The Caucasus deregulated. The region on the anniversary of the end of the second Karabakh war

A year after the end of the second Karabakh war, the situation in the South Caucasus evades simple definition. On the one hand, it seems relatively stable: most of the provisions of the tripartite Statement[1] that gave rise to the end of the fighting are being implemented. Moreover, apart from a defeated and weakened Armenia, all the actors involved in the war have reasons to be satisfied: Azerbaijan has regained control of most of the disputed territories and has proved its strength; Turkey, which supported Baku, has reaffirmed and expanded its influence in the region; Russia has strengthened its position as a regulator of the conflict, as mediator and guarantor of the agreement. On the other hand, however, the region is much more ‘deregulated’ and unstable than it was before the war: the ceasefire on the Karabakh front is based on a document of low formal status, as the real peace process is still frozen; the sense of satisfaction among all the participants (especially Baku and Ankara) is at an unsatisfactorily low level in relation to the ambitions awakened within their societies. Finally, the impression that the entire regional order is being undermined is not waning as the Turkish-Russian rivalry grows and – on the other hand – the role of the West and Iran, which played practically no role during the conflict or the year since its end, is marginalised.

It is therefore unlikely that the current state of suspension will persist for much longer. It seems to be in Russia’s interest to revive the political process that it favours (in which Moscow has a much stronger position, and which moreover would allow it to consolidate its gains) and marginalise Turkey; Azerbaijan and Turkey, in turn, may return to the politics of force and facts on the ground achieved at Armenia’s expense, in line with their incompletely realised ambitions. At the same time, the situation around the conflict may be influenced much more now than before 2020 by tensions between Russia and Turkey in other areas (Syria, Libya, Ukraine and the Black Sea region), and by developments in the Iranian crisis.

The conflict chilled, but not frozen

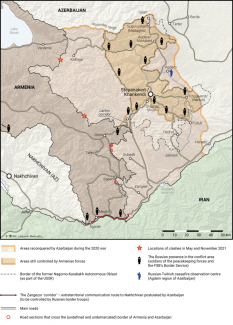

The current situation in the conflict area is the result of the so-called second Karabakh war, which was fought from 27 September to 10 November 2020. As a result of the victory for Azerbaijan (supported by Turkey) and the defeat of Armenia (which Russia saved from even greater losses), the balance of power has changed, not only between Baku and Yerevan, but also between Moscow and Ankara, and between them and the West, which is becoming less and less important in the region. The military action was ended by the mediation of the President of Russia, Vladimir Putin. Pursuant to the Statement signed by him and the leaders of Azerbaijan and Armenia, the parties halted their advance at the positions they had reached during the ceasefire. Therefore, the southern part of Nagorno-Karabakh itself, including the militarily and symbolically very important city of Shusha, has remained with Azerbaijan. It is true that the majority of Karabakh (including its capital Stepanakert, in Azerbaijani: Xankəndi) remains in Armenian hands – the unrecognised ‘Republic of Nagorno Karabakh/Artsakh’, closely linked to Armenia, still exists – but all the ‘occupied territories’ surrounding it have now come under Baku’s control.[2] As a result, after almost 30 years Azerbaijan has regained access to the whole of its border with Armenia and Iran.

On the basis of the Statement, a contingent of Russian peacekeepers, numbering 1960 soldiers, was sent to the site. They were deployed along the line separating the positions of the parties in Nagorno-Karabakh and in the Lachin ‘corridor’, which ensures communication between Karabakh and Armenia.[3] The overall number of Russian soldiers in the conflict area is actually higher, although the exact figure is difficult to specify. These are mostly officers of the Ministry for Emergency Situations and the Border Service of the Federal Security Service (FSB).[4] According to the arrangements, the peace contingent should remain there for five years (until November 2025); this period is to be automatically extended by another five-year periods, if no party lodges an objection to it up to six months before its expiry (Baku has already indicated that it will demand that the Russians withdraw). According to another provision, a Russian-Turkish observation centre was established in the Agdam region of Azerbaijan on 30 January 2021 to monitor the ceasefire.[5] This fact confirms Turkey’s growing influence in the South Caucasus, something which Russia must take into account.[6]

The provision for the exchange of all POWs, hostages and other detainees and the bodies of the fallen has only partially been completed. According to Yerevan, Azerbaijan is still holding about 200 Armenian prisoners of war: Baku says these are people captured after the ceasefire who committed common crimes. Azerbaijan has released POWs in groups of around 10 to 20 persons, thanks to external mediation (Russian, American, Georgian), as well as in exchange for maps of minefields of areas which have successively come under Baku’s control.[7] Azerbaijan has been using its Armenian prisoners as a means of putting pressure on Yerevan, and as a bargaining chip in their negotiations.

The last point of the Statement remains unrealised; this refers to the unblocking of all transport and communication routes in the region,[8] including between the core territory of Azerbaijan, the Nakhchivan Autonomous Republic (separated from it by the territory of Armenia) and Turkey. It was stated that Armenia would guarantee the safety of transport in this section, which would be controlled by the Russian Border Service. On the basis of another statement signed in Moscow by Aliyev, Pashinyan and Putin on 11 January 2021, a working group was established under the chairmanship of the three countries’ deputy prime ministers, which was tasked with preparing a list of steps to unblock the routes by 1 March. However, despite the group’s regular meetings – the last one was held in October – it has not been possible to draw up or approve such a list.

One year after the end of the war, the truce set out in the tripartite declaration is generally being respected, although the situation in the conflict area can be described as tense and unstable. Armed incidents take place regularly, but they are of relatively low intensity, and generally occur along the undefined and undemarcated border between Azerbaijan and Armenia, and not around Karabakh.[9] There are many indications that they are more often provoked by the Azerbaijani side. In September 2021, Azerbaijan unilaterally set up border checkpoints on the road connecting the towns of Goris and Kapan in the south of Armenia: this route, which crosses the territory of Azerbaijan for a short distance, is the main artery linking the south of the country with Yerevan, and Iran with Armenia & Georgia.[10] In November, Azerbaijani customs checkpoints appeared on this and another road. These steps are intended to force Armenia to agree to open land transit to Nakhchivan. The dispute concerns the rules of operation for this route, as well as terminology. Baku speaks of the Zangezur ‘corridor’, while Yerevan only agrees to refer to it as a ‘road’ or ‘trail’, because the word ‘corridor’ would assume extraterritoriality, and this concept does not appear in the Statement.[11] (Iran is also opposed to the creation of a ‘corridor’, as it is afraid that such a route could intersect the north-south road, which is important for it.) In addition, Baku wants the road to run along Armenia’s border with Iran, while Yerevan would prefer it to be deeper in-country.

The landscape after the battle: Azerbaijan, Armenia, Georgia…

Contrary to the status quo ante, which clearly suited one side of the conflict – Armenia with the ‘Nagorno-Karabakh Republic’ – and Russia, the current state of affairs does not fully satisfy any of the actors involved, even Azerbaijan, which showed that it had the real power to pursue its interests (the victory in the war was a mental breakthrough, erasing some of Azeri society’s trauma after the defeat of the early 1990s). Admittedly, in Baku’s official rhetoric, the conflict has been resolved and the state’s territorial integrity has been restored;[12] however, Azerbaijan still does not control most of Nagorno-Karabakh itself, Russian peacekeepers have appeared in the country (Russia would prefer to maintain its presence for a longer period of time – and is taking steps to bring this about)[13], and finally, Azerbaijan has not managed to have its important communication routes to Nakhchivan and Turkey unblocked. Moreover, in many fields Azerbaijan is becoming increasingly dependent on Turkey, whose help was instrumental in its victory.

President Aliyev, whose position in society as a victorious leader has been greatly strengthened, has become a hostage to this success. He now has to cope with his public’s awakened expectations – including the imminent reconquest of the rest of the disputed territories – and has limited room for manoeuvre; his options are influenced not just by the Russian military presence, but also by the Turkish factor. On the basis of available information, it is not possible even to estimate the extent of Turkey’s influence in the Azerbaijani army; nevertheless, both among them and among Azerbaijan’s other state institutions, there is no doubt that a generation has risen to prominence for whom Turkey remains a civilisational model and reference point. Therefore, it remains possible that Baku will make future attempts to counterbalance Ankara’s influence by periodically reviving its relations with Russia. However, it seems less likely that it will attempt to make even individual attempts to move closer to the West (in keeping with the state policy of remaining equidistant between Euro-Atlantic and Eurasian structures, as well as the West’s principled position regarding the observation of human rights).

Armenia lost the war and, in addition to its losses in people and military equipment, it also lost the advantage of holding the ‘occupied territories’, which came as a great shock and disruption to the Armenian people both inside and outside the Armenian state. Despite attempts to overthrow Prime Minister Pashinyan, who was blamed for the defeat, he managed to retain power. Armenian forces still control a major part of Nagorno-Karabakh, and the Lachin ‘corridor’ enables continued communication with Stepanakert. And regardless of the country’s dependence on Russia, now greater than it was before the war (thanks to the presence of the peacekeepers – who are now guarantors of the truce – and an increased contingent of Russian border guards), Yerevan does still have some potential room for manoeuvre in the longer term. It was most likely the threat to ‘fold up’ the informal Russian ‘umbrella’ over Nagorno-Karabakh (which proved ineffective) that prevented the Armenian government from signing an association agreement with the EU in September 2013. In the further future, if Russia’s position in the region weakens, the lack of the ‘burden’ of Nagorno-Karabakh – without which the Armenian state can still keep functioning[14] – would give hope for Yerevan to pursue a more rational, burden-free and diversified foreign policy.

The outcome of the war has increased Georgia’s dependence on the Turkish-Azerbaijani duo, and could potentially increase the threat from Russia – which has extended its military presence into another country adjacent to Georgia. This is especially dangerous in view of the growing conflict between Tbilisi and the EU & the US.[15] Georgia cannot oppose either the ‘pan-Turkish’ domination or any potential hostile actions by Moscow, and so it has attempted to improve its position by offering Armenia and Azerbaijan its good offices, as well as a platform for meetings and dialogue. Prime Minister Irakli Garibashvili has been involved in arranging prisoner exchanges, and delivered a message to the Turkish President from the Prime Minister of Armenia, among other actions. The possible unblocking of transport routes through Armenia will not have a particular impact on Georgia’s unique position as an essential element of the regional networks along both the east-west and north-south lines.

…Russia, Turkey, the West, Iran

The last Karabakh war also significantly changed the context in which the conflict, and indeed the entire South Caucasus, functioned. The basic mechanisms regulating regional security issues were called into question, as were the roles played in the region by neighbouring countries – primarily Turkey, but also Iran.

Before 2020, Russia’s domination of the regional security situation was an unspoken certainty. Even if Moscow was unable to impose its will directly, it was still ready and able to block any actions taken against its interests (for example, Georgia’s attempt to regain control over South Ossetia in 2008). With regard to the Karabakh conflict, this domination was strengthened by the following factors: Russia’s military alliance with Armenia; its military presence in this country; its ability to influence the balance of power between Armenia and Azerbaijan by delivering weapons to both countries; and finally, the effective instruments it could use to put pressure on local elites and societies (including through their diasporas living in Russia and its soft-power potential). Moreover, Russia acted as a formal mediator in the dispute (as co-chairman of the OSCE Minsk Group, but also in the tripartite format). The West, which was present to different extents in individual countries, also remained an important element in maintaining the regional balance; it effectively shaped the entire region and mitigated military tensions, and was also involved in the Karabakh peace process (including as part of the Minsk Group). Meanwhile, the war – which went on for a long time in the face of Russian passivity – proved that Azerbaijan was willing and able to change the balance of power militarily, ignoring the mechanisms previously adopted; it also struck a blow at Moscow’s roles as a ‘guarantor’ of stability and an ally of Armenia. The key factor behind the change in the balance of forces, however, seems to be Turkey’s revelation of its strategic position and regional ambitions. Turkey has developed a network of very close ties with Azerbaijan over 30 years, and it was these, with Ankara’s direct political and military support (at least at the level of equipment and advisers), which allowed Baku both to take the risk of conducting a relatively long military campaign and to achieve its victory. Thus, both the war of 2020 and the year that has passed since its end reflect, to a great extent, a new stage in the history of the Karabakh conflict and the region as a whole, in which Russian-Turkish rivalry now plays a key role.

At the present stage of the game, Russia seems to be playing more effectively. Although it only entered the conflict after some delay, it was Moscow (without the formal participation of Turkey) which imposed the conditions of the ceasefire and has been their main guarantor since then. Thanks to the war, it succeeded in introducing peacekeepers to Karabakh after many years of efforts; it significantly increased its control over Armenia’s security policy (almost incapacitating it strategically); and finally recognised the growing importance of Azerbaijan, accepting the gains it has made. At the same time, Russia has marginalised Turkey’s role in the political process while not antagonising it openly, and strengthened its own position vis-à-vis the West. In the logic of the past 30 years, the current situation should be seen as a significant boost to Russia’s position in the region, confirming the decades-long adjustment to the balance of forces in the Karabakh conflict in Azerbaijan’s favour. In this perspective, the weakness of the current ceasefire’s foundations – that is, the Statement, which imposes a deadline of at least four and a half years within which the peacemaking forces’ presence could be terminated – could also become an asset for Moscow; it could become able to regulate the dynamics and boundaries of the regional processes according to its own needs. However, this temporary stability, including Russia’s relative successes in managing the situation, will not determine its strategic success, nor will it be able to successfully defend (let alone strengthen) its authority in the Caucasus in the long term, or to permanently block Turkey’s ambitions. The fact is that at the moment, the political effects of Turkey’s involvement and Ankara’s calculations are limited: Turkey had no influence on the drafting of the Statement which ended the fighting; the mandate of the Turkish forces in the conflict area is limited (to the observation centre); and finally, the new communication routes between Turkey and Azerbaijan have not been opened. Moreover, Turkey has not strengthened its presence in the existing peace formats, and the Turkish proposal for a new regional format (‘3 + 3’, i.e. the Caucasus states, Turkey, Russia and Iran) has not been adopted. On the other hand, however, the war made real and significantly strengthened the often underestimated potential of Azerbaijani-Turkish cooperation at the political, institutional and military levels, as well as the power of Turkey’s links and influences on Azerbaijan’s elite and society (the younger generations are oriented towards Turkey, not Russia). The participation of President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan as a co-host in the victory parade on 10 December 2020 in Baku was a symbolic confirmation of these processes[16] (Azerbaijan is trying to make its relationship with Ankara into a true partnership, as it earnestly wishes to avoid being perceived as the ‘little brother’ in the relationship).

With the seemingly satisfactory ceasefire in Karabakh, Turkey’s military presence in Azerbaijan is increasing, both in the form of the presence (whose extent is hard to assess) of advisers or entire military units/bases, as well as spectacular manoeuvres involving Turkish forces in the Caspian Sea, and also joint Turkish-Pakistani--Azerbaijani and Turkish-Azerbaijani-Georgian military manoeuvres. The mental aspects of the Turkish involvement in Karabakh are not readily measurable, but could prove to be crucial: Turkey is the first country outside the former USSR to take the lead in a regional conflict that ended in (limited) success and significantly strengthened its authority within the region, and within the Turkish-speaking and Muslim environment of the Caucasus more broadly. It should be assumed that the foundations of the Turkish presence in the region and the processes stimulated by Ankara have not been weakened or rendered obsolete, but in fact have actually been strengthened. The state of suspension achieved on 9–10 November does not satisfy Ankara in the least, and Russia’s position will not hinder Turkey’s ambitions either (considering the long list of Russian-Turkish conflicts in Syria, Libya, the Black Sea and others, intertwined with effective cooperation between the two countries).

The scale of uncertainty as to the dynamics and directions in which Russian-Turkish relations in the Caucasus may develop is exacerbated by the significant reduction of the Western factor in the region. Neither the EU nor the US played a significant role, either during the conflict itself, or throughout the stages of the post-conflict situation. This means – despite the achievements, potential, authority and rich arsenal of instruments which the West (both the EU and the US) could have brought to bear – it has proved incapable, or reluctant, to control the situation. It has also (at least at this stage) ceased to be an important point of reference for the region’s states, as it showed itself unable to prevent an unfavourable revision of the political order in its neighbourhood. On the other hand, Iran’s attitude represents the changes that have taken place in the region, and the fears of what could happen in the future. First, the only strategic communication route leading north from this country (via Armenia) has been threatened: Azerbaijan and Turkey’s pressure on the ‘corridor’ increases the risk of Iran becoming isolated from Armenia. Secondly, closer cooperation between Azerbaijan (with which Iran’s relations are traditionally bad) and Turkey (with which Iran has traditionally and tangibly competed, for example in Syria) – with the participation of Pakistan – poses a strategic threat to Tehran, both through its possible isolation and the potential to destabilise the north of the country, which is inhabited by a large Azerbaijani minority. Azerbaijan’s close military cooperation with Israel only adds to Tehran’s fears. In this perspective, Iran is becoming both an object and a potential subject of the escalating situation in the South Caucasus.

Future challenges

The year that has passed since the end of the second Karabakh war has brought relative stability to the conflict area; moreover, despite the periodic escalations in tensions, the revision of the regional order which Azerbaijan and Turkey had been working on has been frozen. However, this state of affairs does not correspond to the ambitions of the individual players, nor does it secure their achievements so far; finally, it is based on a makeshift Statement, which – while extremely effective so far – has still not been fully implemented. The current state of suspension – the temporary freezing of the conflict – will therefore be difficult to maintain in the perspective of even the next twelve months; and it will be impossible after 2025, when the mandate of the Russian peacekeeping forces expires.

The first main path along which the situation could develop involves the effective freezing of the conflict’s status quo by Russia, which wants to preserve or restore its domination of matters concerning the conflict (and the Caucasus as a whole). In practice, Russia would have to force through the revival of the peace process – on the basis of the Statement in the tripartite format or the Minsk Process – and marginalise Turkey in this process (in a manner analogous to the Statement or, for example, the Astana process relating to Syria). The basic condition for such a scenario would involve Russia demonstrating its determination as a mediating force; this would involve actively discouraging Azerbaijan from using armed force and insisting it cool down its relations with Turkey. By analogy with the situation over the past 25 years, we should not expect an unequivocal finalisation of the peace process (including a definition of Nagorno-Karabakh’s status); however, we should not rule out a return to military action to adjust the balance of power either. Therefore, the scenario of a temporary freeze to the conflict, rather than a resolution in which Russia participates, would be more realistic in this respect.

An alternative scenario involves Turkey and Azerbaijan making a further revision of the regional order, through a policy of fait accompli – putting de facto political and military pressure on Armenia – running the risk of an outbreak of open hostilities. In practice, this would mean intensifying military pressure to unblock the communication routes (in other words, the Statement will either be implemented in full or completely undermined) and the disputed border sections between Armenia and Azerbaijan. In a milder version, Armenia could be put under pressure if the Turkic duo bypasses the Russian forces (in a similar manner to the Turkish-Russian tensions in Syria). However, in the most extreme variant – for which Ankara would be readier than Baku – the Turkic powers could also direct their military pressure at Russian forces. In this variant, the situation would be improved by working contacts between the presidents of Russia and Turkey, depending on how Turkey and Russia come to make deals in other fields; any such resolution would also most likely be achieved at the expense of Armenia. This path would be a more turbulent variant of the formation of a real Russian-Turkish condominium in the region, which would also be in Turkey’s interest.

The calculations of the actions Moscow and Ankara have taken around the Karabakh conflict – the main drivers of the first and second options respectively – will undoubtedly be significantly influenced by the development of Turkish-Russian relations overall, including the degree of tensions in their relations with the US and the EU. In the regional context, Georgia occupies a significant (though essentially passive) position, as its stability is a condition for the development of Turkish-Azerbaijani cooperation; the country is an essential communication corridor and, at least due to the oil and gas pipelines running through it, it has great strategic importance). Finally, the evolution of the situation in Azerbaijan (including the public sentiment there and the president’s calculation of the risks involved) – and, to a much lesser extent, in Armenia – remain open questions.

Map. The Nagorno-Karabakh conflict area as of November 2021

[1] This Statement (marked in the text with a capital letter) was signed by Presidents Vladimir Putin and Ilham Aliyev and Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan, separately and remotely.

[2] Some of the ‘occupied territories’ were conquered during the fighting; others were handed over by the Armenians after the war.

[3] Currently (November 2021), only people registered as resident in Nagorno-Karabakh can move there without any restrictions. Residents of Armenia must obtain a special permit, and foreigners are not allowed to travel there.

[4] On 13 November 2020, President Putin signed a decree establishing an inter-ministerial centre to resolve the humanitarian problems and rebuild the civilian infrastructure in Nagorno-Karabakh; this body included representatives of the Russian Ministry of Emergency Situations among others. In turn, on 20 November 2020, the director of the FSB stated that at the request of the Armenian side (and after informing Azerbaijan), 188 additional Russian Border Service soldiers were sent to Armenia with the task of creating checkpoints along the border with Nakhchivan (Russian border guards have been stationed in Armenia since the 1992 agreement) and other places. In May 2021, Armenia allocated plots of land and real estate in the south of the country to the FSB (as a gift).

[5] The formal basis for the centre’s establishment and operation was an agreement between the heads of the Russian and Turkish defence ministries, signed on 1 December 2020. Outside the centre, a certain number of Turkish soldiers – also difficult to assess – are permanently based in Azerbaijan. These include various types of instructors, some of whom were most likely present during the military operations.

[6] W. Górecki, ‘Rywalizacja poprzez współpracę. Rosyjsko-tureckie centrum obserwacyjne na Kaukazie’ [‘Competition through cooperation. The Russian-Turkish observation centre in the Caucasus’], OSW, 2 February 2021, osw.waw.pl. On 1 February 2021, the former Russian president Dmitri Medvedev stated that Moscow ‘cannot ignore’ the Turkish factor in its policy towards the region.

[7] By 19 October 2021, Azerbaijan had handed over 113 prisoners of war to Armenia, and Armenia 15 to Azerbaijan. Н. Булгадарян, ‘Еще пятеро пленных вернулись из Азербайджана в Армению’, Радио Азатутюн, 19 October 2021, rus.azatutyun.am.

[8] The only exception is flights from Baku to Nakhchivan, which currently fly over Armenian airspace: previously, Azerbaijani airlines used Iranian airspace (a longer route).

[9] The first case of death since the end of the war was that of an Armenian soldier (he died on 25 May 2021). The most serious clashes took place on 16 November in the middle section of the border between Armenia and Azerbaijan.

[10] Drivers are now able to use the modernised alternative road (via Tatev).

[11] However, the Statement does refer to the Lachin ‘corridor’. In connection with this, Baku has demanded that the Zangezur ‘corridor’ should also be officially referred to as such, in analogy with the former.

[12] On 24 September 2021, Azerbaijan’s President Ilham Aliyev called on member states and the UN Secretariat not to use the name Nagorno-Karabakh, as there is no longer an administrative-territorial unit with that name in Azerbaijan. ‘Алиев призвал страны мира не использовать название «Нагорный Карабах»’, ТАСС, 24 September 2021, tass.ru

[13] Even those few Russian experts who claim that Russia emerged from the Second Karabakh war in a weaker position believe that Moscow will do everything to ensure that the contingent remains in the conflict zone after 2025: this particularly concerns the process of ‘passporting’, i.e. granting Russian citizenship to Karabakh Armenians. Р. Пухов, ‘Россия как главная проигравшая сторона во второй карабахской войне?’ [in:] Р. Пухов (ed.), Буря на Кавказе, Москва 2021, pp. 39–47.

[14] In official rhetoric, the unity of the Armenians of Armenia and Nagorno-Karabakh remains axiomatic. In practice, however, one can speak of a certain ‘Karabakh fatigue’ in Armenia; one sign of this may be seen in the results of the early parliamentary elections on 20 June 2021, in which the bloc of the former president Robert Kocharian, who was associated with the greatest Armenian successes in Karabakh and was opposed to making any concessions in favour of Baku, clearly lost ground to the party of PM Nikol Pashinyan, who sponsored the ceasefire and announced further dialogue with Azerbaijan and Turkey

[15] W. Górecki, ‘Gruzja: narastający kryzys w relacjach z Zachodem’ [‘Georgia: growing crisis in relations with the West’], OSW, 3 September 2021, osw.waw.pl.

[16] President Erdoğan has twice visited the areas recovered by Azerbaijan. On 26 October 2021, together with President Aliyev, he participated in the opening of an airport in Fuzuli (Füzuli).