Between hope and illusion

Contents

I. LESSONS LEARNT FROM THE 2015 MIGRANT CRISIS

III. LEITKULTUR OR GERMAN ADAPTATION?

V. THE GOVERNMENT’S INSUFFICIENT RESPONSE

VI. CONCLUSIONS: NO PROSPECTS FOR CHANGE

1. Migrants’ incentives to select Germany as their destination

3. Immigration as an opportunity

INTRODUCTION

The surge in asylum applications in a situation when the state is taking care of more than 800,000 refugees from Ukraine has led to a multi-faceted crisis in Germany. Like the previous migration crisis in 2015, disputes between the federal states and the federation over funding have arisen, and the local authorities responsible for providing shelter and care to asylum seekers do not have enough places for them. However, the much more serious challenge to Germany’s political elite involves the loss of the public’s confidence in the state, combined with a prevailing conviction that the government has lost control of migration policy in its broadest sense. The fact that Germany’s leaders are constantly making demands of their citizens, combined with the immigrants’ insufficient integration into German society, have triggered public resistance. As a consequence, support for the anti-immigrant Alternative for Germany (Alternative für Deutschland, AfD) party has been on the rise. At present, the AfD is the second most popular party after the Christian Democrats in polls conducted at the federal level, and it is now the most popular party in the eastern federal states, where its level of support is running at over 30%. The mounting economic crisis may further exacerbate the situation, and if this happens the authorities will face problems regarding the distribution of wealth and resources to citizens and asylum seekers.

The government of Chancellor Olaf Scholz has launched a belated and rhetorically harsh offensive aimed at curbing illegal immigration. However, the measures taken are too conservative and will not result in any breakthrough in Germany’s asylum policy in the short term, as this would require all parties to agree on profound changes to the relevant legislation at both the German and the EU level. Moreover, a series of international agreements would need to be concluded following the negotiation process. Alongside this, Berlin is aware that the biggest challenge Germany will face in the coming decades is its ageing population and a major shortfall of labour. Without economic migrants, Germany will be unable to maintain its current standard of living and its economic growth rate.

MAIN POINTS

- Germany has recently seen the biggest inflow of refugees since the 2015–16 crisis. In 2023 more than 300,000 asylum applications were submitted, 60% more than the figure for 2022. The combination of such a large number of asylum seekers with more than 800,000 refugees from Ukraine who arrived in Germany following the Russian invasion has resulted in the resources of both state and society becoming exhausted. Germany’s attractiveness as a destination for refugees results both from the generous social welfare benefits these individuals receive while their applications for protection are being considered, and from the fact that Germany is already home to numerous immigrant communities. Another important factor involves the conviction that Germany’s legislation and judicature are favourable to refugees, which effectively guarantees them the right to stay in Germany even if their asylum applications are rejected.

- The problems linked with refugees mainly affect the local governments which, in accordance with German law, have the responsibility for taking them in and giving them shelter. The competence of the local government also includes providing them with initial integration assistance at schools and special integration courses. The cost of the migration policy, which is more than €30 billion annually and is in large part funded from the local budgets, is posing an increasing challenge. A dispute between the federal states and the federation is ongoing regarding a more balanced distribution of these funds. The boost provided to those institutions which deal with migration as a result of the lessons learnt from the migrant crisis of 2015–16 – including the Federal Office for Migration and Refugees (BAMF), which is responsible for processing the applications, as well as schools – has also proved insufficient. The continuous inflow of immigrants is exhausting the number of places available in refugee centres, overcrowding in schools and a collapse of the housing market.

- The migrant crisis has triggered tensions within society and resulted in the transplantation of various ethnic conflicts into Germany. One of the most serious such conflicts involves Turkey and the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK), a conflict which has now also arisen within the Turkish diaspora in Germany, which numbers more than 3 million individuals. The German secret services have repeatedly issued warnings about the influence of Turkish intelligence structures, including repression targeting Turkish oppositionists. Tension following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in 2022 also became evident. The Russian minority residing in Germany organised numerous rallies to express support for the invaders, and to protest against the provision of help to Kyiv. Another problem involves anti-Semitism, which has spread in some Muslim communities. One consequence of such conflicts is problems with teaching and managing ethnically-motivated disputes in schools, which highlight the growing proportion of pupils with a migrant background and contribute to the emergence of increasing linguistic and cultural barriers between them and the German population.

- The conviction that the state is shouldering an excessive burden and lacks the necessary agency to deal with these issues has undermined the German public’s confidence in Chancellor Scholz’s government. Most Germans believe that the ruling SPD–Green–FDP coalition is unable to tackle the problem of managing migration or to mitigate the consequences of the recent crisis for German society, and that immigration is generating more costs than benefits. Alongside this, Germans are becoming increasingly supportive of plans to toughen the legislation, including to set an upper limit on the number of immigrants who are granted asylum. The fact that politicians are not interested in tackling the specific problems which have resulted from taking in an excessive number of immigrants has boosted critical attitudes towards them, and sparked questions regarding the criteria for accepting new incomers.

- Germany’s stance on migration is one of the most important, and at the same time most controversial, issues in the country. The extremist parties, such as the AfD and the new project promoted by Sahra Wagenknecht, have so far been most critical of it. Some of their potential voters see asylum seekers as a threat, and have demanded that a total ban on helping them should be introduced alongside a radical shift in migration policy. Another group of citizens supports economic migration because it is aware that, due to an aging population and a shortfall of around 400,000 workers annually, Germany will be unable to maintain its present standard of living without this type of migration. At the same time, this group of German citizens favours the plan to curb the practice of granting asylum, and has emphasised the importance of Germany’s Leitkultur (for more on which see section III). There are increasingly frequent suggestions that in exchange for the social welfare benefits they receive, new immigrants should become involved in actions carried out by local communities, which is expected to accelerate their integration into German society. Some German citizens, mainly the better educated who live in big cities, still argue that Germans should remain open to refugees and should adjust themselves to the challenges posed by migration; for example, they should be ready to share the state’s public resources with them. Proponents of a liberal attitude towards migration argue that instead of curbing it, efforts should be boosted to integrate the refugees into society. The dispute over what narratives should be applied in this respect will be exacerbated when further groups of immigrants arrive in Germany and problems as to how to overcome the emerging difficulties begin to mount, especially in the context of Germany’s ongoing economic crisis.

- These shifts in public sentiment combined with the pressure from increasing migration have forced the federal government to go onto the political offensive. By the end of its term, the Scholz government intends to take a number of measures to curb the inflow of refugees. The main emphasis has been placed on domestic issues, including the plan to continue to perform border checks, to eliminate immigration incentives by changing the form of the welfare benefits offered to immigrants from cash to payment cards, to accelerate asylum procedures, and to introduce facilitations for asylum seekers intending to take up employment. However, a dispute is ongoing within the government regarding the scope of the modifications. The FDP supports the aforementioned proposals, while their fellow coalition members the Greens are clearly split over this issue. This party is facing a dilemma: on the one hand, most Germans and selected local government officials representing the Greens are demanding that the policy should be toughened, while on the other such a move could lose them the support of their more left-wing voters. Even if the Greens agree to toughen the state’s migration policy, it will require much more profound reforms to achieve a permanent reduction in the number of asylum applications than those proposed by the government. It will be necessary to amend those provisions of the constitution which concern the right to asylum, and to sign agreements with other EU member states and the refugees’ countries of origin.

- The AfD has been the biggest beneficiary of the recent crisis. Its level of support has risen due to its radical opposition to the current migration policy. At present, according to polls, the AfD is Germany’s second most popular party (after the CDU). The present crisis, just like the one that emerged in 2015, has given this party an opportunity to continue to improve its standing in polls. In particular, support for the AfD has been on the rise in eastern federal states, where it is the most popular party. The 2024 electoral timetable is especially favourable to it because it includes elections to the European Parliament and, most importantly, to the Landtags of Saxony, Thuringia and Brandenburg. Migration policy will be the most important topic of the coming campaign, which may help the AfD to come first in the eastern federal states. The failure of the SPD–Green–FDP coalition’s asylum policy will influence the outcome of the elections to the Bundestag in 2025, and will once again strengthen the extremist parties.

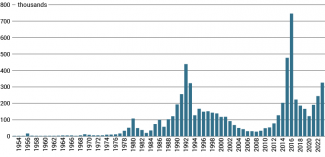

I. LESSONS LEARNT FROM THE 2015 MIGRANT CRISIS

5.6 million asylum applications have been submitted in Germany since 1990. In the period between January and November 2023, 304,000 individuals applied for asylum. This represents an increase of 60% compared with the corresponding period in 2022, when around 218,000 applications were submitted. In mid-2023, around 3.27 million registered asylum seekers and refugees with several different statuses as regards their residence status lived in Germany, including around 835,000 Ukrainians. 279,000 immigrants were obliged to leave Germany, although this figure also includes 225,000 who could not be deported for various reasons (mainly the lack of documents, or their country of origin refusing to accept them as its citizens).

Germany has been among Europe’s leading destinations for refugees. This results from the following factors:

- the conviction shared by migrants regarding Germany’s openness to refugees and its readiness to take in further groups (Willkomenskultur); the former Chancellor Angela Merkel made the ‘We can do it’ slogan (Wir schaffen das) one of Germany’s globally recognised features,[1]

- the country’s generous social welfare benefits, some of which are paid out in cash (see Appendix),

- the belief that an individual who arrives in Germany is allowed to stay there, an idea which is based on the peculiarities of the German law and its strict observance, as well as on the assumptions that the judicature is favourable to asylum seekers and that the deportation procedure invariably takes a long time to complete,

- the fact that numerous immigrant communities, such as those of Syrians, Afghans and Turks, already live in Germany, and

- the contradictory signals which the German authorities appear to send immigrants, for example encouraging economic migration (see Appendix).

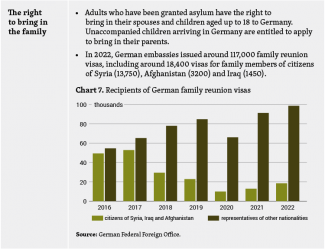

Chart 1. Number of asylum applications submitted in Germany since 1953

Source: Federal Office for Migration and Refugees (BAMF).

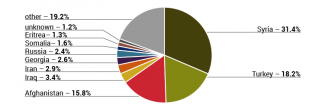

Chart 2. Countries of origin of individuals seeking asylum in Germany in the period between January and April 2023

Source: Federal Office for Migration and Refugees (BAMF).

The most serious migrant crisis hit Germany in 2015 and 2016, when 1.22 million individuals arrived there. The challenges which emerged back then had to be shouldered in particular by the local- and state-level administrations which found themselves responsible for providing accommodation to the immigrants and integrating them into society, a process which also included enrolling their children at schools. This sudden inflow of refugees paralysed the operation of the office which issues asylum decisions (BAMF) and resulted in profound social divisions, which triggered an increase in the level of support for the anti-immigrant AfD party. As a consequence, the government under Chancellor Angela Merkel made an attempt to contain the situation. This involved:

- taking measures to toughen migration legislation,[2]

- the EU signing a migration agreement with Turkey in 2016, which resulted in a major decrease in the number of asylum applications submitted,[3]

- adjusting the infrastructure and the operation of the local administrations enabling them to take in the refugees,[4]

- improving the efficiency of the BAMF by expanding its staff (by three times, to around 8100 employees) and budget (from €250 million in 2015 to around €760 million in 2022); this enabled it to accelerate the asylum procedure, as the average duration of the processing of an asylum application was reduced from several years at the peak of the previous crisis to seven months now.

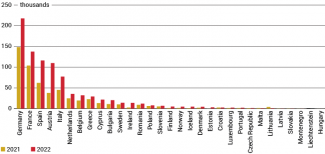

These decisions proved effective and enabled the state to adapt to the new circumstances. The situation changed again following the more recent inflows of asylum seekers and the decision to provide assistance to Ukrainians. The recent increase in the number of asylum seekers has resulted both from a surge in migration following the COVID-19 pandemic (in 2020 100,000 asylum applications were registered, while in 2021 the figure was 148,000) and from the constantly growing number of migrants who decide to settle in the EU. Between January and September 2023 around 179,000 individuals reached the EU via the Mediterranean Sea, around 60% more than in the corresponding period in 2022. In addition, migration pressure on the EU’s eastern border caused by the deliberate policies of the Russian and Belarusian government has increased.[5]

All these problems were exacerbated when around 1.1 million war refugees from Ukraine came to Germany (around 280,000 of them have since left the country). Their presence has been a major burden to the housing market and the education system. Around 214,000 children and teenagers from Ukraine are attending German general and vocational schools.[6] Germany classifies refugees into two categories: Ukrainians and others. Unlike asylum seekers, members of the former group are entitled to take up jobs immediately and, just like individuals who have been granted asylum, are eligible to receive full social welfare benefits rather than the reduced benefits offered to asylum seekers. Depending on a variety of factors, including their family status, each Ukrainian receives a so-called citizen’s allowance of €501, and Ukrainian parents receive an additional €250 for each child. Moreover, every Ukrainian refugee receives financial support to fund their accommodation. In the period from 24 February 2022 until the end of 2023, Germany spent around €13.4 billion on providing help to Ukrainian refugees nationwide, including around €6 billion in social welfare support offered to them and another €6 billion disbursed as part of subsidies for the local-level administration which took care of them.[7]

The large number of asylum seekers combined with the inflow of refugees from Ukraine have led to the gradual exhaustion of the state’s resources. This is particularly evident in insufficient access to flats and education (in Berlin alone there is a shortfall of 20,000 places in crèches) and the mounting financial crisis. This is combined with the integration problems faced by a large portion of migrants who have already resided in Germany for some time, and with unemployment affecting the new immigrants (see Appendix). The present situation is starting to resemble the one Germany faced during the most acute stage of the refugee crisis in 2015–16.

Chart 3. Number of asylum applications submitted by non-EU citizens in EU member states in 2021 and 2022

Source: Eurostat.

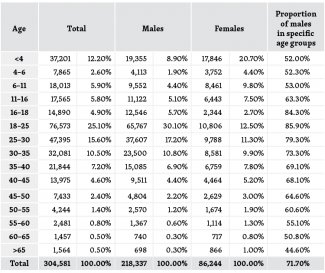

Table. Asylum applications submitted in Germany between January and October 2023 according to the applicant’s age and gender

Source: Federal Office for Migration and Refugees (BAMF).

At present, just like during the previous crisis, it is mainly the local communities that are forced to tackle the vast majority of the practical problems which have arisen. Once again, the overcrowding of refugee centres and the shortfall of flats for rent are resulting in price hikes and preventing the immigrants from finding accommodation, especially in big cities. The lack of flats also triggers social tensions in smaller towns which are being forced to take in increasing numbers of migrants, something which in turn sparks local protests. Rallies against immigrants who have been granted asylum and decided to settle in Germany are being organised nationwide, and not just in those eastern federal states which are less friendly to immigrants. The distrust of the authorities and the conflicts are intensified as public utility facilities, such as sports halls and schools, are rented to immigrants or transformed into migrant and refugee shelters.[8] The magnitude of the crisis is evidenced by the fact that the initiators of demonstrations and appeals to curb migration often include local representatives of the SPD and the Greens, that is the very same parties which until recently were advocating more liberal migration policy.

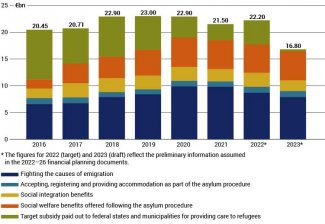

Both the general public and the local governments are increasingly criticising the expenditure on the broadly understood migration policy, on which Germany spends between €20 billion and €30 billion from its federal budget annually. This sum mainly includes funds aimed at combatting the causes of migration (a significant portion of these funds is spent on development cooperation, humanitarian assistance and support offered to states which are located on migration routes) and social welfare benefits paid out to asylum seekers in Germany. An increasingly intensive debate is ongoing on how to achieve a more balanced distribution of the costs between the federal states and the federation.[9] A large portion of this spending (around €16 billion) is still borne by the federal states and local governments, which are responsible for providing accommodation and other forms of assistance to asylum seekers. Another spending category includes funds earmarked for covering the social welfare benefits offered to Ukrainians and the increased cost of education provided to the new immigrants. As Germany’s economic and fiscal problems continue to mount, demands to curb spending on refugees (including those from Ukraine) have been increasingly frequent.

Chart 4. Germany’s federal level spending on refugee policy in 2016–2023

Source: Federal Ministry of Finance, after the Federal Agency for Civic Education (Bundeszentrale für politische Bildung, BpB).

III. LEITKULTUR OR GERMAN ADAPTATION?

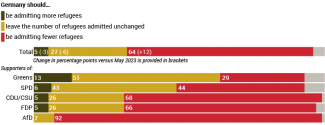

The conviction that the state is excessively burdened and lacks agency, combined with the immigrants’ failure to integrate and the street riots organised by newcomers themselves in German towns and cities, have sparked a shift in the German public’s attitude towards refugees. German citizens increasingly believe that immigration brings more costs than benefits (a recent poll gave that figure as 64%, the highest such number since 2015), and are demanding that the government curb the number of refugees the state decides to take in. This view is supported by up to 29% of the voters of the Greens and 44% of the SPD’s electorate, although these parties have always adopted a relatively liberal attitude towards migration. Almost 80% of Germans believe that the state is unable to pursue an effective migration policy, especially as regards accommodation, integration and the deportation of asylum seekers.

Moreover, 75% of German citizens believe that the basic problem involves the politicians’ failure to concern themselves with the specific challenges resulting from successive decisions to admit such large numbers of migrants. The border checks which have been in place since October 2023 on the border crossing points with Poland, the Czech Republic and Switzerland (and since 2015 on the border with Austria) are supported by the vast majority of Germans (82% of respondents) and most citizens are in favour of introducing limits on number of individuals who are granted asylum in Germany.[10] This has resulted in an increasingly intensive debate on the scope of the immigrants’ integration into society and provoked questions regarding the criteria for their acceptance. More and more German voters view refugees as a threat, and are demanding that the state stop providing them with assistance and undertake a radical shift in its policy in this respect. Supporters of the AfD are most sceptical about the asylum seekers; 95% of them believe that migration to Germany has a negative effect on their country. This view is shared by the supporters of the new party led by Sahra Wagenknecht. This stance is more popular in the eastern federal states than in the western ones.[11]

A more balanced attitude towards migrants is displayed by supporters of the opposition Christian Democrats and the co-ruling FDP, as well as a portion of the Social Democrats’ electorate. Although they support economic immigration (see Appendix), at the same time they favour a curb on the number of situations in which a migrant is entitled to seek asylum. They also demand that the refugees respect the German Leitkultur (leading culture). This term was coined by Prof. Bassam Tibi, a political scientist, who in the 1990s had written about the need for a social and political consensus based on European values. Friedrich Merz, the present leader of the CDU, introduced this term into the political debate. In 2000, as the head of the CDU/CSU parliamentary group in the Bundestag, he criticised the migration policy pursued by the SPD–Green government (multiculturalism) and contrasted it with Leitkultur, which he viewed as “a widely accepted definition of what we understand as our culture”.

The proponents of this model emphasise that all residents of Germany, including individuals who have been granted asylum, should respect the German constitution and the dignity of every human being. They also argue that not every culture enriches the host country, and they highlight the need to clearly define how the migrants are expected to behave, and that they should respect German law. They also emphasise the role of German culture in the migrants’ integration into society.[12] According to an increasing number of citizens, this process should be accelerated by applying the quid pro quo rule which states that individuals seeking asylum in Germany should perform community service for their hosts. Nationwide, Germans increasingly feel that a broad scope of assistance (including social welfare) should be offered to refugees in exchange for their involvement in serving the local community (such as assisting the staff of retirement homes).

Despite these difficulties, that portion of the German public which resides in big cities, is well educated and affluent continues to believe that Germany is a sufficiently large and rich state to be able to take in all individuals who seek asylum. Proponents of this view argue that while the refugees should respect the new rules, their hosts also should be open to change and willing to adjust to the immigrants.[13] This mainly involves their readiness to share public resources with the immigrants, including the utility buildings which have been made available to the asylum seekers instead of the local communities. Another proposal is to adjust the educational facilities to teaching children with a migrant background, rather than expecting foreign children who start attending German schools to speak fluent German.[14] According to the proponents of a more liberal migration policy, the problems resulting from the state taking in so many immigrants should be resolved in the first place by boosting the efforts made by both German citizens and representatives of the federal- and local-level administration, rather than by curbing migration. In addition, they believe that even if the government manages to temporarily curb the number of immigrants reaching Germany, in the long term the magnitude of the basic challenge posed by the need to take in climate refugees will not change.

Aside from calling for an increase of the relevant resources in Germany and for help to be provided to save and protect migrants on the EU’s border, radical supporters of the proposal to increase the number of situations in which individuals are entitled to seek asylum advocate changing the status of Ukrainian refugees so it becomes equal to that of other asylum seekers in Germany. Those Germans who support the proposal to ease the asylum policy are at the same time opposed to signing new agreements with African and Middle Eastern states (modelled on the agreement signed with Turkey) because it is impossible to guarantee respect for human rights and sufficiently high social standards in these countries. They are also opposed to deportations, and argue that these only affect the most vulnerable migrants who are easiest to detain. A particularly egregious example of these individuals’ attitude involves accusing people who advocate curbing the right to asylum in Germany of spreading far-right or even fascist views.

Increased tension over the issue of taking in refugees is also evident in more and more frequent instances involving attacks on their places of residence. In the first nine months of 2023, 1515 such incidents were recorded, more than the figure for 2022 as a whole (1371). The German police have attributed most of these incidents to far-right groups.[15]

Chart 5. The German public’s opinion on taking in refugees

Source: an ARD-DeutschlandTREND poll conducted by the Infratest dimap polling company, October 2023.

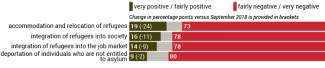

Chart 6. Assessment of the present refugee policy

Source: an ARD-DeutschlandTREND poll conducted by the Infratest dimap polling company, October 2023.

Germany’s internal security challenges are not limited to providing protection to the refugees staying in the country. Conflicts which the migrants have themselves transplanted to Germany have been causing increasing problems for the German law enforcement bodies. The most serious such conflicts include the dispute between Turkey and the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK), which Ankara views as a terrorist organisation, some aspects of which have become evident in Germany. As the fight between the PKK and Ankara intensifies, clashes between the supporters of both sides are taking place increasingly frequently across Germany, which is home to a Turkish diaspora of more than 3 million individuals. Moreover, at present Turkish citizens are the second largest group of asylum seekers in Germany. The German secret services have repeatedly warned against the activity and influence of the Turkish state’s intelligence body, known as MIT. This activity mainly involves attempts to manipulate the German public by spreading false information and targeting acts of repression against Turkish oppositionists residing in Germany.[16] In addition, Turkish politicians have organised intensive electoral campaigns in Germany, which not only divide the diaspora but also trigger rifts within the German political scene. This has resulted in demonstrations and sometimes even riots (such as the 2015 riots in Karlsruhe between supporters and opponents of President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan). Turkish politics has become an increasingly important topic for the Bundestag, as evidenced for example by tensions over the commemoration of the Armenian genocide conducted by the Ottoman Empire.

As a result of Germany’s decision to provide shelter to numerous refugees from Muslim states (since 2015 these have been the biggest group of asylum seekers; a total of around 5 million Muslims now live in Germany), the cultural and religious background and upbringing of some of these migrants have posed an increasing challenge to the state because they contradict democratic values. Another problem involves the anti-Semitic views which members of this group have expressed.[17] This was evident in October 2023, when in response to Hamas’s attack on Israel numerous demonstrations were held in Germany in support of Hamas; these were combined with various manifestations of anti-Semitism, and frequently led to clashes with the police. Recent years have also seen an increase in the number of assaults on law enforcement officers (including rescue workers and firefighters). This results, among other things, from the fact that some of the perpetrators of migrant backgrounds do not identify with the German state or its representatives.[18]

In this context, the importance of schools has increased significantly because they frequently are the first contact for immigrant children with the state, and as such they are one of the places which shapes those children’s attitudes towards the state. Education plays an exceptionally important part in creating and respecting the values, norms and ideas which conform to Germany’s official rules and goals. It creates opportunities to teach children about the state’s political structures, the rights and obligations of its citizens, and the country’s history and culture, which in turn helps to inspire the feeling of belonging to this country. German schools, which are generally overcrowded, underinvested, and most importantly insufficiently staffed, have problems offering the required quality of education and with dealing with ethnically-motivated conflicts. In the 2023 edition of the Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA), Germany recorded the worst score in its history, ranking 25th globally (for comparison, Poland ranked 15th).

Germany’s ongoing demographic shift has affected its educational performance, and an increasing proportion of pupils face language and cultural barriers. In 2022, the proportion of pupils with a migrant background rose to 26%, compared with 13% in 2012. In addition, these children frequently hail from families with a lower socio-economic status, which frequently determines their performance. Up to 42% of respondents with migrant backgrounds are in a difficult economic and social situation. This proportion is almost twice the average figure recorded for all pupils. Aside from that, almost two thirds of these children admitted that at home they speak a language other than German.[19]

The situation is particularly difficult in some schools in Berlin and several western federal states (for example North Rhine-Westphalia), where sometimes the majority of pupils in a given school come from immigrant families. In 44% of primary schools in Berlin, such children account for at least half of all pupils. In 27 such schools, at least 90% of the pupils are not native German speakers.[20] Aside from the structural problems and the insufficient quality of education, ethnically-motivated conflicts and manifestations of anti-Semitism represent further difficult issues. To assist teachers in addressing these challenges, the local governments have established special crisis centres (for example in Berlin). The problem is all the more serious because 40% of young Germans, including many individuals with a migrant background, have either never heard of the Holocaust or know ‘very little’ about it.[21] The new generation of immigrant pupils are much less invested in assuming responsibility for Germany’s Nazi past, while the textbooks from which they learn often discuss the issue of anti-Semitism in a selective or superficial manner.[22]

The support initiatives targeted at Ukrainian refugees since 2022 have also been accompanied by numerous tensions and threats, mainly from Germany’s Russian-speaking residents. This has been most evident during anti-Ukrainian rallies, one very specific manifestation of which was the motorcades driving through German cities (known as Autokorso).[23] The biggest such events were held in Berlin, Frankfurt am Main and Hanover, cities which are inhabited by large and well-organised Russian diasporas. In subsequent months most federal states banned the display of the letter ‘Z’ during these rallies, which had previously been widely used to express support for Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Fearing clashes, the authorities introduced a controversial ban on displaying Russian and Ukrainian flags during the anniversary celebrations of the end of the Second World War. In 2023, the ban on Ukrainian flags was lifted. Over that year pro-Russian rallies were held in numerous cities, during which their attendees expressed their criticism of German arms deliveries to Ukraine, and demanded that the sanctions be lifted and the Nord Stream 2 gas pipeline launched. These were frequently also met by counter-demonstrations. According to statistics compiled by the Federal Criminal Police Office (BKA), in the first eight months of the full-scale war more than 4000 crimes linked with it were recorded in Germany.[24]

V. THE GOVERNMENT’S INSUFFICIENT RESPONSE

German society’s increasingly restrictive/unwelcoming attitude towards immigrants, combined with the numerous challenges they pose, have forced the government to take action. Another element of this pressure involves the consistent failures of the ruling parties in the elections to several Landtags, as well as the growing popularity of the AfD, which mainly results from their criticism of the state’s migration policy.[25] However, a dispute has been ongoing within the government over the scope of the planned restrictions. While for the SPD and the FDP limiting the number of immigrants arriving in Germany is a pragmatic necessity which their own electorates favour, the Greens view this as an issue of major importance for the party’s identity, and argue that curbing the inflow of foreigners could undermine one of the party’s basic principles – and not for the first time in this parliamentary term, following the shift in the party’s stance on the export of weapons to conflict regions and the modification of its views on climate and energy policy, due to the crisis triggered by the war in Ukraine. During a media campaign launched in October 2023 which was intended to demonstrate that Chancellor Scholz had correctly interpreted the signals sent by the citizens and the local governments, he clearly indicated that too many immigrants without the right to stay in Germany were arriving there. The SPD leader also emphasised that further increases in irregular migration could pose a serious risk to Germany’s coherence and economic power.[26]

To stop this trend, several specific solutions need to be implemented. The ruling coalition intends to introduce them by the end of the Bundestag’s present term. Its proposed domestic policy measures include maintaining permanent border checks on selected state borders; reducing the number of factors which attract asylum seekers (see Appendix) to Germany, including obliging the federal states to offer assistance in the form of payment cards alone (with no option of transferring the money to a foreign bank account) or specific non-cash benefits; facilitating the procedure for individuals who have been granted asylum to be given employment; putting Georgia and Moldova on the list of safe origin states (to enable the more efficient processing of asylum applications and to accelerate the deportation procedure); and taking steps to increase the effectiveness of deportations. To achieve the latter goal, the state will need to boost the effectiveness of digitisation in public administration, increase the number of civil servants responsible for deporting illegal immigrants, and accelerate the relevant procedures.

These steps are to be supplemented by EU policy modifications, such as boosting the protection of the EU’s external borders and implementing an EU-wide solidarity mechanism which involves registering all immigrants arriving in the EU, so they can be distributed evenly among all the EU’s member states including Germany. In the most optimistic scenario, the SPD does not rule out a return to its 2004 proposal to process asylum applications outside the EU. The most important element of the plan, which has been endorsed by the Social Democrats, involves Germany signing agreements with the immigrants’ countries of origin to agree to take back individuals who have attempted to illegally migrate to Germany in exchange for Berlin consenting to legal economic migration. The Special Representative of the Federal Government for Migration Agreements Joachim Stamp (FDP; a former deputy minister-president of North Rhine-Westphalia and this federal state’s migration minister) is responsible for concluding these agreements.

Within the coalition, the SPD’s proposals have received support from the FDP. The Greens, meanwhile, are split over this issue. They are facing a dilemma because adopting a tougher stance – which is what both the majority of citizens and numerous local government officials representing the party are advocating – would lose them credibility in the eyes of their most fervent voters and trigger a conflict within the party. The importance of this dispute is evidenced by a joint letter written by the co-leader of the Greens, Ricarda Lang (who represents the left wing) and the minister-president of Baden-Württemberg, Winfried Kretschmann (who belongs to the more pragmatic group).[27] In this letter, they argued that not every immigrant who is currently residing in Germany is entitled to stay there permanently, and that the state has almost exhausted its potential to take in new asylum seekers. They also presented an alternative solution which involves curbing the inflow of asylum seekers, and argued that otherwise radical groups could gain ground and social divisions could be exacerbated.

Despite the party leaders’ work to reach a compromise regarding the migration policy, the Greens remain divided as they continue to hold on to one of their last remaining political principles. One manifestation of this was a dispute at a party convention in November 2023 during which, following a heated debate, most delegates supported the party leadership’s proposal to curb migration. At the same time, making changes in this area would require convincing the representatives of the Greens’ youth organisation and the party’s left wing. These groups have announced their intention to continue to advocate for the liberalisation of the present legislation. One form of pressure being put on the Greens involves Chancellor Scholz’s attempts to reach a consensus with opposition leader Merz regarding the proposal to curb the inflow of immigrants. Winning over the CDU/CSU would equate to securing the required parliamentary majority to amend the constitution. These amendments have been an increasingly popular discussion topic in Germany.

Proponents of radical reforms recall the beginning of the 1990s, when in response to a growing number of applications for protection and to attacks against immigrants carried out by far-right extremists, constitutional amendments were introduced to radically limit the number of instances in which foreigners were entitled to seek asylum in Germany. These modifications involved compiling lists of safe third countries and safe countries of origin to accelerate the processing of asylum applications. In addition, such a consensus with the Christian Democrats could enable the Bundesrat (in which the CDU has the votes to block some government initiatives) to approve the changes quickly. This could also help the state to maintain this policy in the coming years, and would be welcomed by German voters who appreciate cross-party cooperation on such important issues.

Despite the internal dispute over migration issues, which dates back to Chancellor Merkel’s decision not to shutter Germany’s borders in 2015, the CDU under Merz has attempted to unify the party’s stance. Meanwhile the Christian Democrats argue that the government’s proposals are far from sufficient. Therefore, one of this party’s main suggestions is to introduce an annual cap on the number of individuals Germany can admit (around 200,000). They have also demanded that border checks on Germany’s borders (including the one with Poland) should be maintained; deportation centres should be built in the vicinity of these borders for individuals whose asylum applications were rejected in an accelerated procedure; and that all voluntary programmes for admitting refugees (for example those from Afghanistan) should be cancelled. The CDU would also like to significantly reduce the number of instances in which immigrants who are already staying in Germany are entitled to bring in their families.

One important element of the party’s platform involves the proposal to identify Algeria, Morocco, Tunisia and India, in addition to Georgia and Moldova, as safe countries of origin. The Christian Democrats also propose to make radical cuts to social welfare benefits and to ban those individuals who are required to leave Germany (if, for example, their asylum applications have been rejected) from staying there. Moreover, the recent increase in anti-Semitic incidents in German towns and cities has consolidated the political demands put forward by the Christian Democrats, according to which immigrants would be required to declare their support for Israel’s right to exist as a state prior to being granted German citizenship. At the EU level, the CDU supports the proposals to strengthen Frontex and to boost the protection of the EU’s external borders. The latter proposal does not exclude the use of direct coercive measures. Other solutions endorsed by the CDU include the application of visa-related instruments as elements of pressure against those states which refuse to accept their own citizens back as deportees. The Christian Democrats would also like the asylum procedure to be carried out outside EU territory.[28]

VI. CONCLUSIONS: NO PROSPECTS FOR CHANGE

The migration crisis is so severe that the key dilemma the German political class is now facing is linked with a fundamental question regarding the state’s basic obligations. Do these obligations involve providing security to the state’s citizens in the first place, or to an abstract community of vulnerable individuals (while the list of threats they are exposed to is constantly increasing)? The lack of a clear answer and the government’s reluctance to use all the means legally available to it to protect the public are hindering the implementation of major changes in migration policy. However, Germany’s ongoing debate contains several proposals for actions which could result in a permanent reduction in the illegal inflow of immigrants. These include the following:

- A symbolic shift, such as Scholz annulling the declaration made by Merkel in 2015, which stated that Germany would not close its borders and was capable of admitting many more new immigrants. Proponents of making this symbolic shift refer to the attitude adopted by Germany’s neighbours, mainly Denmark and Austria. They argue that one element of such change should involve reducing the incentives which attract illegal migrants to Germany (see Appendix).

- Legal amendments. At present around 70% of individuals applying for protection in Germany are allowed to stay there, and without legal amendments this situation will not change significantly. It is necessary to both amend the legislation at the federal level (including the constitution, in a manner similar to the adoption of the 1993 amendment which limited the right to asylum) and to adjust EU legislation.

- Processing the asylum applications outside of the EU but in line with international law (for example, as part of the mission of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, as Germany is the second biggest contributor funding this body), and introducing a requirement for EU member states to take in contingents of individuals seeking protection. According to some politicians and experts, Germany is ready to take in around 200,000 such individuals annually. However, introducing such a mechanism would require a nationwide consensus in Germany, coordination of actions with other EU member states, and the identification of safe non-EU countries which would be willing to engage in such cooperation.

- Legal economic migration. Germany and the migrants’ countries of origin should establish partnerships a legal procedures for these countries’ citizens who are seeking employment in Germany, in exchange for their readiness to readmit those individuals whose asylum applications have been rejected (see Appendix).

These profound changes to the refugee and migration system would require the reaching of a consensus between the main political parties, as well as determination and consistency in seeking reforms which go beyond the practices applied thus far. Another important factor is the unique nature of the federation, which as regards the migration and refugee policy delegates comprehensive powers to the local administration structures. Realistically, a major decline in the number of asylum applications is unlikely in the foreseeable future. The solutions the government has proposed are merely half-measures which will not reduce the levels of illegal migration. To achieve this, coordinated action at the state, federal and EU levels is necessary.

Other obstacles to reducing the inflow of illegal immigrants include the German state’s excessive bureaucracy and the insufficient level of digitisation in its public administration. Disappointment at the lack of results of the political initiatives so far announced, combined with the state’s growing lack of agency, will raise the levels of support for radical anti-immigrant parties such as the AfD and the new project led by Sahra Wagenknecht, which will also be facilitated by the coming elections. The 2024 electoral timetable, which includes the elections to the European Parliament and three local elections in eastern federal states (Brandenburg, Thuringia and Saxony), will serve not only as the ultimate assessment of the SPD–Green–FDP coalition ahead of the federal elections, but also as a plebiscite on Berlin’s migration policy. A failure to modify the policy will affect the outcome of the elections to the Bundestag, which will be held in autumn 2025. If irregular migration continues to increase, this may spell the end of Germany as a welfare state in its present form, and aggravate the differences between the two communities living side by side, that is, the German community and the immigrant community.

APPENDIX

In its 2023 analysis, the Institute for Employment Research (IAB) indicated that 54% of those refugees who had arrived in Germany in 2015–16 had jobs, and most of them worked full time. Although a majority of these individuals (as much as 70%) were skilled workers, many worked in a job which was below their skill level. A mere 7% of the refugees found employment in the first year of their stay in Germany. This figure rose to 54% after six years and to 62% after seven years. A major divergence was recorded in these statistics for men and women: six years after their arrival in Germany 67% of men had a job, but only 23% of women (rising to 39% after eight years). There are no barriers to finding employment in Germany for immigrants with refugee status or those who have been granted asylum.

Asylum seekers are entitled to employment after three months in Germany. This also applies to individuals who are entitled to the so-called ‘tolerated stay’. Immigrants are not allowed to seek employment as long as they are staying in a refugee centre. The situation is different in the case of applicants hailing from a country listed as a safe country of origin; they are not allowed to work throughout the entire duration of their asylum procedure.

A study entitled ‘Ukrainian refugees in Germany. Part two’, published in August 2023, indicated that a mere 18% of Ukrainians of working age (18–64 years) have found employment, while in Poland the corresponding proportion is more than 80%. 39% of Germany’s working immigrants work full time, 37% part time, 18% have temporary jobs, and 5% are undergoing vocational training. As regards those immigrants of working age who are not employed, 93% of them have declared their willingness to take up a job, including 81% immediately or within a year, and 19% within two to five years. At present, a mere 3% of women with children aged 3 and younger find employment. This is linked to problems regarding excessive bureaucracy (for example the procedure for starting one’s own business activity), the complicated tax system and the system of recognition of school certificates and university diplomas, as well as Germany’s prioritising social adaptation over employment (emphasis is placed on participation in integration and language classes rather than on seeking employment).

However, Germany is expecting a rapid increase in the employment statistics for Ukrainian refugees. At present, around 70% of those immigrants who have no job are attending language and integration classes (62%) or vocational schools (8%). A relatively large proportion of Ukrainian women refugees used to work in academic, technical and medical jobs in those sectors of the economy in which Germany has recorded a major shortfall of workforce. At present, 49% of working Ukrainian immigrants have a job which is below their skill level (this mainly concerns women). This is mainly due to the lengthiness of the process for recognising their professional qualifications and their insufficient knowledge of the German language.

At present, Germany has around two million vacancies.[29] In addition, individuals born during the population boom of the 1960s are retiring, which means that the number of vacancies will rise by another 400,000 annually. According to IAB estimates, by 2035 the total shortfall of workforce on the German job market will be around 7 million individuals.[30] The problem is evident in all sectors of the economy and is not limited to highly skilled workers. The situation not only hampers the development of specific companies but also prevents the introduction of relevant changes in the education system, refugee integration and health care. Moreover, it is posing an existential threat to the German economy. Although the automation and digitisation of the job market could bring some improvement, thus far these factors have actually been the ‘Achilles’ heel’ of Germany’s economy and administration. As a consequence, the country now needs to hire foreign employees.

So far, Germany’s strategy has mainly involved attracting employees from other EU member states and liberalising its job market to make it more open to highly skilled workers from third countries (non-EU, the EEA and Switzerland). Although several legal amendments (such as the so-called migration package adopted in mid-2019)[31] became effective on 1 March 2020, their implementation was hampered to a great degree by the COVID-19 pandemic. Nor have they resulted in a major improvement on the German job market. Other liberalisation initiatives included the facilitations introduced before the Russian-Ukrainian war (which covered both Ukrainians and other nationals), and, most importantly, the SPD–Green–FDP coalition’s initiative to simplify the procedures for immigrants seeking employment. This involved facilitating the procedure applied to individuals who had resided in Germany on the basis of the so-called ‘tolerated stay’, and established a system of points modelled on the Canadian system. New legislation in this respect, especially the provisions intended to encourage foreigners to legally migrate to Germany to seek employment there, are expected to fill the gap on the job market and to help Berlin to regain control of the inflow of immigrants. However, so far, Germany’s relatively insignificant attractiveness as a destination for economic migrants from outside the EU has been a problem. This was due to the language barrier, the excessive bureaucracy, insufficient digitisation, the complicated procedure for recognising diplomas, Germany’s tax system, and other factors.

A regulation adopted in 2016 regarding the Western Balkans (the so-called Westbalkanregelung) has been the only mechanism to ensure an effective and legal process of hiring foreign employees on a large scale, in exchange for eliminating the illegal migration route leading to Germany. On the basis of this act, facilitated access to the German job market was offered to the citizens of Albania, Bosnia & Herzegovina, Kosovo, North Macedonia, Montenegro and Serbia (it should be noted that these countries have been put on the list of safe countries of origin, which de facto prevents their citizens from applying for asylum in Germany), although they are not allowed to take up temporary jobs. To find employment in Germany they are required to obtain a permit. Prior to issuing such a permit, the Federal Employment Agency checks whether any citizens of Germany and other EU member states have applied for the specific job, and whether the terms and conditions of employment are identical to those offered to the local workforce. Recently, the government decided to double the number of employment permits which can be issued to the citizens of the Western Balkan states. Starting from 2024, this will involve 50,000 permits annually.

The law enacted in July 2023 on the continued development of skilled immigration is expected to accelerate the inflow of a foreign workforce to Germany. It has eliminated numerous barriers to employing foreigners; for example, it has reduced the language-related requirements. For some jobs, especially those in which the shortfall of workforce is most prominent (such as nursing), the new legislation liberated the procedure of hiring individuals who have extensive practical job experience. In the facilitated procedure, individuals may simply be required to document the qualifications which they obtained by taking part in a training organised by a German chamber of commerce abroad. In addition, the immigrants are required to have at least two years of experience in a specific job.

Berlin continues to hope that the EU Blue Card will contribute to large numbers of well-educated workers arriving in Germany. According to the amended legislation, more individuals will be eligible for employment. These include foreign academics who obtained their university diploma within the last three years. They will receive the Blue Card provided that their German employer offers them a remuneration of at least €40,000 annually.

The so-called ‘opportunity card’ is expected to initiate a revolution in attracting foreign workers to the German job market. It will enable foreigners to take up a job and stay in Germany on the basis of the points allocated to these individuals, including for their education, foreign language skills (level A1 in German or B2 in English), professional experience and their links with Germany. To obtain this document an applicant needs to collect six points. Initially, the residence permit will be issued for one year (although this can be prolonged), provided that the applicant has funds to support themselves throughout that period. However, the card’s effectiveness will depend on the practical aspects of the permit issuance procedure, which in turn will depend on how well the administration is prepared to process the applications. This has been one of the major obstacles for economic migrants when choosing Germany as their destination.

Enabling individuals seeking protection in Germany to take up a job in a fast-track procedure will be another element in expanding the system for economic immigration. In line with the new legislation, asylum seekers will be allowed to find employment after six months of their stay in Germany, rather than nine. Another modification involves the rules of the so-called ‘tolerated stay’ of immigrants whose asylum applications have been rejected. They will be allowed to stay in Germany, provided that they have a job or take part in training. The so-called ‘tolerated stay’ is granted to individuals who are well integrated into society, able to support themselves and who pay the social insurance contributions required of employees. Moreover, on 1 January 2023 the Opportunity Residence Act came into effect. According to this law, individuals enjoying tolerated stay who have lived in Germany for five years or longer, as at 31 October 2022, will receive a residence permit alongside their family members for a ‘trial period’ of 18 months, during which they will need to find employment to support themselves and to learn German. In addition, their identity must have been definitively established. In the first half of 2023, 22,000 foreigners applied for a permanent residence permit in Germany as part of this procedure. The federal government estimates that more than 136,000 immigrants will use the procedure offered by the new regulation.

Furthermore, the ruling coalition is planning to accelerate the procedure for obtaining German citizenship. The waiting time is to be reduced from the present eight years to five, and in exceptional cases (for example involving individuals with special achievements for Germany) to three. At the same time, dual citizenship will be allowed. This is intended to encourage foreign workers to settle in Germany and, most importantly, to facilitate the integration of foreigners who have lived in Germany for some time. To be granted German citizenship, the immigrant will be required to speak German, and adult applicants will be expected to prove that they are able to support themselves. Individuals who have committed crimes motivated by anti-Semitism or racism will be banned from applying for naturalisation. In addition, all children born in Germany to parents who are not German citizens will automatically be granted German citizenship while being allowed to retain the citizenship of their father’s or mother’s country of origin. However, this will only be possible if one of the parents has been legally resident in Germany for more than five years and has been granted an unlimited residence permit. According to statistics compiled by the Federal Ministry of the Interior, around 14% of Germany’s residents, that is around 12 million individuals, do not hold German citizenship. Of this number around 5.3 million individuals have lived in Germany for at least ten years. According to the ministry, in 2023 168,000 individuals submitted their citizenship applications, and 3% of them had resided in Germany for at least a decade.

[1] ‘“We can do it” – the moral imperative and the needs of the labour market’ [in:] A. Kwiatkowska, ‘Cinderella became the Empress. How Merkel has changed Germany’, OSW, Warsaw 2021, osw.waw.pl.

[2] A. Ciechanowicz, ‘Niemcy: kolejne zaostrzenie regulacji azylowych’, OSW, 3 February 2016, osw.waw.pl.

[3] K. Frymark, ‘Porozumienie UE–Turcja: niemieckie reakcje’, OSW, 23 March 2016, osw.waw.pl.

[4] G. Erler, M. Gottstein, Lehren aus der Flüchtlingspolitik 2014 bis 2016: Überlegungen für die übergreifende Kommunikation, Koordination und Kooperation, Heinrich Böll Foundation, July 2017, heimatkunde.boell.de.

[5] K. Frymark, K. Kłysiński, ‘A surge in the number of illegal border crossings in Germany’, OSW, 29 June 2023, osw.waw.pl.

[6] See ‘Flüchtlinge aus der Ukraine’, Mediendienst Integration, mediendienst-integration.de.

[7] K. Frymark, ‘Ukrainians are slowly adapting to life in Germany’, OSW, 25 August 2023, osw.waw.pl.

[8] K. Woitsch, ‘Appell eines Grünen-Landrats zur Asyl-Politik: „So schaffen wir es nicht”’, Merkur.de, 27 April 2023, merkur.de.

[9] In November 2023, Germany made an attempt to modify the system and agreed on a “new” subsidy of €7500 per refugee. This was the result of negotiations launched six months earlier. See K. Frymark, ‘Dispute over funding refugees’ residence in Germany’, OSW, 11 May 2023, osw.waw.pl.

[10] ‘ARD-DeutschlandTREND’, Infratest dimap, October 2023, infratest-dimap.de.

[11] A. Kwiatkowska et al, Making up for lost time. Germany in the era of the Zeitenwende, OSW, Warsaw 2023, osw.waw.pl. See also K. Frymark, ‘The Wagenknecht party. Germany’s new protest party’, OSW, 24 October 2023, osw.waw.pl.

[12] See A. Kwiatkowska, Strangers like us. Germans in the search for a new identity, OSW, Warsaw 2019, osw.waw.pl.

[13] Ibidem.

[14] This concerns, among other things, schools placing emphasis on teaching the German language rather than other skills, and also avoiding the organisation of trips to locations such as museums linked with the history of the Jewish people.

[15] ‘Polizei meldet deutliche Zunahme der Angriffe auf Geflüchtete’, Spiegel, 14 November 2023, spiegel.de.

[16] K. Frymark, ‘The Turkish campaign in Germany. Rising tensions between Berlin and Ankara’, OSW Commentary, no. 234, 23 March 2017, osw.waw.pl.

[17] A. Kissler, ‘Deutschland unternimmt längst nicht genug gegen den muslimischen Antisemitismus’, NZZ, 17 October 2023, nzz.ch.

[18] See K. Frymark, ‘Germany: the consequences of the New Year’s Eve riots’, OSW, 10 January 2023, osw.waw.pl.

[19] M.F. Serrao, ‘Deutschland wird immer bunter und immer dümmer: warum die katastrophalen Pisa-Ergebnisse keine Überraschung sind’, NZZ, 5 December 2023, nzz.ch.

[20] Reply from the municipal authorities of Berlin to a parliamentary question asked by the AfD; see ‘Berliner Schüler mit Migrationshintergrund oft in der Überzahl’, BZ Berlin, 4 April 2018, bz-berlin.de.

[21] K. Frymark, ‘The shades of German anti-Semitism’, OSW Commentary, no. 301, 16 May 2019, osw.waw.pl.

[22] A. Jürgs, ‘Zerreißprobe im Klassenzimmer’, Frankfurter Allgemeine, 15 November 2023, faz.net.

[23] ‘Prorosyjskie demonstracje w Niemczech’, OSW podcast, 21 April 2022, youtube.com.

[24] ‘Anfeindungen und Angriffe im Zusammenhang mit dem Krieg’, Mediendienst Integration, February 2023, mediendienst-integration.de.

[25] K. Frymark, ‘Too green, too fast, too dear. The AfD is gaining popularity in Germany’, OSW Commentary, no. 518, 20 June 2023, osw.waw.pl.

[26] An interview with Chancellor Scholz by C. Hickmann and D. Kurbjuweit, ‘„Wir müssen endlich im großen Stil abschieben”’, Der Spiegel, 20 October 2023, spiegel.de.

[27] W. Kretschmann, R. Lang, ‘Nicht jeder kann bleiben: Fünf Vorschläge für mehr Ordnung in der Migrationspolitik’, Tagesspiegel, 1 November 2023, tagesspiegel.de.

[28] The stance of the CDU/CSU parliamentary group: ‘Deutschland-Pakt: Maßnahmen zur Begrenzung illegaler Migration’, cducsu.de.

[29] Federal Employment Agency, Arbeits- und Fachkräftemangel trotz Arbeitslosigkeit, Berichte: Arbeitsmarkt kompakt, August 2022, statistik.arbeitsagentur.de.

[30] ‘Deutscher Arbeitsmarkt verliert bis 2035 rund sieben Millionen Menschen’, Handelsblatt, 21 November 2022, handelsblatt.com.

[31] This comprised seven laws. The most important ones were the laws on the immigration of a skilled workforce (Fachkräfteinwanderungsgesetz, FEG), supporting the employment of foreigners (Ausländerbeschäftigungsgsfördergesetz) and on tolerated stay during vocational education and employment (Gesetz über Duldung bei Ausbildung und Beschäftigung).