Parliamentary elections in Croatia: the president challenges the Christian Democrats

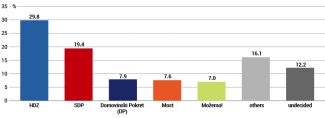

In the coming months, Croatia will face a series of elections that will determine the shape of its political scene for the years ahead. Elections for the single-chamber parliament, the 151-seat Sabor, will be held on 17 April; these will be followed by European Parliament elections in June, and then the presidential elections, most likely towards the end of the year. Two political parties have predominated in the country’s politics over the past two decades: the centre-right Croatian Democratic Union (HDZ) and the centre-left Social Democratic Party of Croatia (SDP). Since 2015, however, this duopoly has been challenged by anti-establishment parties which represent both the right and the left wing of the political spectrum.

The April elections will be a litmus test for the hegemony of the Christian Democrats (HDZ), who have ruled the country for a total of 26 years since 1991. Despite numerous corruption scandals the party, founded by Croatia’s first president Franjo Tuđman, can rely on the steady support of around 30% of Croatian citizens. Surprisingly, the incumbent prime minister and HDZ leader Andrej Plenković, who has been in power for eight years, will have to face a serious challenge from the controversial but popular President Zoran Milanović, who originates from the SDP. The president’s involvement in the campaign is unlikely to lead to victory for the left’s camp, but it could make it difficult for the HDZ to gain the majority necessary to form a stable government.

A recap of the HDZ’s rule

In 2020, Plenković formed a minority government in coalition with the Independent Democratic Serb Party. However, it was the support of other national-minority groups, small liberal parties and independent MPs that have enabled him to maintain a stable rule. The HDZ campaign is focused on the successes of their eight-year rule: entering the eurozone and the Schengen area (1 January 2023), opening the bridge on the Pelješac peninsula and the LNG terminal on the island of Krk, and carrying out tax reforms. The Christian Democrats, as part of their election campaign, are using the slogan that they respond to ‘all challenges’, and are reminding voters of their effective response to unprecedented crises in recent years (the COVID-19 pandemic, the Russian invasion of Ukraine, high inflation and the earthquakes in 2020).

Foreign policy is an important topic in the campaign. It has largely revolved around the EU mainstream, an approach which was expected to strengthen the country’s position in the region and within the EU – and thus cover up the government’s incompetence in addressing domestic issues and stagnation. In the HDZ’s vision, Croatia is a loyal partner of the EU and the US and a supporter of Kyiv (to which it has donated all its Mi-8 helicopters); but it also has some influence on European politics, especially concerning Bosnia and Herzegovina, which is a crucial issue for Croats (primarily improving the position of ethnic Croatians living there). Zagreb has joined initiatives supporting the enlargement process for the Western Balkans, for example, effectively lobbying for the accession negotiations with BiH to be opened (see ‘The EU is starting accession talks with Bosnia and Herzegovina’). The key symbols of the Prime Minister’s effectiveness on the EU arena are the adoption of the euro and joining the Schengen area, which have permanently anchored Croatia to the so-called ‘hard core’ of the EU.

However, the Plenković government has also been marked by numerous scandals and failures. These have led to as many as 30 ministerial dismissals (the ministers in charge of some departments have been replaced several times). The coalition’s incompetence was most evident when it was faced with challenges linked to rebuilding the areas affected by the earthquake. This showed that the HDZ was unable to govern the country effectively. Despite eight years in power, the Christian Democrats have failed to resolve many of the country’s most important problems, such as depopulation, uneven regional development, the economy’s dependence on tourism, excessive bureaucratisation and the declining quality of public services (see ‘The fading star pupil: ten years of Croatia’s membership in the European Union’). Frequent incidents of corruption, including government officials concealing assets, the embezzlement of national and EU funds, and preferential treatment for companies and enterprises linked to the HDZ, are a serious problem. Corruption and nepotism have become ingrained in this party’s governance model. According to the Eurobarometer, in 2023 as many as 96% of Croatians believed that corruption was a widespread phenomenon in their country. Regardless of this, the HDZ enjoys stable support from a 30% core of well-disciplined voters, partly due to its extensive network of political-business and clientelist connections.

The SDP’s reactivation: a one-man show

The centre-left SDP, with a post-Communist background, is the largest opposition party. However, since its defeat in the 2015 elections it has been grappling with numerous internal problems. These include interpersonal conflicts, a lack of strong leadership, and an ideological crisis stemming from the party’s departure from a left-wing agenda during the period when the incumbent president Milanović served as prime minister (2011–15). The SDP is also facing competition from new parties advocating left-wing, environmental or workers’ rights agendas. This has translated into a decline in support for the SDP; polls in early March indicated a support level of around 16%.

A bloc of ten left-liberal parties (excluding the Možemo! movement, which has been in power in Zagreb since 2021) planned to run together in the elections under the leadership of the SDP. However, when Milanović announced on 15 March that he would be the SDP’s candidate for prime minister, this coalition broke up, as some parties considered this move illegal. Although the Constitutional Court ruled that the president cannot run in elections or participate in campaigns without resigning from his office six months before the end of his term, Milanović is endorsing a coalition of five parties running under the Rivers of Justice (Rijeke pravde) slogan and promising to create a rainbow coalition that will remove the HDZ from power and form a ‘government of national salvation’.

Milanović’s actions are aimed at leveraging his approval ratings as Croatia’s most popular politician in recent years and bolstering the struggling SDP. The president’s controversial statements — such as his criticism of EU institutions and the West’s support for Ukraine, drawing upon nationalist slogans and overtly pro-Russian opinions — have earned him the sympathy of some right-wing voters. The president also seems to have ambitions to exert real influence on the country’s politics (constitutionally, his competencies are mainly limited to representative functions).

Searching for an alternative option

Since 2015 there has been a visible fatigue with the two-decade-long political duopoly, with the traditional parties appearing increasingly ideologically similar, and the sharp personal disputes between the prime minister and the president dominating the last term of the HDZ rule. The ideological proximity of the two largest parties is manifesting itself in a feeble and uninspiring campaign (the SDP is focused on attacking the government for corruption, while the government is showcasing its successes). Despite a strong economy (with a GDP growth of 2.8% in 2023 and inflation reduced to 4.1% by January of this year), pessimism prevails among the Croatian public. According to a Crobarometer poll in January this year, up to 70% of respondents believe that their country is heading in the wrong direction, and 65% do not support the government’s policies. The distrust in the traditional parties is causing voter demobilisation and falling turnout (which was only 47% in the parliamentary elections in 2020, the lowest in history) and relatively good results for populist candidates and anti-establishment & anti-system parties (especially those formed just ahead of the elections) on both sides of the political spectrum in subsequent elections.

Among the political forces competing for the votes of the right-wing electorate are the sovereigntist Homeland Movement (Domovinski Pokret) and the anti-establishment Most party (each with about 8–10% support); both of them are accusing the HDZ of betraying conservative values and pursuing a pro-European policy at the expense of the nation’s interests. Meanwhile, the Možemo! movement of urban activists is emerging as the leader of the left-wing, pro-ecological scene.

Prospects for the Croatian political scene

Prime Minister Plenković decided to call the election ahead of schedule (the parliamentary term ends in September this year) because, with the opposition demobilised and fragmented, he was confident of winning it. He is also aiming to strengthen his own position and that of his party ahead of the European Parliament elections (he has expressed his ambitions for a career in EU/international institutions). Milanović’s involvement has changed the dynamics of the campaign and introduced an element of uncertainty into the upcoming vote. The president has become an electoral driving force for the SDP, which had been mired in stagnation; this has now translated into a significant increase in support for the party (by up to 10 percentage points). It remains unclear whether this trend will continue and how it will affect the election outcome, as Milanović’s declaration has also mobilised the HDZ and its electorate. Moreover, the campaign itself has turned into a personal clash between the two key politicians.

Plenković and his coalition partners will benefit from the electoral system, which rewards both large, strongly consolidated parties and fragmented, regionally concentrated movements, as the 5% threshold applies in certain electoral districts (10), not nationwide. So far, the low turnout has played into the hands of the ruling Christian Democrats, as the HDZ has the most disciplined and best-organised grassroots structures. Furthermore, in 2023 it amended the regulations concerning the delineation of electoral districts, which the opposition parties claim are favourable to the HDZ (the aim was to adjust the number of seats to the number of voters). Recent polls indicate that the HDZ will win the most votes, but the elections‘ final outcome will largely depend on turnout. However it is not easy to predict how large that will be, as the president decided that the vote will take place on Wednesday (which will be a day off from work), rather than on Sunday as usual.

A better result for the SDP coalition may make it difficult for Plenković to form a stable government and will significantly prolong the process of its formation, especially considering the differences in the political agendas of the party’s potential allies and their reluctance to co-govern with minority groups, who are the HDZ’s usual coalition partners (they are guaranteed eight seats). Milanović himself may also attempt to form a very broad coalition united by the desire to remove the Christian Democrats from power. If he succeeds, it will then be necessary to hold a snap presidential election. The results of the parliamentary elections will influence the vote for the European Parliament and Croatia’s negotiating position during decisions on key appointments in EU institutions. This means that the coming months will have a decisive impact on the shape and stability of the national political scene in the years to come.

Chart. Support for political parties (March 2024)

Source: IPSOS poll of 25 March (1000 respondents), from Opinion polling for the 2024 Croatian parliamentary election, en.wikipedia.org.