Another extension of the trusteeship over Rosneft’s German assets

On 7 March, the Federal Ministry for Economic Affairs and Climate Action (BMWK) announced a third extension of the trusteeship over Rosneft Deutschland (RND) and RN Refining & Marketing (RNRM), this time until 10 September. The German government took control of the German assets of Russia’s Rosneft back in September 2022 (see ‘Germany: the state takes control of Rosneft’s assets’). According to the law, a trusteeship can be put in place for six months and then repeatedly extended for the same period if Germany’s energy security requires it. During this time, the company’s formal owner loses the right to manage their assets; these powers are transferred to a government-designated entity, in this case the Federal Network Agency (Bundesnetzagentur).

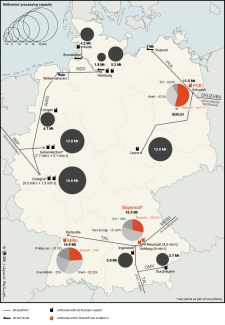

The government issued an explanatory note which stated that the extension of state control over RND and RNRM was necessary to guarantee the proper functioning of the refineries in which these companies hold stakes (see map). Business partners, financial institutions and insurers are expected to refuse all cooperation with companies managed by the Russian entities. Many of the contracts that were signed in recent months reportedly contain clauses that allow for such cooperation to be terminated should control over these companies revert to Rosneft. Severing cooperation, for example with regard to contracts for oil supplies, would paralyse the operations of plants that are crucial to Germany’s fuel security.

The document stated that the agreement which the German government had concluded with Rosneft on 28 February commits the Russian company to divest its German assets by the end of August. BMWK noted in its statement that the voluntary sale of shares by the owner is the “legally safest and fastest way” to guarantee that the refineries retain stability and receive investment. In early February, the ministry formally summoned the Russian owners for talks in a potential prelude to an expropriation procedure.

Commentary

- Since Rosneft’s assets were placed in the trusteeship, which is a temporary measure by its nature, Germany has been looking for a way to oust the Russians from the plants that form part of the country’s critical energy infrastructure. In April 2023, it passed legislation to allow for these assets to be expropriated, with compensation provided, if Germany’s energy security requires it. However, the initial steps it has taken in this direction in recent weeks have not only met with a harsh reaction from Russia, which has pledged to take retaliatory steps, but reportedly also encountered opposition from the Chancellery and the Ministry of Finance. The former is reported to be particularly concerned about the Kremlin’s possible retaliation against German assets in Russia while the latter is worried about a multi-billion-dollar compensation package (estimated at up to €7–8 billion, which would be equivalent to the value of these assets) it would have to pay from the state coffers during a period of budgetary austerity.

- It is also possible that the announcement of a potential expropriation was merely a way of forcing Rosneft to voluntarily divest its assets. The German government already held talks on this issue last year, but according to German negotiators, the Russian side was only playing for time by pretending that it was ready to sell. It took the threat of expropriation to create a new dynamic in this regard. According to the Handelsblatt daily, officials from the Chancellery and BMWK met with Rosneft’s CEO Igor Sechin in Istanbul last February to discuss allowing the Russian company to voluntarily divest its assets in return for payment and Germany’s withdrawal from its plans for nationalisation. Following these talks, the company declared that it was ready to sell and withdrew its complaint with Germany’s Federal Administrative Court against the previous extension of the trusteeship.

- From Germany’s perspective, allowing Rosneft to divest its assets in Germany has both positive and negative sides. On the one hand, it makes it possible to resolve the issue of Russian participation in Germany’s strategic energy infrastructure while avoiding additional strains in relations with Russia, difficult-to-assess legal risks and the federal budget being burdened with a multi-billion-dollar compensation package. On the other hand, it carries certain risks. Firstly, it is possible that Rosneft is still trying to play for time and merely pretending that it wants to sell its assets. At a later stage, this scenario would lead to political problems in Germany (particularly ahead of the September elections in Brandenburg, which is home to the PCK refinery in Schwedt, a key industrial site for the entire region) and would eventually force the government to resort to the expropriation option anyway. Secondly, Germany is ceding the initiative to the Russian side in selecting an investor or investors; a separate sale of individual shares to different parties appears possible and even likely given the scale of the expenditure and the diversity of the assets.

- At this stage, it is a completely open issue who Rosneft could sell its stakes to. When it chooses a buyer, it may be guided not only by financial-business considerations, but also by strategic-political calculation. From the Russian perspective, the Kazakh company KazMunayGas would be a convenient partner. It has signalled its interest in buying a stake and has already been selling oil to the PCK refinery in Schwedt using the Druzhba oil pipeline that runs through Russia, Belarus and Poland. The PCK’s works council would welcome this investor. If this partner is selected, Russia would retain both the transit revenue and the ability to block the route and use it to play political games. However, it is unclear whether the German government would accept the sale of shares to KazMunayGas and it has the legal possibility of blocking such deals if non-EU investors are involved. Meanwhile, as Russia has been given the initiative in selecting a buyer, any involvement of Polish companies, which has been the subject of speculation in recent months, appears unlikely. It also remains unclear whether it will be possible to transfer the funds from the new investor’s buyout of the assets directly to Russian accounts or whether they will remain frozen as long as the EU sanctions are in place.

Map. Oil transport infrastructure and refineries in Germany

Source: Association of the German Petroleum Industry (MWV, from 2021 – En2X).