Ukrainians’ EU migration prospects

The political crisis in Ukraine, particularly the bloodshed seen on 18-20 February and the subsequent Russian intervention in Crimea, has sparked fears of another possible wave of immigrants heading to the EU. However, the country was partially politically stabilised (at least in its central and western parts), and this has made the scenario of a mass migration of people from Ukraine rather unlikely. If there is no civil war in Ukraine, any further development of the political situation in Ukraine may have only an indirect impact on the actual migration. Should the political instability continue, the Ukrainian economy remain in recession while jobs are available for Ukrainian immigrants in the EU, then an increase in the migration of Ukrainian citizens to the EU, including Poland, would be possible. In the short term there may be two characteristic groups of immigrants: (1) young people who will attempt to leave Ukraine for good due to the lack of job opportunities; (2) circulating migrants, mainly from western Ukraine, who will be looking for temporary jobs. Only if the economic downturn trend and political turmoil in Ukraine continues for a longer time, will settlement migration increase.

The implications of the political situation

For over the 20 years that the Ukrainian state has existed, the tradition of political immigration has not developed, as opposed to the culture of labour migration . Ukrainian citizens are not included in the group of 30 nationalities which most frequently apply for refugee status in EU countries. In the “old” EU countries very few asylum applications by Ukrainian citizens have received media coverage, and in these cases the applications were due to discrimination on the grounds of sexual orientation or religious beliefs. However, in recent years unfair verdicts in trials and harassment on the part of the judicial system and the public order bodies have been mentioned as reasons for applying for refugee status. With regard to the November-February social protests in Ukraine, several hundred people decided to leave the country including those injured during the clashes in the Maidan who left to be treated abroad.

In the present situation, the goals of Kyiv Maidan protesters have been achieved and the provisional authorities are composed of supporters of the Ukrainian Maidan, and so there are no grounds to assume that political migration abroad on a national scale may increase . However, some intra-regional movements are possible. Ethnic Ukrainians from Crimea and Eastern Ukraine may decide to leave to other parts of Ukraine and to a lesser extend aboard. The same relates to Russian-speaking migrants who however will most probably choose Russia as their destination. It cannot be ruled out that certain people linked with the former Ukrainian leadership may request asylum in EU countries, fearing harassment from the new government.. Furthermore, a section of Ukrainian labour migrants who are currently residing in the EU may wish to extend their stay abroad due to the continuing political instability at home. Nevertheless, unless a civil war happens, these are not likely to be large-scale processes should not affect the proper functioning of the immigration systems of the EU countries.

At present there are visible signs of interregional tensions which could encourage the population from eastern or southern Ukraine to immigrate to the EU countries.. However the population in these regions is in general less inclined to consider immigration as an option. Secondly, inhabitants of Ukraine’s eastern and southern districts in the majority opt for Russia as the final destination of their emigration. Sailors are another important group of migrants from these regions of Ukraine are sailors and their employment depends above all on the job supply in particular destination countries, not on the situation in Ukraine. Some growth in the number of Ukrainians migrating to Russia after Russia’s military intervention in Crimea was observed. However, it is not possible to indicate the actual scale of this due to the high politicisation of that issue. In early March the Russian authorities stated that as many as 143,000 Ukrainians applied for asylum in Russia. This information was, though, later denied.

Another migration risk is linked with the direction of foreign policy that the new Ukrainian government will choose. If Russia toughens regulations regarding the right of Ukrainian workers to reside in its territory, for example following Ukraine signing the association agreement with the EU, Ukrainian workers may re-orientate their job search towards the EU markets.

In parallel, it is worth bearing in mind that the impact of protracted political crises on migration decisions is much more subtle and less researched than the influence of economic factors. Political factors may trigger mass immigration but this is above all the case when they substantially affect the quality of life of inhabitants in a given country, for example, the quality of public services, public security, the quality of education, the standard of health care, the general consensus in society and the level of tolerance for particular minority groups etc.

Labour migrants

In Ukraine's current post-revolution situation, the following factors will be crucial for further migration dynamics: the situation of Ukrainian migrants in EU countries and the country's further economic and social development.

Due to the intensive migration which has been ongoing since the beginning of the 1990s, Ukrainian citizens are becoming ever more firmly rooted in the EU countries[1]. Every year between half a million and a million Ukrainians are granted short-term visas to the Schengen countries; the number of long-term visas is also on the increase. A trend can be observed for Ukrainian immigrants to legalise their stay in the EU. In 2011 Ukrainian citizens received the most (204,000) residence permits (temporary or permanent) in the EU-28. The liberalisation of Poland's immigration policy played an important role in this process, including the introduction of the possibility to work temporarily without the obligation to receive a work permit. In 2012 Ukrainian citizens were granted over 223,000 permits of this kind and a further 137,000 in the first half of 2013[2].

Coupled with the trend to legalise the stay is a slow downward trend which may be seen with regard to the dynamics of Ukrainian emigration. Firstly, the deceleration of emigration may be attributed to Ukraine's demographic potential being exhausted, including above all the diminishing number of the population in general, which is linked to high migration rates, a low birth rate and a high mortality rate. Ukrainian society is still relatively young but within the next ten years the aging of the population will result in the number of people of working age diminishing[3] and it is this group who usually tend to migrate.. Secondly, fewer Ukrainians are deciding to leave the country due to limited job opportunities in a crisis-stricken EU.

The economic crisis in the EU hit in areas of employment such as construction and households (childcare and care, household chores) particularly hard and it is in these areas that Ukrainian migrant workers traditionally found jobs. Even though the significance of Russia as the final destination country for Ukrainian migrants is diminishing, it still has largest number of Ukrainian immigrants worldwide[4]. Some Ukrainian workers, formerly employed in the EU construction sector, moved to Russia to seek jobs as the economic situation there improved.

The current level of Ukrainian migrant stock [5] in the EU is estimated at approximately one million people. The most popular final destination countries are as follows: Poland, Italy, the Czech Republic, Spain and Germany. At present the number of Ukrainian labour migrants in Russia is at a similar level—estimated at 500,000 – one million people[6]. The circular migration, consisting of alternating periods of work abroad and in the country of origin, remains the most widespread type of migration for Ukrainians, although the significance of long-term emigration is also growing[7].

A possible forecast

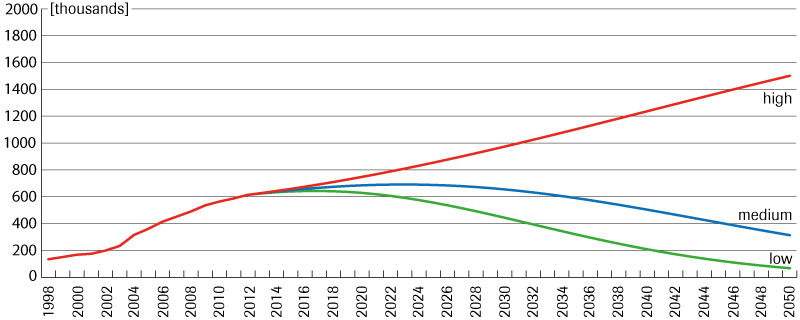

The initial findings of the report “Forecasting migration between the EU, V4 and Eastern Europe: the impact of visa abolition”[8] written by OSW and seven other research institutions from Central and Eastern Europe indicate that the most important factor encouraging Ukrainian migrants to go abroad are the high salaries they expect to earn in the countries of the EU and the jobs available there. The level of salaries and employment in Ukraine also has an impact, if slightly smaller, as well as favourable immigration policies of particular destination countries. Below are presented three forecast variants: the medium variant, high variant and the low variant. It must be borne in mind though that due to the imperfection of statistical data (many migrants still remain irregular, statistics poorly reflect circular migration, the statistical data provided reflect to a larger or smaller degree actual dynamics of migrations in particular EU countries) this forecast is more likely to point to tendencies rather than show actual figures. Furthermore, due to differentials in the methodology and the lack of long-term migration data, the initial model covers only 12 EU countries.

As is shown in the graphs included in the Appendix, the Ukrainian migrant stocks in EU countries may increase in the next few years (depending on economic parameters). This does not however necessarily mean that the migration dynamics will actually intensify; it is rather to a large extent dependent on the above mentioned tendency of migrants legalising their stay abroad. It can be clearly seen (except in the high variant ) that towards 2026 or 2028 the stock of Ukrainian citizens in the EU may start to diminish and this downward trend may persist in the long-term.

Circular migrants, young people and students

Should the economic situation in Ukraine deteriorate, the migration may intensify, particularly circular migration since this is the fastest method of responding to decreasing revenues of the population as it does notrequire wholesale life strategy changes but only a reorientation. . Furthermore, the sectors of EU labour markets in which Ukrainian migrants work are usually characterised by temporary, often seasonal work. Long-term migration requires greater preparation, including the alignment of professional qualifications, learning the language etc. However, in case of a prolonged crisis, the families of Ukrainian migrants residing in the EU may wish to join them.

Another group which may be more eager to leave Ukraine are people aged between 18 and 29, including students. As indicated in sociological studies people from this age category are more inclined to go abroad and care more about non-material assets such as education and professional development opportunities etc. Students who have the possibility to apply for different scholarships and exchange programmes constitute a special group. Nevertheless, there will not be a surge in the number of students leaving Ukraine, especially those who do not already have ties with the countries of the EU. Contrary to appearances, Ukrainian students are able to quite realistically assess the situation on the EU labour markets and while leaving Ukraine they take into account their linguistic competences, material resources etc. Poland may become an important destination country for Ukrainian students who already constitute the main group of foreigners studying at universities in Poland (9,747 students in the 2012/2013 academic year)[9].

Summary

The current development of the political situation in Ukraine does not indicate that the possibility of a substantial increase in the political emigration of Ukrainians exists, unless civil war breaks out. As for labour migration, should the socio-economic situation in Ukraine deteriorate, this may rise in the short term. Ukrainians will opt for those EU countries where there are the most job opportunities and the possibility of legal residence (due to the economic crisis of 2008-2012 a section of Ukrainian migrants have moved from southern European countries and the Czech Republic to Poland and, to a lesser extent, to Germany). Possible restrictions with regard to Ukrainian workers on the Russian labour market may cause part of this group to head for the EU. If the situation in the Ukrainian economy does not show signs of improvement, this may urge a greater number of Ukrainians to opt for circular migration. Permanentmigration may also increase, particularly among young people. However, in the long term substantial migration from Ukraine to the EU should not be expected.

Similarly, the possible lifting of the requirement for short-term Schengen visas for Ukrainians (entitling bearers to spend 90 days in every 180) should not cause a dramatic spike in the number of Ukrainians deciding to move to the EU. This stems above all from the liberal visa policy of the Schengen countries – Ukrainian migrants have a wide spectrum of legal possibilities to enter EU territory. Secondly, Ukrainian citizens will still not have the right to live and work in EU countries, which is the only measure that could significantly simplify their situation there and grant them conditions comparable to those which EU citizens enjoy. Were immigration levels to increase following a liberalisation of the visa regime, it will be rather short-term and will concern above all circular migrants. Those who often travel will find it easier to enter EU territory and then go back home. The lack of a visa requirement does not however solve the fundamental problem, viz. the availability of jobs for migrants.

If in the long term Ukraine chooses integration with the EU as its model of political and economic development, the importance of the EU as a final destination for migrants will be enhanced, at the expense of Russia. However, as with the issue of visa liberalisation, it is the working conditions that Ukrainian migrants are offered in the EU countries that will be of crucial importance.

Co-authors: Wadim Strielkowski and Tomas Duchac are on the academic staff the Charles University in Prague.

Appendix

Graph 1. Initial forecast of the number of Ukrainian citizens in 12 EU countries in 2013-2015: aggregated data (three variants)

Graph 2. Initial forecast of the number of Ukrainian citizens in 12 EU countries in 2013-2050 (medium variant)

This proprietary analysis is based on the econometric model examining interdependence between the Ukrainian migrant stocks in the EU and the level of GDP and the unemployment rate in destination countries and the sending country. It covers 12 countries (Austria, the Czech Republic, Denmark, Finland, Germany, Hungary, Italy, Latvia, the Netherlands, Slovenia, Spain and Sweden) and three scenarios of the development of the economic situation (intermediate – a 4% increase in GDP annually in Ukraine and 2% in the EU; low – a 6% increase in GDP in Ukraine and 2% in the EU; high – a 2% increase in GDP in Ukraine and 2% in the EU). Attention: this is a long-term model which was developed before Ukraine's economic results were published in 2013 (0% increase in GDP).

[1] Eurostat data; aggregated data for 2012 are not yet available.

[2] Data from the Ministry of Labour and Social Policy of the Republic of Poland.

[3] Forecast from the Institute for Demography and Social Studies at the National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine.

[4] International Labour Organization, Report on the Methodology, Organization and the Results of a Modular Sample Survey on Labour Migration in Ukraine, 2013.

[6] Ibid.

[7] International Labour Organization, op. cit. A. Pozniak, External labour migration of Ukraine as a factor of socio-demographic and economic development, CARIM East Research Reports 2012/04.

[8] The project is co-financed by the international Visegrad Fund; for more information on the project see: http://www.osw.waw.pl/pl/projekty/forecasting-migration-between-eu-v4-and-eastern-europe-impact-visa-abolition

[9] Data from the report “International students in Poland in 2013” prepared by the Conference of Chancellors of Higher Education Schools in Poland and the Perspektywy Education Foundation.