until mid-August this year, the United States provided Kyiv with $20.5 billion and the EU $19.4 billion. The total international financial support offered to Ukraine in the form of low-interest loans and grants stood at $32.1 billion in 2022 and $28.1 billion in 2023.

Table 3. Foreign partners’ financing of Ukraine’s budget in 2022–2023 (in millions of dollars, as of 16 August 2023)

Source: Ministry of Finance of Ukraine.

Although foreign support for Ukraine is high, it is not enough to close the entire budget gap. Kyiv has been forced to issue internal bonds, which are mainly being purchased by the National Bank of Ukraine. This effectively means printing hryvnias. This practice has recently been limited due to commitments made to the IMF. Despite this, bonds worth $9.6 billion have been issued since the beginning of 2023.

$59.3 billion is needed for this year’s budget, while the received and declared foreign financial support currently stands at $42.1 billion. Even if bonds are added to this sum, a $7.6 billion gap still remains, and for now it is not clear how it will be filled.

Chart 4. Budget deficit and foreign financial support

Source: Centre for Economic Strategy.

III. CHANGES IN FOREIGN TRADE

2022 saw a very serious collapse in exports (-35.1%) and imports (-24.2%). Along with the direct consequences of the war, such as the loss/occupation of part of the territory and the destruction of export-oriented industries, the collapse has mainly resulted from the Russian blockade of the Black Sea ports which had been used to transport about two-thirds of Ukraine’s exported goods before the invasion.

In August 2022, the ban on imports of Ukrainian agricultural products was lifted, although it was still applied to other key exports such as iron ore and metallurgical production. On 17 July this year, Russia withdrew from the grain deal, which significantly limited Ukraine’s foreign trade in agricultural produce.

Chart 5. Comparison of exports and imports of goods in 2021 and 2022

Source: State Customs Service of Ukraine.

The Russian invasion led to the collapse of Ukraine’s trade: exports dropped by 49.5% and imports by up to 70.7% in March 2022. One reason was that Russia and Belarus had been important economic partners for Kyiv before the war, especially in terms of fuel imports. In the months following the invasion, import levels partially stabilised; at the end of the first half of 2023, they were 6.3% higher than a year earlier, and exports shrank by 5.7%.

Chart 6. Monthly dynamics of Ukrainian exports and imports in 2022 and in the first half of 2023

Source: State Statistics Service of Ukraine.

River transport via the Danube, as well as road and rail transport, have gained importance as a result of the blockade of the Black Sea ports. The routes running through the land border crossings with the EU, primarily with Poland, have become Ukraine’s main routes for foreign trade. Road transport is now playing an especially important role: in July 2022 it accounted for around 75% of imports of goods, and this share has been increasing ever since.

The situation has affected Kyiv’s trade with its partners in various ways. In 2022, exports to the EU rose by 1.7%, which strengthened the EU’s position as the most important market for Ukrainian goods (64% of Ukraine’s foreign sales). Exports to other regions of the world have fallen off, sometimes to a very large degree (69% in the case of China, and 64% in the case of India). At the same time, it became necessary to search for alternative sales markets due to the port blockade, which resulted in an increase in sales to all Ukraine’s neighbours during 2022: to Romania by 150%, to Slovakia by 51%, to Hungary by 40% and to Poland by 27%.

Chart 7. Comparison of exports and imports of goods in 2021 and 2022 for individual regions

Source: State Customs Service of Ukraine.

The situation with imports is slightly different: the EU is the source of 51% of imports of goods to Ukraine, and imports from all other regions except the Middle East have been falling. Ukraine’s imports of goods were lower than in the previous year, but the changes were not dramatic because Ukraine primarily purchases highly processed products that are easier to transport by road. This is the main reason why Poland overtook China to become Ukraine’s largest trading partner in 2022.

Exports fell in all sectors of the economy. The agri-food industry has been affected least of all (-15.5%). Foreign sales of metallurgical products dropped by up to 62%, and minerals by 49%. In 2021, these categories of goods accounted for 24% and 12% of exports respectively.

Ukrainian imports of almost all major commodities have also declined, with two exceptions that are directly linked to the war. The destruction of the country’s only refinery forced Kyiv to import more fuel from the EU. In turn, missile attacks on the power infrastructure have led to a surge in the import of power generators.

Chart 8. Comparison of exports and imports of goods in 2021 and 2022 for individual sectors

Source: State Customs Service of Ukraine.

IV. CHARACTERISTICS OF SPECIFIC SECTORS

1. Agriculture

This is a key branch of the Ukrainian economy as it generates over 10% of the country’s GDP. Up to 70% of agricultural land is cultivated by enterprises. Although some of them have plots of over 100,000 ha, the largest role is played by medium-sized companies cultivating an average of up to 2000 ha of land. Before the war, the ten largest agroholdings leased 9.2% of all arable land in Ukraine, and the fifty largest ones 16.1%.

1.1. Production

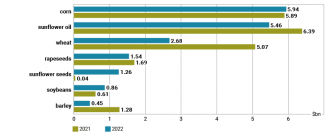

The Russian invasion led to a significant decline in agricultural production in terms of both cultivated area and harvest. Before the war, around 28 million ha of land were cultivated in Ukraine, but in 2022 this figure dropped to 23.4 million ha, half of which was used for growing grains and 8 million ha for oil plants. In 2022, 53.9 million tonnes of grain (-37.4% y/y) and 18.1 million tonnes of oilseed (-20.7% y/y) were harvested. The smaller harvests affected most of the country’s key agricultural produce (see Chart 9), in particular corn (-37.8%) and wheat (-35.5%), although in the case of oilseed the declines were smaller, and rapeseed harvest even increased.

Chart 9. Comparison of the key grain and oilseed harvests in 2021 and 2022

Source: State Statistics Service of Ukraine.

Declines in agricultural production varied depending on the geographic area. The regions where the front line runs or where fighting has been taking place have suffered the most, and the western part of the country has been affected the least, with some regions even seeing increases. However, it should be noted that agriculturally this is the least developed area.

Initial projections for 2023 predicted that the situation would continue to worsen. In August, the Ministry of Agricultural Policy and Food of Ukraine revised its forecasts due to better weather conditions. It is currently estimated that 56.6 million tonnes of grain and 20.3 million tonnes of oilseed will be harvested this year, which is about 5% more than in 2022.

Ukraine’s agricultural industry is very export-oriented. Before the outbreak of the full-scale war, it was estimated that the domestic consumption of wheat stood at 8 million tonnes and corn at 7 million tonnes, which is much less than the total harvest. Currently, domestic demand has decreased even more since several million of Ukraine’s residents have emigrated.

1.2. Exports

Before the Russian invasion, the sale of agri-food production was Ukraine’s main export: in 2021, it generated $27.7 billion, or nearly 41% of total exports, and contributed around 14% of the country’s GDP. Unprocessed or semi-processed products, such as grain (mainly corn and wheat), oilseed (mainly rapeseed) and oils (especially sunflower oil) accounted for the greater part of this sum ($21.3 billion). It is important to note that most of them (especially grain) were quite inexpensive relative to tonnage, which meant that the cost of logistics played a very important role in the profitability of sales. Before the full-scale war, food was mainly exported through the Black Sea ports; over 90% of production passed through them.

The war has led to a collapse in exports; in 2022 they shrank by 35%. In the case of agricultural products and food, the decline was much smaller (15.5%). In effect, there was a relative increase in exports of food: in 2022 it accounted for 52.9% of total exports, and in the first half of 2023 for 60.6%. As before 24 February 2022, the vast majority (79%) was accounted for by grains, oilseed and oils.

Source: State Customs Service of Ukraine.

Several factors have contributed to the relatively good results of sales of agricultural products. The so-called grain corridor, wherein three Ukrainian Black Sea ports could send food abroad, started operation in August 2022; in Q4 2022 and Q1 2023, it accounted for over 50% of exports in this category. In addition, the ports on the Danube (which had been virtually unused before the war) began to play an important role, and around 2 million tonnes of Ukrainian agricultural production per month passed through them last summer. In addition, so-called solidarity corridors were opened, enabling the sale of grain by land (a route almost unused before the war) to EU countries and in transit to EU ports. Additionally, in June 2022 the EU temporarily lifted tariffs on Ukrainian exports.

The solidarity corridors resulted in a massive inflow of grain and oilseed to Ukraine’s EU neighbours, which before the war had only imported them in small quantities. As a result, at the end of April this year Brussels banned Ukraine from selling wheat, corn, sunflower and rapeseed to four neighbouring countries (Poland, Slovakia, Romania and Hungary) and Bulgaria until 15 September. These are important markets: in 2022, the total value of exports of the above-mentioned products to these countries stood at €3.2 billion (including goods worth €960 million sold to Poland), which accounted for 46% of Ukraine’s sales to the EU, and in the first five months of 2023 it reached €884 million (nearly 28% of exports to the EU). For more detailed information on the trade in agricultural produce between Poland and Ukraine, see the Appendix.

2. The energy sector

Before the war, Ukraine had an extensive energy sector with well-developed electricity production industry (including nuclear power plants) and a growing share of renewable energy sources. It also used to be Europe’s fifth largest producer of natural gas. This made the energy sector one of the most important branches of the country’s economy.

2.1. The gas sector

Gas production in 2022 reached 18.5 bcm, a decrease of 7% compared to the previous year. The largest outputs of natural gas were achieved by UkrGasVydobuvannya (13.2 bcm, -3% y/y) and Ukrnafta (1 bcm, -7% y/y); these companies are part of the Naftogaz Group. The remaining share (4.3 bcm, -15% y/y) was produced by private enterprises.

Source: OGTSU.

The decline in production was primarily caused by the armed hostilities, which in 2022 were also seen in those parts of Kharkiv oblast where natural gas deposits are located, and in their immediate vicinity. Although the gas infrastructure, unlike the power supply grid, was not a target of regular mass missile attacks, it did come under attack on several occasions. Despite the difficult situation, investments aimed at increasing production have been continued: UkrGasVydobuvannya drilled 47 new wells in 2022.

According to preliminary data, gas consumption in 2022 fell to 20.1 bcm (a decrease of 25% y/y), the lowest level in the history of independent Ukraine. This happened because several million people had left the country, and industrial companies (especially heavy industry) had significantly limited their operations. No information on gas consumption by specific consumer groups has been provided.

Chart 12. Gas consumption and its dynamics in 2018–2022

Source: Naftogaz.

Gas imports in 2022 stood at 1.5 bcm (-42% y/y). Taking into account the decline in consumption and a relatively small reduction in own extraction, this means that the country was almost self-sufficient (92%) in terms of demand for this raw material.

Despite the hostilities, the transit of Russian gas through the territory of Ukraine was not discontinued, and its volume reached 20.4 bcmin 2022, the lowest since 1991 (in 2021, it was 41.6 bcm). Most of the gas was sent to Slovakia (16.5 bcm, -40% y/y) and to Moldova (2.5 bcm, -21% y/y). Some of the supplies went to Poland (1 bcm, -65% y/y) and Romania (400 mcm, -10% y/y), but deliveries to these countries were made only until May last year.

2.2. Fuels

Before Russia launched its full-scale invasion, Ukraine was only meeting about 50% of its own demand for gasoline, 15% for diesel oil and 20% for LPG. In 2021, up to 71% of imported fuel originated from Russia and Belarus, but these supplies were discontinued after 24 February 2022. The EU accounted for only 19% of imports, more than half of which were fuels from the refinery in Mažeikiai, Lithuania (owned by PKN Orlen). These were transported in transit through Belarus, which Minsk suspended a few weeks before the start of hostilities.

Moreover, the blockade of Ukrainian ports made the import of fuels by sea impossible, and the situation was further aggravated by intense missile attacks on fuel bases throughout the country and the destruction of the only operating refinery in Kremenchuk. This led to a deficit by the end of the first half of 2022. The crisis was averted by redirecting all available means of transport to import fuels from EU countries. Vehicles transporting these goods across the border were prioritised, and the Polish side allocated half of the road crossing in Dorohusk exclusively for the needs of fuel transport. Fuel was transported mainly through two corridors: from Poland directly, or transit via Poland and Romania. Ports on the River Danube were also used for this purpose, as was (periodically) the product pipeline from Hungary (for importing diesel oil).

As a result, the geographical structure of fuel imports has completely changed. Before the war, Ukraine imported only 21% of fuels from the EU, but in the first half of 2023 this share rose to 61%. The main non-EU suppliers are India and Turkey. In turn, Poland (680,000 tonnes in January-May this year) and Lithuania (283,000 tonnes in the same period) are the key suppliers among the EU member states; exports from these two countries account for over 50% of the EU’s fuel exports to Ukraine and almost a third of all fuel supplies to this country.

Chart 13. Imports of fuels from the EU to Ukraine in January–May 2023

Source: Eurostat.

2.3. Electricity

Before the Russian invasion, Ukraine had a well-balanced electricity production structure. About half of the country’s electricity (and up to 60% in some periods) was generated by nuclear power plants, around 30% by thermal power plants and heating plants, another 6–10% by hydroelectric power plants, and the rest by renewable energy sources (mainly solar and wind power plants). The country also had significant surpluses of installed capacity, which allowed it to export electric power to some of its neighbouring countries (Slovakia, Hungary, Romania and Poland).

The war has had a very serious impact on the functioning of Ukraine’s power grid. The part of the country occupied by Russia accounts for around 25% (around 15.5 GW) of the installed capacity of all power plants in Ukraine. The Zaporizhzhia Nuclear Power Plant (ZNPP), which is the largest facility of this type in Europe (6 GW of installed capacity), is of particular importance. Although the country has three other nuclear power plants, the ZNPP accounted for 43.5% of the capacity of Ukraine’s reactors. There are also numerous other conventional power plants in the territories controlled by Russian troops, including the Kakhovka Hydroelectric Power Plant, which was blown up by the invaders in June this year.

Regardless of the hostilities, the Ukrainian grid was connected to the Continental Europe Synchronous Area (CESA) in March 2022, and Ukraine had the capacity to export electricity from June to October last year. In October, Russia started regular massive shelling of Ukrainian power plants and power grid using ballistic missiles and kamikaze drones. These attacks lasted until March 2023, when the heating season ended. Although they did not cause a permanent blackout across the country, the network’s operation was seriously destabilised several times, and power outages (emergency and planned, usually lasting many hours) became everyday occurrences in almost all regions. The government did not provide details of the damage inflicted, but all power plants except nuclear ones were attacked, often repeatedly, and up to 50% of the power infrastructure was damaged.

In April this year the situation seemed to have stabilised; Ukraine even resumed exporting small amounts of electricity to Poland, Moldova and Slovakia. However, it was suspended again in June due to growing domestic demand related to higher consumption in the summer months, as well as the need to renovate the power plants. In May, Kyiv started importing electricity again (mainly from Slovakia, but also small amounts from Poland). It also had to ask for emergency help more and more frequently: in August this year it did so for three days in a row.

The restart in May this year of the 400 kV line between Rzeszów and the Khmelnytskyi Nuclear Power Plant, which had not been used since 1993, is immensely important in the context of cooperation with Poland. This infrastructure enables emergency supplies of electricity from Poland to Ukraine, and once the hostilities end it could be used to transfer the cheap electricity which Ukraine produced in large excess in peacetime.

3. Metallurgy

Ukraine has a well-developed metallurgical industry, a legacy from the Soviet period; iron ore was also mined at a high level. At the turn of the millennium, the most profitable assets of the sector were privatised and ended up in the hands of oligarchs (Rinat Akhmetov, Viktor Pinchuk, Kostyantyn Zhevago and Ihor Kolomoyskyi) and foreign capital (ArcelorMittal bought the country’s largest metallurgical plant in Kryvyi Rih). The largest metallurgical plants were located in the east, mainly in Donetsk, Dnipropetrovsk and Zaporizhzhia oblasts.

Before the war, Ukraine was a major producer of cast iron and steel. In 2021, it was the world’s 14th largest producer of these metals, with a share of 1.1%. Iron ore extraction in 2021 stood at 81 million tonnes (3.1% of global production), making Ukraine the world’s sixth largest producer. As with the agricultural sector, metallurgical production and ore mining were largely export-oriented. Foreign sales took place largely through ports on the Black Sea and the Sea of Azov (c. 70%), but the reliance on them was not as high as in the case of food exports.

Chart 14. Ukraine’s cast iron and steel production and its share in global production in 2013–2022

Source: Ekonomichna Pravda.

The metallurgical sector has suffered much more than other industries as a result of the war. The breakdown in production was mainly due to the blockade of the seaports; this limited sales significantly, forcing part of the production capacity to shut down, and obliging exports to be redirected via land routes across the borders with the EU. The regular power supply interruptions which were seen throughout virtually the entire country from October 2022 to March 2023, causing interruptions in the production cycle, were an additional problem.

Metinvest, owned by Ukraine’s richest oligarch Rinat Akhmetov, has suffered especially as a result of the direct military operations: its two metallurgical plants located in Mariupol were destroyed, and the companies which make up the holding sustained a total loss of $2.2 billion in 2022 (for comparison, a year earlier they had made a total profit of $4.7 billion). Metinvest’s cast iron production last year shrank by 72%, and steel production by 69%. The companies controlled by Viktor Pinchuk are in a slightly better situation as they are located in Dnipropetrovsk oblast, which is further from the front line. For their part the steelworks in Kryvyi Rih, which is part of ArcelorMittal, incurred losses of around $1.3 billion in 2022.

As a result, the value of exports of metallurgical products fell by 62.4% in 2022 (from $16 billion in 2021 to $6 billion), and their share in total foreign sales fell from 23.5% in 2021 to 13.6% a year later. The collapse in exports of metallurgical products and iron ore affected the countries that received them by sea, especially China, Turkey and the US, while sales to countries receiving them by land, such as Poland, the Czech Republic, Slovakia and Austria, remained at a similar level as in the pre-invasion period. Trade results for the first half of 2023 confirm that this trend is ongoing; almost all exports are directed to Europe. At the same time, it is worth noting that no significant increase in foreign sales of this group of goods can be expected as long as the blockade of the ports continues.

Chart 15. Comparison of cast iron & steel and iron ore exports in 2021 and 2022

Source: State Customs Service of Ukraine.

4. The IT sector

The IT sector is the only major branch of the Ukrainian economy that has not only not shrunk since Russia launched its full-scale invasion, but has actually grown in terms of both absolute values and share in GDP and exports. In 2022, income from foreign sales of IT services rose by $400 million (+5.8%) compared to pre-war 2021, to $7.35 billion. At that time, the industry accounted for almost half of services exports and around 4.5% of GDP.

However, the sector saw a 16% decrease y/y in Q1 this year. This is most likely due to a very high benchmark, since export revenues hit record highs ($2 billion) in Q1 2022, as well as the end of the global boom in ICT technologies caused by the COVID-19 pandemic. However, the industry is expected to stabilise rather than collapse in the coming years.

Chart 16. Exports of the Ukrainian IT sector’s services in 2018–2022

Source: Vox Ukraine on the basis of NBU data.

Ukraine’s tech sector has been growing steadily since 2012, when IT production was statutorily exempt from VAT for 10 years. The market for Ukrainian start-ups was already rapidly developing; one of its greatest successes was Grammarly, the software used worldwide for checking language correctness developed by three Ukrainian programmers back in 2009. Tax reliefs gave the industry an additional boost: thanks to them it could grow dynamically and expand into becoming a major branch of the economy, attract investors & foreign contractors, and reach outside the domestic market. Currently, Ukraine’s largest IT companies, such as Eram, SoftServe and GlobalLogic, have agencies not only in Western Europe, but also in Asia and South America, and each of them employs several thousand people (Eram over 10,000).

The Ukrainian IT sector employs around 300,000 people. It is characterised by high employment flexibility (most lower-level programmers are self-employed), a low average age of employees and relatively high average earnings, around 60,000 hryvnias per month (this is three times more than the national average of 20,000 hryvnias, or around $540). Before the war, the most important IT centres were located in large cities throughout the country which had technical universities boasting high levels of teaching mathematics, statistics and computer science; this ensured a constant supply of new, educated workers into the labour market.

Since Volodymyr Zelensky’s government took power in 2019, IT, which offers digital technologies and internet solutions, has been recognised as one of the Ukrainian economy’s key sectors. This stemmed from the desire to fulfil an important election promise of “[putting] the state in a smartphone”. The idea is to transfer state administrative services online in order to reduce corruption and close the tax gap. To this end, a special position of Deputy Prime Minister and Minister of Digital Transformation was created and has been held since August 2019 by Mykhailo Fedorov, the youngest minister in the country’s history. Fedorov is an effective manager and supporter of digital solutions, as well as the originator of the Diia e-governance website, which has turned out to be a great success.

Since February 2022, IT has enjoyed other privileges that were developed under Fedorov’s supervision, and which came into force a few weeks before the Russian invasion. These preferences are included in the package of tax reliefs and special legal regulations for the sector known as Diia.City. The VAT exemption expired on 1 January this year, and the government chose not to extend it despite appeals from entrepreneurs. It argued that tax revenues had to be increased (according to estimates, this move will generate around $100 million in taxes per year) and allocated for the needs of the war, that legislation had to be adapted to EU standards, and that the requirements of the donors had to be met; one of these came from the International Monetary Fund, which expects Ukraine to reduce as many tax breaks as possible.

Some companies from the tech sector have moved their offices to safer locations in the central, and above all the western part of the country as a result of the war. In this way they wanted to protect their employees while at the same time guaranteeing themselves uninterrupted access to the electricity, mobile and Internet communications necessary to continue work; that was particularly challenging given the Russian missile attacks on critical infrastructure. The enterprises quickly responded to these challenges by investing in alternative sources of electricity (generators) and communication (Starlink), as well as in employee safety and relocation packages, thanks to which they managed to retain their contractors and orders, as proven by the positive dynamics of the sector during 2022.

Companies and employees have also been relocated abroad. Within a year of the outbreak of the war, 17–21% of the sector’s employees (around 50,000 people, mainly women), had reportedly left Ukraine. According to surveys conducted by IT Ukraine Association, over 70% of enterprises have carried out unplanned relocations, mainly to European countries including Poland. Yalantis, Creatio, Plarium, Forte Group and other companies opened branches in Polish cities during 2022.

5. The defence industry

The Ukrainian defence industry has been almost completely destroyed as a result of the war. The state-owned company Ukroboronprom, which brings together most of the sector’s plants, estimated its losses at $3.4 billion (the losses of the country’s industry as a whole are estimated at $13 billion). The hostilities and the occupation of parts of the most industrialised regions, where the largest enterprises inherited from the Soviet Union are located, have had an especially strong impact.

Even before 24 February 2022, Ukroboronprom was preparing to transfer part of its operations (especially those that would enable it to maintain its maintenance & repair capabilities and to continue research & development) to the so-called safe areas, especially in the western part of the country. However, they also became the target of Russian attacks there. As a result, within a few weeks Kyiv lost most of its pre-war competences in the field of manufacturing, maintenance and repair of weapons, military equipment and ammunition.

Due to the war, Ukraine has been forced to change its remaining armament potential and focus it on the current needs of the fighting troops. Ukraine’s external partners also enabled the defence industry to continue working outside the country. In November 2022, then defence minister Oleksii Reznikov announced the creation of a three-level system for the maintenance and repair of weapons and military equipment. The first level includes maintenance and simple repairs organised at the level of military units; the second one covers medium-complexity repairs carried out in the country; and the third level covers comprehensive overhauls with the replacement of components, carried out in Poland, the Czech Republic and Slovakia.

In November 2022, Reznikov announced that Ukroboronprom, in cooperation with foreign partners, would begin producing post-Soviet 122-mm and 152-mm artillery ammunition and 120-mm mortar grenades. At the same time, the company started signing agreements with its counterparts from Poland, the Czech Republic and Slovakia on establishing joint ventures in ‘safe places’. Most often, this involves providing Ukrainians with access to production lines in plants in these countries or launching additional lines for their needs. In addition to ammunition, the agreements concerned the establishment of joint repair centres for post-Soviet weapons and military equipment.

Ammunition production began in February–March 2023, and part of the production and final assembly was located in Ukraine (this element is relatively independent as regards production of mortar grenades). In addition to the types of ammunition specified above, co-production also covered 125-mm tank shells; in April, Ukroboronprom signed a relevant agreement with the Polish-based Polska Grupa Zbrojeniowa. It should be noted that no artillery ammunition was produced in Ukraine during the Soviet period, and the first attempts to produce it were undertaken just before the war (work on developing production had started after 2014). According to the minister for strategic industries Oleksandr Kamyshin, Ukraine’s cooperation with its foreign partners enabled it to manufacture more than twice as much artillery ammunition in July this year as it had done throughout 2022.

Despite Ukroboronprom’s efforts, the government in Kyiv concluded that the company in its existing form was unable to successfully address the challenges linked to the construction of a modern military-industrial complex, that a more effective management model should be introduced, and conditions to attract foreign investments should be created. In March 2023, as part of the company’s reorganisation, the state-owned joint-stock company Ukrainian Defence Industry was established. On this occasion Prime Minister Denys Shmyhal announced that Ukroboronprom consisted of 137 entities, including 21 located in the occupied territories. Ukroboronprom was liquidated on 28 June, and its assets were taken over by the Ukrainian Defence Industry. The company’s management also inherited three tasks which its predecessor had still not fulfilled: increasing arms production, curbing corruption in the defence sector, and finishing the reform of the defence industry.

As a result of these transformations, contacts with foreign partners were intensified, and Ukraine started making attempts to interest Western companies, especially those from the US, the UK, Germany and Sweden, in investing in its defence sector. In May this year the management of Germany’s Rheinmetall announced its intention to organise the production of tanks (ultimately, the new plants would produce up to 400 Panther vehicles per year), air defence systems and ammunition in Ukraine. In July, the company’s CEO announced that the first plant tasked with repairing Western weapons, including tanks and armoured personnel carriers, would be opened in western Ukraine within the next two to three months. Turkey’s Baykar has kept its promise to launch drone production plants in Ukraine; talks to this effect had already begun before the war.

Kyiv is trying to continue some of its own projects, of which the so-called missile programme is arguably the most important. Serial production of the Ukrainian Sapsan/Grom-2 ballistic missile was to be implemented by May this year as part of this programme, which would have made it possible to attack military infrastructure deep inside Russian territory. The continuation of the programme was facilitated by the fact that before 24 February 2022, its financier Saudi Arabia took over that part of the staff which had been responsible for it, as well as the documentation and prototypes, so they were not destroyed by the Russians. However, Ukraine’s capabilities allow it to produce only single Grom-2 units; meanwhile the missile programme turned out to be a failure and led to the dismissal of the management of Ukroboronprom, which was subsequently liquidated.

A more successful project is the construction of the Ukrainian 155-mm (NATO) howitzer on the Bohdana wheeled chassis. The first publications confirming the production of howitzers, most likely in Slovakia, appeared in May this year; previously, the only functional prototype had had to take part in the hostilities. Stugna-P anti-tank guided missiles are still being produced abroad; according to Minister Kamyshin, between January and July this year their production quadrupled.

Given the needs of the Ukrainian army, as well as the relative simplicity of their production, the manufacture of small drones in Ukraine has increased tenfold, according to Prime Minister Shmyhal. It should be emphasised that these are made from imported components by over 40 companies, mostly private (there were only 12 such companies before the war). According to the Ministry of Defence, these companies have provided the army with “thousands” of unmanned aerial vehicles of 28 types (the contracts provide for serial production of 10 types). This year, the Ukrainian government reportedly allocated nearly $1.1 billion to the production of drones, and also abolished customs barriers affecting the import of components for them.

The private sector is also playing an increasingly important role in the production of ammunition components. The number of suppliers of 82-mm and 120-mm mortar grenade shells increased from two in February this year to 14 and 13 respectively in August. According to Minister Kamyshin, the state’s share in the defence industry has decreased significantly (before the war, it was 80%), and is planned to drop to only 20% over the next five years.

V. TRANSPORT: OPPORTUNITIES AND RISKS FOR POLAND AND THE EU

The network of transport connections will have a strong impact on Ukraine’s economic relations with Poland, and will be a major precondition for the development of trade between Kyiv and Western Europe. The routes running through Poland will essentially allow Ukrainian companies to be included in the supply chains of European corporations and supply their goods to the Western markets.

Since it is uncertain whether Ukraine will regain the ability to transport goods via the Black Sea, Polish ports may become an important channel for dispatching Ukrainian goods to global markets. The Ukrainian government is already taking steps to quickly expand the country’s infrastructure connections with Poland. However, if these moves are made without consulting Poland and fail to take its interests into account, they will most likely become a source of tension and disputes in the future.

Enhanced infrastructural integration with Ukraine offers Poland an opportunity to benefit from participating in its reconstruction. Polish companies will most likely not have the organisational and financial potential needed to become leaders of the largest projects in this process, but they can undoubtedly participate in it as shareholders and subcontractors.

Given its favourable geographical location, Poland may also become a supply and logistics hub for Ukraine. An efficient network of connections would contribute to intensifying trade and capital flows, especially between southern Poland and western & central Ukraine, which would lead to the development of strong industrial ties. If the infrastructure is adapted appropriately, this will facilitate the deliveries of important components from Polish factories. In turn, Poland’s logistics industry stands a good chance of providing distribution and warehousing services to Western European enterprises in both countries, which will offer it higher margins. To achieve this, Polish companies must gain the opportunity to expand the network of transhipment centres in Ukraine, and to acquire shares in terminals already existing there.

If Poland and Ukraine decide to expand the transport corridor from Ukraine to Gdańsk for the transit of Ukrainian goods, then developing a system of transport subsidies financed from EU funds may prove beneficial. The Polish-Ukrainian cross-border infrastructure should also ensure the effective movement of goods between factories located in Germany, Central Europe and Ukraine. Most likely, the automotive industry will be one of the first to invest on a larger scale in Ukraine (especially in its western regions). This trend was already apparent before the Russian invasion when the first factories were created there, primarily those manufacturing wire harnesses for automotive production. By including Ukraine in the Central European industrial cluster, the Polish logistics sector will be able to handle these streams in the future and thus contribute to reforming the Ukrainian economy so that its model is no longer resource-based.

However promising the opportunities linked to transport cooperation may seem, some serious risks should also be considered. Poland will find it challenging to develop transport ties that will ensure the efficient flow of goods across the border which will be necessary for the reconstruction and reform of Ukraine, while at the same time guaranteeing equal rules of competition for Polish and Ukrainian companies on the EU market. Ukrainian companies, which have been cut off by Russia from the transport route via the Black Sea, will strive to expand into the EU. The Ukrainian side must realise that the prolonged war cannot be used as an excuse for it to be given privileges available to member states before its accession to the EU and without implementing the relevant reforms. Unless the EU obliges Ukrainian firms to comply with European standards in the field of production (for example, social or phytosanitary standards) or services, they may gain unfair conditions for competing with Polish companies on the EU market (for example, in the field of agricultural products or logistics services). When it comes to transport, member states will certainly not agree to provide Ukrainian carriers with permanent and full access to the EU market if they are not obliged to meet environmental or social requirements similar to those that apply to EU companies (in accordance with the mobility package).

Another controversial area may be cross-border rail connections. Kyiv’s plans suggest that Ukraine may try to take advantage of the benefits offered by handling the transhipment of goods onto the tracks of the European network. As a result of the extension of the existing standard-gauge connections (used in Poland) to the vicinity of Lviv, Ukrainian enterprises will gain all the added value from reloading from broad-gauge and road transport onto rail networks. Ukraine has already established a company in Poland, UZ Cargo Polska, that will probably be tasked with gaining significant shares in the freight transport market. Experience from the pre-invasion period, especially when Ukraine blocked PKP LHS transport at the turn of 2022, shows that Ukraine may be planning assertive moves against Polish railway companies in order to defend its own interests.

VI. FORECASTS

1. Short- and medium-term perspectives (until the war’s end)

At present it is impossible to predict how long the armed conflict in Ukraine will last. However, it can be assumed that it will not end in the next few months. This means that the recently observed trends in the Ukrainian economy will continue. Even if the forecasts regarding GDP growth are confirmed, even in the best-case scenario it will not exceed 5%. It is an open question as to how severely the export results will be affected by the loss of the grain corridor, which used to be Ukraine’s main route for exporting its agricultural produce, but was closed by Russia in July this year.

One of the challenges is to maintain the current level of financial aid from the West, without which the Ukrainian state would not have been able to function. It can be said that foreign financing of budget expenditure for this year is largely guaranteed, but it is not known how the situation will change in the months and perhaps years to come. Therefore, the position of the US will have a great impact, as it is not only the most important weapons supplier, but also one of Kyiv’s main donors. There is a risk that during the campaign ahead of the presidential election – and especially later, if a Republican candidate wins – Washington may seriously limit its financial support for Ukraine.

Russia is likely to resume the mass shelling of Ukrainian electricity production and transmission infrastructure in the autumn, which will again cause long-lasting power outages throughout the country. There is also a risk (albeit apparently low) that Russia will start attacking nuclear power plants, something it has so far avoided. This would almost certainly result in blackouts across most of Ukraine. The gas transmission infrastructure may also come under attack; this could destabilise or even paralyse the heat production system, and thus have very serious consequences for city residents during the heating season.

The metallurgical sector will not increase production as long as the ports in the Black Sea are blocked. Ukraine can only regain the status of a major producer of steel products and iron ore if it can use the ports. However, it seems doubtful that it will resume its status as a large exporter of such goods because it would have to rebuild both of the destroyed steelworks in Mariupol in order to bring exports of metallurgical products back up to the pre-war level. Even if Ukraine manages to liberate the city, it will probably not be able to implement such large investments in an area so close to the Russian border.

Other disasters caused by hostilities that are now difficult to predict, such as the destruction of the Kakhovka Dam by Russian troops in June this year, cannot be ruled out. The side effects of that attack included problems ensuring access to water for agriculture in the region, as well as for residents and industry in Kryvyi Rih, Nikopol and other cities.

The IT sector will remain one of the major driving forces of the Ukrainian economy. However, the current rapid growth rate (around 20% y/y) will probably slow down in the coming months, as indicated by the data for Q1 of this year. Although the industry has adapted quickly to war conditions, foreign contractors are concerned that Ukrainian companies may not be able to complete their orders. Other problems include the outflow of workers, the higher costs of retaining current employees and hiring new ones, investment risk, expensive loans, and potential technical problems such as interruptions in access to the IT network and electricity due to Russian attacks. The Ukrainian IT sector will also be influenced by global trends, such as the falling demand for communication technologies after the end of the COVID-19 pandemic and the development of artificial intelligence.

The current situation of the Ukrainian defence industry cannot be used as a reference point. Before the war, it used to produce armour, transport aircraft and a broad spectrum of missiles (from man-portable guided missiles to intercontinental ballistic missiles). It has been destroyed in this form, and the remaining resources have been focused on current deliveries of ammunition and maintenance and repair of equipment. However, the sector is unable to carry out even these basic tasks on its own, and its production accounts for a small share of the supplies necessary for the army. If external cooperation was discontinued, the Ukrainian defence industry would in fact cease to exist, as it would not be able to offer any product on its own (those currently produced require both production capacity and components outsourced from foreign partners).

2. Long-term perspectives (after the war)

It is difficult to predict how long the Russian-Ukrainian war will last, and it is even more difficult to predict how it will end. At present, the goal Kyiv has set for itself – the liberation of all the enemy-occupied territories, including Crimea – seems unrealistic. At this stage, an agreement that would bring lasting peace is equally unlikely. Although the Ukrainian government and the vast majority of public opinion are opposed to any compromise with Moscow, it is possible that the prolonging conflict, the growing number of dead and injured, increasing material losses and growing fatigue will cause the public mood to change.

If there is a ceasefire rather than a lasting peace, no massive inflow of foreign investments should be expected, especially in areas located close to the Russian border or the front line – an area which in fact encompasses almost half the country. The Western and central regions will develop faster. The viability of rebuilding cities that have been completely destroyed as a result of hostilities, such as Bakhmut or Severodonetsk (if they are liberated) remains an open question. A similar dilemma concerning many industrial facilities will arise; most of them were built in Soviet times, and were already outdated before the war.

The unblocking of the Black Sea ports will be crucial for the Ukrainian economy. At present, they are mostly under discussion due to the question of grain imports & exports, but before the war, they were a key export route through which about two-thirds of Ukrainian goods were exported, including such important ones as agricultural and metallurgical products. Unblocking them would enable not only an increase in food sales, but also exports of other goods, thanks to which industrial plants (especially in the steel industry) would be able to resume operations.

Another unresolved issue is how to finance the reconstruction of Ukraine. Even though more than a year has passed since the conference in Lugano, during which a plan for this project was presented (Kyiv estimated the needs at $750 billion), it is still unclear where the funds will come from. Even if we assume that Ukrainian damage estimates are overrated, this process will still cost hundreds of billions of dollars. The proposals presented so far by international financial institutions, such as the World Bank, EBRD and EIB, as well as the Ukraine Facility instrument proposed by the European Commission, are aimed at covering the country’s current needs quickly, and not at the fundamental reconstruction or even construction of new infrastructure and industrial facilities that would enable Ukraine to move onto the path of rapid economic growth.

At the moment the chances of claiming reparations from Russia are practically zero, because it seems extremely unlikely that Moscow would agree to pay Kyiv any compensation without suffering a devastating war defeat. Recently, it has been suggested more and more often that the frozen assets of the Central Bank of Russia (around $300 billion) and funds owned by Russians who are subject to sanctions should be transferred to Ukraine. Theoretically, this move is possible. However, Western countries would have to take the appropriate political decisions and then coordinate their efforts to develop and implement new legal mechanisms. Although this topic has been discussed since spring 2022, no visible progress has yet been made.

Ukraine has an opportunity to develop new branches in the energy sector as part of the European Green Deal. It may become a major producer of biomethane; according to various estimates, its annual output may reach 10–22 bcm, which could cover 10–20% of the EU’s demand for this gas. In a much longer perspective, Ukraine has the opportunity to transform into an important producer and exporter of green hydrogen; it was even indicated as a priority partner country in the European Hydrogen Strategy. However, Ukrainian projects in this area are at a very early stage, and a qualitative leap will require multi-billion investments.

When the war is over, the Ukrainian defence industry will be rebuilt from scratch, and will still depend on foreign support. Given the external competition and the highly probable shortage of its own funds for investments, Kyiv is unlikely to regain its position as a player on the international arms market in the foreseeable future. Ukraine’s standing may be slightly better if the conflict is frozen. Some of its supporters may then decide to move production to Ukraine in order to lift the burden off their own economies, but they will impose licensing restrictions on it and/or make Ukrainian industry dependent on supplies of components.

The worsening demographic crisis will strongly affect Ukraine’s economic development in the future. The demographic situation in Ukraine was very difficult even before the war. Since the country gained independence, the birth rate has been negative, and in 2021 the disproportion between the number of deaths and births reached nearly 450,000. As a result of the Russian invasion, several million citizens left the country (estimates are quite divergent, ranging between 4 and 8 million), around half of whom were minors. Although surveys conducted among refugees show that about two-thirds of them have declared a desire to return to Ukraine, experience from other war-torn countries shows that in reality much fewer people will do so, and the longer the conflict lasts, the more will settle abroad permanently. On top of this, when martial law ends, a certain number of men (difficult to estimate) who are currently prohibited from leaving the country will leave permanently to join their families, which means that a significant percentage of young people who are able to work will not join the reconstruction process.

There are many indications that Ukraine will start accession negotiations with the EU in the next few months. Although it will take a long time before Ukraine actually joins the EU (European Commission officials say 20–30 years), the process itself– combined with structural reforms to the state, especially reform of the judiciary – may create a positive business climate and an inflow of foreign investments. However, this will depend on how and when the war ends.

APPENDIX

Trade in agri-food products with Poland

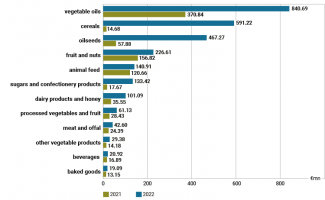

Before the Russian invasion, trade in agri-food products between Poland and Ukraine was largely balanced; depending on the year, the trade volume stood at €1.3–1.7 billion, and the values of imports and exports were similar. 2022 saw a dramatic rise in food imports from Ukraine, but it is worth noting that exports of this category of goods from Poland to Ukraine increased by 16.4%, even though several million refugees had fled the country.

Chart 17. Export of agri-food products from Poland to Ukraine and their import from Ukraine in 2019–2022

Source: Eurostat.

Although the media have focused on the surge in imports of Ukrainian grains and oilseeds, major increases have also been seen in other categories, primarily vegetable oils (mainly sunflower oil), confectionery products, poultry and dairy products. At the moment it is difficult to say whether the increase in imports of food other than cereals is permanent or temporary; sales of some goods (such as dairy products) dropped significantly in the first months of 2023, while sales of other goods (for example, poultry or animal feed) remain at a high level.

Chart 18. Main categories of food imported by Poland from Ukraine

Source: Eurostat.

Poland is also an important supplier of food to Ukraine and, unlike with imports, it mainly exports processed products with higher added value. In some categories very large increases can be observed; for example, sales of vegetables (mainly tomatoes and onions) rose by 109% in 2022, processed vegetables by 44%, and exports of processed meat almost quadrupled. It should be emphasised that the value of exports from Poland in the first months of 2023 was at a high level and will probably remain so, unless Kyiv decides to impose any restrictions on trade with Poland in response to the ban on the export of grain and oil plants to the four neighbouring countries and Bulgaria which has been in force since April.

Chart 19. Main categories of food exports from Poland to Ukraine

Source: Eurostat.