End of the grand coalitions

Both German politicians and commentators have been talking about the extraordinary importance of the forthcoming European Parliament elections for the future of the EU. The expected decline in support for the Christian Democrats and Social Democrats, combined with the gains expected for parties opposed to European integration, will lead to major changes in the way the parliament functions, and of the EU as a whole. The two largest European parties will probably not be capable of forming a stable coalition, and this in turn could affect who takes up the chief posts in the EU.

The results of the European elections could have repercussions for the ability of the grand coalition in Berlin to survive, and decisions regarding individuals in the CDU and SPD. For the German parties, this election is also the most important test before the autumn elections in three eastern federal Länder – in Brandenburg, Saxony and Thüringen. In addition, on 26 May, at the same time as the European elections, elections will be held for seats in the regional parliament in Bremen. For the SPD, loss of power in this federal state would present a major challenge, because the Social Democrats have been in power there for 74 years. More severe conflict and debate can be expected as to whether the CDU/CSU and SPD are to continue ruling collectively. If a minister of justice from the SPD wins a seat in the EP, this could lead to changes in Chancellor Angela Merkel’s government. It is possible that a reshuffle of Angela Merkel’s cabinet would involve appointment of CDU leader Annegret Kramp-Karrenbauer.

The election campaign in Germany

In Germany, the European elections will be linked to the elections to the Bremen regional parliament and a number of local councils. This will probably lead to a greater turnout (in 2014 turnout was 48%, while the average turnout in the EU was 43%), but also means that local and regional issues will be part of the campaign. The main campaign issues are climate protection, the environment, and providing funding for RES. Some proposals being made relate directly to German politics, and not the system in the EU. This is true of the proposal to introduce a CO2 tax, which would be levied for instance on fuel. The revenue generated by this tax would speed up transformation of Germany’s energy sector. Other issues of interest to voters are migration, security, the national debt, and stability of the euro[1].

Unlike the Bundestag and regional parliament elections, no minimum threshold applies in the EP elections. For German MEPs, apart from representatives of parties that hold seats in the Bundestag, this means that politicians in the National Democratic Party of Germany (NPD), for which the EP is the most important forum for political activity (the party is not represented in the Bundestag or the regional parliaments), will also take up seats, as will politicians in largely unknown groupings, such as the Party for Labour, Rule of Law, Animal Protection, Promotion of Elites and Grassroots Democratic Initiative, or the Ecological Democratic Party. The fact that there is no threshold encourages the smaller groupings and initiatives to run, and this is why 41 parties and associations are registered for the elections (25 in 2014).

The fact that there is no election threshold encourages smaller groupings to run for seats. More than 40 parties and associations have registered electoral lists.

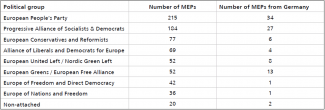

In Germany, there are 64.8 m registered voters (the largest number in the EU). This means that the result of the elections in Germany will have a major impact on the distribution of power in the EP. Voters in Germany determine the allocation of 96 out of 751 seats (if Brexit should come to pass – 705). During the last parliamentary term, German MEPs were represented in all of the political groups in the EP (see annex). Some of the long-serving and influential MEPs are not seeking re-election (for instance CDU member Elmar Brok, who has held a seat since 1980, and former Greens leader Rebecca Harms). This will result in a younger generation of German members, but also affect the way the EP functions, where effectiveness largely depends on the length of service of MEPs, and the posts they hold.

Test of the CDU leadership

For the Christian Democrats, the European elections will be the first leadership test since Annegret Kramp-Karrenbauer took over leadership of the CDU, and Markus Söder took over leadership of the CSU. The changes in these two parties have led to suppression of conflicts over personnel-related and manifesto policy between Angela Merkel and Horst Seehofer, and enabled a joint manifesto to be presented before EP elections for the first time in history. To date, joint manifestos were an issue reserved for domestic elections, while the CSU stressed a more conservative and Eurosceptic profile in a separate European manifesto[2]. The CDU’s healthy result (approximately 30% in the polls) will strengthen the new leader within the party and improve the Christian Democrats’ chances in the autumn regional parliament elections in the eastern part of Germany. In turn, if seats were to be lost in the EP and results were worse in Brandenburg, Saxony, and Thüringen, this would intensify the discussion within the party about Kramp-Karrenbauer’s leadership and strengthen her rivals (above all Friedrich Merz, who lost to Kramp-Karrenbauer in December 2018, and Armin Laschet, the prime minister of Nordrhein Westfalen). The elections will also be a test of the leadership for the CSU, and a test ahead of the local government elections in March 2020. The outcome will reveal whether stressing pro-European elements of the manifesto is an effective means for the CSU in the standoff with the AfD.

Unlike in 2014, the Christian Democrats will not be pinning their hopes on Chancellor Merkel. Merkel is not featured on campaign posters and has not been attending election rallies. This could prove to be a misguided strategy. Merkel continues to be the most popular German politician, and 68% of Germans want her to stay in power until the end of the current Bundestag term, which ends in 2021[3].

A successful result for the German Christian Democrats will enable them to fight for key posts in the EU. Manfred Weber, a member of the liberal wing of the CSU, is the candidate for the CSU, CDU, and the entire European People’s Party for EC president. His chances are undermined however by the sceptical approach of many European leaders to the idea of Spitzenkandidaten (leaders of the election campaigns of the European political parties tipped as candidates for the post of EC president). The President of France, Emmanuel Macron, objects to this procedure the most. Another area in which Weber is weak is lack of experience in government; he is the deputy leader of the CSU and leader of the EPP fraction in the EP.

The fall in support for the Christian Democrats and Social Democrats, and strengthened position of parties opposed to European integration, will radically change the way the EP functions.

Becoming EC President will depend on a range of factors, such as Weber’s and the EPP’s ability to form a broad coalition in the EP and alleviate the resistance in the European Council. Weber’s appointment might also be affected by the conflict over Fidesz’s membership of the EPP. Fidesz has already proven to be a major disruption for the Christian Democrats in the campaign before the European elections, primarily for the Bavarian CSU, which collaborates with the Hungarians[4]. It is also possible that one of the posts will go to a different representative of Germany, for example Jens Weidmann, head of the Bundesbank, who is named as a candidate for head of the European Central Bank. There is also continuing speculation that Angela Merkel might take over the role of head of the European Council, although Merkel denies this.

For the German Christian Democrats, one of the main tasks will be to maintain a strong position in the EPP, thereby retaining as much influence over the work of the EP as possible, for instance by gaining important posts (in EP committees, especially the EP Committee on Foreign Affairs, for example, which has been in the hands of the CDU since 1999, except for a break of five years, and posts in the EPP itself).

The Christian Democrats’ model for European integration, much publicised during the election campaign, is based on the principle of subsidiarity, which is to be controlled more efficiently. Manifesto speeches made have been critical of the excessive centralism and bureaucracy, and the vision of a European superstate has met with scepticism as well[5]. The head of the German Christian Democrats is in favour of the role of national states as a source of identification and democratic legitimisation, as well as the intergovernmental method, which she described as being an equally valid pillar in the decision-making process to the community method[6]. With regard to a common foreign and security policy, Kramp-Karrenbauer said, a joint seat held by the EU on the UN Security Council would ensure operational capacity in the future. At the same time, she would like to see a European Security Council formed, involving the United Kingdom, and in addition the CDU and CSU want to broaden the scope of issues for which a qualified majority vote is required. The Christian Democrats emphasise their opposition to creating the post of minister of finance for the eurozone, and rule out the possibility of Germany being part of a transfer union. According to the Christian Democrats, confirmation of the current rules on fair competition in the EU should be accompanied by an assurance that European businesses will continue to be competitive in relation to outside monopolistic entities that benefit from protectionism on the part of the country of origin. The Christian Democrats have said that they are in favour of keeping the current budget for the common agricultural policy and keeping in place the main principles of distribution of funds on the basis of direct subsidies.

SPD – social reform programme

Unlike since 2014, and unlike the Christian Democrats, the German Social Democrats cannot support their campaign using their own, main European Socialist Party candidate. This role has fallen to the Vice-President of the EC, Frans Timmermans, who is from the Netherlands. This time, the SPD campaign is headed by the incumbent minister for justice, Katarina Barley, who only has experience in domestic politics. On the other hand, the other main SPD candidate, Udo Bullman, does have the profile of a European politician. He is currently head of the Progressive Alliance of Socialists and Democrats in the EP.

For the Christian Democrats, the EP elections will be the first test of the new leadership – Annegret Kramp-Karrenbauer in the CDU and Markus Söder in the CSU.

The forecasts for the SPD are not good. The result is expected to be considerably less than the 27% gained in the 2014 EP elections, and even lower than the historical failure in the Bundestag elections in 2017 (20.5%). The SPD will therefore be weakened twofold in the coming parliamentary term – due to both a poorer general result of the European social democrats, and due to Germany having less representation in that political group. The party is still paying the political cost of a dispute over the co-creation of another grand coalition with the Christian Democrats following the 2017 Bundestag elections.

The attempt to curb the decline in popularity was based, at the beginning of 2019, on social welfare initiatives, and this was also included as an element of the manifesto for the EP elections[7]. The SPD is in favour of a social Europe as a counter-vision to neo-liberal ideas. The SPD’s most important policies include introducing a minimum wage in all member states, measures to converge pay and social security systems, and improving employment conditions and labour law standards. The Social Democrats are proposing creating a European reinsurance fund as a contingency measure in the event a crisis leads to a deterioration of conditions on the labour market in member states. They seek a larger role for the EU in tax policy, in particular abolishing member states’ veto and fundamentally expanding the scope of issues for which a qualified majority vote is required.

The SPD wants to see further integration, above all in the eurozone. In its manifesto, it recommends making use of options provided for in treaties for a narrower group of member states to work together more closely. The eurozone budget, pushed through by France, has the SPD’s support. This budget was intended to be used for investment and stabilisation. The SPD is also promoting the idea of appointing an economic government and minister of finance for the eurozone in the future. The European Stability Mechanism (ESM) would be transformed into the European Currency Fund. One noteworthy element is a declaration of readiness to increase Germany’s financial contribution to the EU budget, which would also be funded by a financial transaction tax. At the same time, access to EU funds is to be linked to observance of the principle of the rule of law, and a further long-term financial framework would be used to a greater extent for social policy goals. As part of the reform of the common agricultural policy, a proposal has been put forward to make payments conditional upon meeting social, environmental, and labour law standards. Regions and municipalities that agree to take in refugees are to have access to a special fund to support integration and communal development.

The expected poorer overall result of the European Social Democrats and the reduced number of seats held by Germans in this political group will weaken the SPD twofold.

The German Social Democrats took the term “European sovereignty” over from Emmanuel Macron, and are suggesting that it be achieved by reinforcing common foreign policy, putting an end to the unanimity requirement, strengthening the position of the High Representative of the Union for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy, and obtaining a seat for the EU on the UN Security Council in the future. The SPD has also taken advantage of the EP elections to renew its proposals for arms control. It has said that it supports the vision of a common European army, under parliamentary control – and this would also be a solution to a “resurgence of nationalism”. The SPD is proposing changes to the EP: giving it a right of legislative initiative, creating a new defence committee, allowing it full involvement in adoption of EU legislation on taxation, and expanding its monitoring and investigative powers. The SPD supports developing the principle of Spitzenkandidaten who are on transnational electoral lists. The EP would also have the option of asking for a vote of no confidence in individual EC members, and not just with respect to a whole college.

Upward trend for the Greens

The Greens have the greatest support among of all the political parties (up 10 p.p. compared to the EP elections in 2014). Having achieved an average result of 19% in the polls, the Greens are now potentially the second most powerful political group in Germany. The EP elections will be a means of verifying the increase in their political standing. To date, their support came primarily from a change of leadership and suppression of infighting, the continuing crisis in the SPD, tension in the grand coalition, and lack of involvement in the federal government, which has weakened the Social Democrats, for example. The main topic of the election campaign, environmental and climate protection, which Germans consider the most important task faced by the EU, will help improve the Greens’ result. Maintaining a high level of support both in the EP elections and the elections to the regional parliament in Bremen, where the Greens would like to remain in a coalition with the SPD, will help strengthen the party in the regional parliament elections in the eastern regions of Germany. In Brandenburg, Saxony, and Thüringen, where to date they have not been very well established, the Greens can expect support of between 7 and 12%, according to opinion polls.

The higher number of seats than that gained in 2014 in the EP will strengthen the German Greens within their own political group. This could also lead to greater influence in the new structure of the coalition, although lack of a representative in the European Council continues to be a fundamental weakness. Greater representation of the Greens in the EP could enable them to exert a greater influence on the subjects discussed and the conclusions reached. This is true not only of environmental issues, but also for example policy on Russia. The Greens have been critical of the policies of the Russian authorities, support keeping in place EU sanctions imposed following the annexation of the Crimea and aggression in Ukraine, and are opposed to Nord Stream 2.

The increase in the number of seats attained in the EP will make the German Greens stronger in their political group. Not having a representative in the European Council will remain however a fundamental weakness of the European Greens.

In the election manifesto adopted in November 2018, and during the campaign, the Greens stated that they supported making EU decision-making more efficient[8]. One of the ways in which the EU would become more efficient would be expanding the scope of issues for which a qualified majority vote is required in the European Council to include foreign, security, climate, and fiscal policy. The party would like to see the EP given greater powers in the form of legislative initiative, retaining the Spitzenkandidaten procedure, and powers in the appointment of directors of the European Monetary Fund, should this fund be set up in the future. In the Greens’ view, the EC should incorporate a parity system for women into commissioner appointments. The Greens agree that EU treaties could be amended if the amendments were drawn up by a convention created for this purpose and approved in a Europe-wide referendum. The party is in favour of an integration model that promotes more intense cooperation between selected countries (above all Germany and France), but which would essentially be inclusive. This applies for instance to the eurozone budget, which would potentially be open to all EU member states.

In their manifesto, the Greens emphasise allocation of EU funds for climate protection, renewable energy, funding for more impoverished regions and ecological agriculture, and new areas of social expenditure, for example to make young unemployed people occupationally active. Financing the common agricultural policy would do more to bring about a change in the agricultural model from large-scale industry to smaller, more environmentally-friendly crops and livestock. The Greens would also like to see a fund created (as part of agricultural policy) for environmental protection in agriculture of €15 billion per year. This new area of spending would be financed by increasing the contribution from the current level of 1% of member states’ GDP to 1.2% of GDP, and increasing EU revenue in the form of new taxes (digital, on CO2 emissions, and on the largest corporations). If Brexit takes place, the Greens will demand that the budget is replenished by increasing contributions.

AfD – repeat debut

Support for the AfD in the opinion polls remains at a level similar to that of the 2017 Bundestag elections, of 12.6%. The party can thus be expected to gain a result in double figures, considerably higher than 7.1%, which in 2014 gave the party, existing for a mere year at that time, seven seats. By the end of the term, the AfD only had one of those seats left, due to infighting, division, and secession. Five former MEPs in the AfD – including the founder, Bernd Lucke – departed in 2015. In 2017, following the former co-leader of the party, Frauke Petry, Marcus Pretzell left the party. Presently, from the AfD, a seat is held in the EP by co-leader Jörg Meuthen, who is in charge of running the election campaign. He has relatively little experience in Brussels and Strasbourg, however, because he did not replace Beatrix von Storch, who was elected to the Bundestag, until the beginning of 2018. The AfD is therefore starting in the EP as a novice.

Although in comparison to the ratings of Eurosceptic parties in other EU countries the AfD does not have a lot of support, it could play an important role in a potential parliamentary alliance between them. In the EP, the AfD initially collaborated with the Tories and was a member of the European Conservatives and Reformists, but towards the end of the term it only had one MEP, belonging to Europe of Freedom and Direct Democracy. This will probably not be established again in the new term. In April 2019, the AfD announced it was joining Italian Deputy Prime Minister Matteo Salvini’s initiative, and, as part of the European Alliance of Peoples and Nations, is to continue collaborating among others with Austria’s Freedom Party. At the same time, close links with the Austrians could discourage AfD voters due to release of controversial recordings of FPÖ politicians.

The most radical proposals are those of the AfD concerning abolishing the European Parliament and leaving the eurozone. They also want major European issues to be decided by way of a referendum.

In its manifesto, the AfD uses the slogan “Europe of Nations” to demand fundamental reform of the EU and a departure from the concept of federation[9]. The AfD’s most radical proposals are those concerning abolition of the EP as an undemocratic institution, leaving the eurozone, and even Germany leaving the EU if far-reaching reform of the EU proves impossible. It is indicative that members of the AfD themselves modify this proposal due to the overriding support for EU membership in Germany. According to opinion polls, 80% of Germans would vote to stay in the event of a hypothetical Dexit referendum. Opinion polls say that supporters of the AfD are divided over this issue – half are in favour of Dexit[10].

The party is opposed to further integration within the economic and monetary union, to strengthening the ESM, and expanding the banking union. It has rejected the idea of appointing a European finance minister, taxes set at European level, and coordination and harmonisation of social policy. According to the AfD, the EU budget should be reduced, and this includes by limiting spending on cohesion policy. The multiannual financial framework is to be agreed upon not for a period of seven years, but to correlate with the five-year EP term. With respect to the methods of settling the major European issues, the AfD is demanding that referenda be held.

Asylum and migration policy, including returning these powers to the states and abolishing the Schengen area, is a major element of the party’s manifesto. A position clearly at variance with the other political forces with respect to migration firstly assured the AfD revival following the split in 2015, followed by success in the regional parliamentary elections and Bundestag elections. In the current EP election campaign, the migration issue was however overshadowed by debates over climate policy, and eurozone issues were also pushed further down the agenda. The AfD’s denial of human impact on the climate is at odds with the public mood in Germany, where 34% of respondents say that climate protection is the greatest challenge the EU will face in the future, while the second greatest challenge is migration (32%)[11].

FDP back in the game

German liberals did not fully exploit their successful return to the Bundestag in 2017 (10.7%). The breaking off of talks with the Christian Democrats and the Greens cost them support. The EP elections are an opportunity for the FDP in two ways: the party will probably improve on its 2014 result (3.4%), and by the same token will gain more seats in the EP. In addition,

Most of German society is in favour of the EU, Germany’s membership of the EU, and a single currency. EU institutions also enjoy a level of trust among German respondents that is higher than the European average.

the FDP now has new political capabilities due to the alliance of the European liberals in ALDE with President Macron. The party is one of eight formations that began working together more closely on 11 May in Strasbourg. These include the French “La Renaissance“ (from La République en Marche – LREM) and the Spanish Ciudadanos, the Dutch D66, the Hungarian Momentum, Belgian MR, Austrian Neos, and Dutch VVD. These have the common objective of forming a political group in the EP, which, forecasts say, would have approximately 100 seats and could be strengthened by other groupings or individual MEPs. Secretary General Nicola Beer, one of seven leaders of the European liberals’ campaign, (together with Danish Competition Commissioner Margrethe Vestager) became the face of the FDP campaign.

The manifesto of the German liberals states that they are in favour of a federal vision of the EU[12]. They support creating a European convention to devise a new European constitution. They have proposed a review of powers in line with the principle of subsidiarity, and strengthening oversight of compliance with this principle. Their policies also include legislative initiative for the EP, a Europe-wide list of EP candidates, greater transparency in the decision-making process in the Council, reducing the EC, and prevalence of legislation in the form of directives over regulations.

With regard to economic policy, the FDP supports further expansion of the internal market. It is proposing a new stability pact for the eurozone, transformation of the ESM into a European Monetary Fund, and greater integration of capital markets. It has rejected the idea of a transfer union, and is proposing that deposits in the banking union be secured by way of a national mechanism. It is demanding reform of the EU budget to make it more efficient, without a change in quantity. The structure of the budget is to be reorganised through integration of instruments that have been separate to date, and abolition of discounts. Research, innovation, and digitalisation will take priority in the allocation of spending. With regard to foreign policy, on which liberals focus in particular, there is support for an EU foreign minister and applicability of a qualified majority in decision-making. They are in favour of a European army, adopt a pro-integration line with regard to migration and asylum policy, and seek strengthening of Frontex.

Divided left

For the Left, the EP elections will mainly mobilise the party’s voters ahead of the autumn regional parliament elections, which are much more important for this grouping. The support given in the polls in the region of 6 or 7% is below the party’s expectations (in the 2014 elections the Left gained 7.4%). This fall in the party’s ratings is due primarily to a negative election campaign pointing out the weakness of the EU, and internal divisions in the grouping (with regard to manifesto and individuals, including the decision of Sahra Wagenknecht, one of the most recognisable Left activists, not to run again for the leadership of the fraction in the Bundestag). The Left has chosen the younger generation of politicians (Özlem Demirel and Martin Schirdewan) to head the campaign, but this has not made the party more recognisable or led to an increase in support.

In its manifesto, the Left proposes increasing the EP’s powers for instance in the form of unlimited right of legislative initiative and broader control of the EP over the ECB[13]. In addition, it seeks a European referendum (but does not state the formal requirements). The Left considers subsidiarity and strengthening of regions (among other things in the form of funding for local authorities that take in refugees) as an overriding EU principle. The grouping would like to see the EU budget allocated in a way that focusses on fighting unemployment among young people, security for unemployment, and increased welfare spending. The Left is in favour of increasing spending on renewable energy sources and transportation infrastructure, and universal involvement of EU citizens in digitisation.

Stability in European politics, unknown factors in domestic politics

The broad pro-integration consensus of the German political parties corresponds to the positive view taken by most of German society towards the EU, Germany’s EU membership, and a single currency. EU institutions also enjoy a higher level of trust on the part of German respondents than the European average. At the same time, there is greater support for European integration than five years ago[14]. Also, opinion polls reveal that in recent years the number of people in favour of maintaining the status quo has risen to 33% (25% in 2012), while support for further integration and transfer of powers at European level remains at 17% (20% in 2012)[15]. The favourable view of the EU on the part of Germans is also reflected by a higher turnout for EP elections than the EU average. It remains to be seen whether discussions on the fateful nature of this year’s elections will mean greater voter mobilisation. 61% of respondents consider the forthcoming elections to be important, while among supporters of the Greens this number is 83%, PD – 78%, and the CDU – 76%[16]. For the German parties, it is important to win over voters in the Bremen elections, to be held on the same day, and in numerous municipal elections. At the same time, groupings that support European integration are trying to prevent the AfD becoming stronger, using to this end in particular the recordings that were compromising for the FPÖ, released one week before the elections, and the fiasco in the ruling coalition in Austria, of which it is part.

For all of the groupings, the EP elections are a general test prior to the autumn elections in three länder in the east. The outcome of the EP elections will be a method of gauging support, which can be used to examine the leadership capabilities of the ruling parties and an argument in the discussion about the future of the grand coalition. The pressure on the SPD authorities to leave the coalition with the CDU will grow along with the expected poor results in the next elections to be held this year. Review of the coalition agreement, scheduled for the end of the year, and the SPD conference scheduled for December, will be a pretext for leaving the government. In such a situation it is possible that Kramp-Karrenbauer will be given the task of forming a government within the new coalition. The coalition would probably be joined by the Greens and the FDP. Elections might also be held early, especially if coalition talks with new partners fail, and this would benefit the Greens, who have had a record increase in support in the polls, and currently have the smallest fraction in the Bundestag.

Annex

German MEPs in political groups in the eighth European Parliament (2014-2019)

Source: own list formulated on the basis of data published by the EP, valid as at 21.05.2019, http://www.europarl.europa.eu/meps/

[1] Europas Bürger glauben trotz Krisen an die EU, „Die Welt“, YouGov poll in eight EU member states, https://www.welt.de/politik/ausland/article193371401/WELT-Umfrage-Deutsche-halten-Umweltschutz-fuer-groesste-Herausforderung-der-EU.html

[2] See K. Frymark, Wolny Kraj Bawaria, „Prace OSW”, 15.04.2019, https://www.osw.waw.pl/pl/publikacje/prace-osw/2019-04-15/wolny-kraj-bawaria

[3] According to Politbarometer for ZDF of 10 May 2019.

[4] Ł. Frynia, R. Formuszewicz, The game to exclude Fidesz from the European People’s Party, „OSW Analyses”, 13.03.2019, https://www.osw.waw.pl/en/publikacje/analyses/2019-03-13/game-to-exclude-fidesz-european-peoples-party

[5] Presented in the CDU election manifesto: Unser Europa macht stark. Für Sicherheit, Frieden und Wohlstand, https://www.cdu.de/europaprogramm and in an article by Annegret Kramp-Karrenbauer entitled Europa jetzt richtig machen, „Die Welt am Sonntag", 10.03.2019, https://www.welt.de/politik/deutschland/article190037115/AKK-antwortet-Macron-Europa-richtig-machen.html

[6] R. Formuszewicz, Germany: Christian Democrats’ response to Macron’s appeal to the citizens of Europe, „Analizy OSW”, 12.03.2019, https://www.osw.waw.pl/en/publikacje/analyses/2019-03-12/germany-christian-democrats-response-to-macrons-appeal-to-citizens

[7] SPD election manifesto: Kommt zusammen und macht Europa stark!, Wahlprogramm SPD, https://www.spd.de/fileadmin/Dokumente/Europa_ist_die_Antwort/SPD_Europaprogramm_2019.pdf

[8] The Greens‘ election manifesto: Europas Versprechen erneuern, Wahlprogramm Bündnis 90/Die Grünen, https://cms.gruene.de/uploads/documents/2019_Europawahl-Programm.pdf

[9] AfD election manifesto: Programm der Alternative für Deutschland für die Wahl zum 9. Europäischen Parlament 2019, https://www.afd.de/wp-content/uploads/sites/111/2019/03/AfD_Europawahlprogramm_A5-hoch_web_150319.pdf

[10] Markus Wehner, Nachlassende Wirkung, „FAZ“, 15.05.2019.

[11] YouGov poll - see footnote 2.

[12] FDP election manifesto: Europas Chancen Nutzen. Wahlprogramm FDP, https://www.fdp.de/sites/default/files/uploads/2019/04/30/fdp-europa-wahlprogramm-a5.pdf

[13] Left election manifesto: Für ein solidarisches Europa der Millionen, gegen eine Europäische Union der Millionäre, Wahlprogramm DIE LINKE, https://www.die-linke.de/fileadmin/download/wahlen2019/wahlprogramm_pdf/Europawahlprogramm_2019_-_Partei_DIE_LINKE.pdf

[14] F. Mayer, Die neue Europafreundlichkeit, Politik & Kommunikation, 10.05.2019, https://www.politik-kommunikation.de/ressorts/artikel/die-neue-europafreundlichkeit-169978647

[15] IP-Forsa-Frage, 03/2019, https://zeitschrift-ip.dgap.org/de/ip-die-zeitschrift/archiv/jahrgang-2019/mai-juni-2019/ip-forsa-frage-032019

[16] Die Mehrheit der Deutschen findet die Europawahl wichtig für Deutschland, 16.05.2019, https://yougov.de/news/2019/05/16/die-mehrheit-der-deutschen-findet-die-europawahl-w/