Nord Stream 2 divides the West

In recent weeks the US has stepped up its campaign against the Nord Stream 2 project. Washington is putting pressure on Berlin to withdraw its support for the project, and is threatening to use increasingly powerful measures, including sanctions on European companies involved in the gas pipeline’s implementation. The growing dispute between the US and Germany over Nord Stream 2 has become an element of the broader controversy surrounding the project in the EU and is leading to deeper divisions between the member states. It has brought to the fore the differences in approaches to gas cooperation with Russia as well as approaches to the development of Russia’s strategic gas pipeline projects. While Germany, but also Austria, the Netherlands and a number of other countries, limit their approach to commercial issues, Poland, the Baltic States, Denmark and the US also see it as having security implications which do not only relate to energy. The conflict over Nord Stream 2 is also part of the game concerning the future shape of the gas market in Europe, and the roles played by individual external suppliers (mainly Russia, but also to an increasing extent the US) and companies such as Gazprom and its European partners. The Nord Stream 2 case has become a major challenge of the EU’s cohesion and its relations with the US and Russia.

Gameplay on Nord Stream 2 brings short term political benefits to Russia. The project has not only caused a rift between the EU member states, it has also become a source of increased friction in transatlantic relations. The actions taken by Washington and Berlin with regard to Nord Stream 2 will have the greatest impact on its future. Although Berlin has changed its rhetoric and Chancellor Merkel has acknowledged that project has a political dimension in addition to the commercial one, Germany is unwavering in its support for NS2, trying to limit its negative consequences to problems regarding Ukrainian transit. Thus Berlin does not refer to the strategic concerns of the Central European and Scandinavian countries, the European Commission (EC) and the US which are not related directly to Ukraine.

America’s tough game against Nord Stream 2

The US has been opposing the implementation of Nord Stream 2 since the project was announced in 2015 during Barack Obama’s administration. During the presidency of Donald Trump, the US's stance on the matter has become entrenched. There are at least two reasons for the current US opposition to Nord Stream 2. First of all, the US perceives the project as a challenge to Europe’s energy security, and the EU’s new gas links with Russia as hindering diversification of the gas supply, and also the stability and security of Europe, especially Central and Eastern Europe. The current administration is thus continuing the traditional US policy towards new gas pipelines linking Russia and Europe. The opposition to Nord Stream 2 as a challenge to European security has become particularly relevant in the context of Russia’s annexation of Crimea and the Russian-Ukrainian conflict in Donbas. The US position on the project is confirmed by statements of representatives of the State Department, including by both the current and previous US Secretary of State.

Secondly, Washington’s opposition to NS2 could help accomplish the Trump administration’s energy policy goal, which is to increase exports of US LNG – including to the European market. The support for domestic exports is in part testified by the comments made by Donald Trump (for example, during his visit to Poland and during the US-Baltic summit), and by the Secretary of Energy. According to them, a higher level of US LNG exports could contribute to the diversification of supplies in Europe and a reduction on the dependence on Russian supplies, mainly in Central & Eastern Europe.

The key American instrument impacting on Nord Stream 2 implementation is the so-called CAATSA[1] - the sanctions package imposed on Russia in 2017, affecting, among other things, the Russian energy sector and existing or planned export pipelines from Russia (among them Nord Stream 2, the only project referred to by name). Germany, a range of other European countries, and the European Comission[2], protested against the US law introducing the sanctions. As a result of European, including German, lobbying efforts, the document and State Department instructions on CAATSA implementation, was supplemented by the provision that the potential launching of sanctions should be “in coordination with allies”, but ultimately the US president has the right to decide to impose them by himself.

In recent months, the likelihood of CAATSA being imposed on European firms involved in Nord Stream 2 has increased[3]. This is illustrated by the increasingly frequent warnings, e.g. on 17 May in Berlin, Deputy Assistant Secretary at the Bureau of Energy Resources, Sandra Oudkirk said that the US was “exerting as much persuasive power as we possibly can” to stop the project, and reiterated the possibility of sanctions. European diplomats also consider sanctions likely.

Nord Stream 2 is also the subject of increasingly intensive American political efforts. It became one of the subjects discussed by the US president with EU leaders (Trump discussed NS2 with presidents of the Baltic countries and Chancellor Merkel). According to media reports Trump was to offer Merkel a return to negotiations on a new EU-US trade agreement[4] if Germany withdraws its support for Nord Stream 2. US diplomacy activity on the project has also intensified in recent months. State Department officials have been openly criticising Nord Stream 2 in Brussels and Berlin, calling upon member states to oppose the project, and encouraged some of them, for instance Denmark and Sweden, to take measures to hamper NS2 implementation. Security challenges in the Baltic Sea area have also been raised publicly, such as the greater risk of surveillance by Russian intelligence once Nord Stream 2 is constructed (surveillance equipment on the Baltic Sea bed)[5]. It has also been reported that Trump might try to introduce the issues of gas and imports from Russia to the NATO discussions agenda [6].

At the same time, US efforts to support the diversification of gas supplies in Europe are continually visible. The construction of new LNG terminals, for instance in Croatia and Greece, supported by US diplomacy, could enable increased EU imports of LNG, including from the US. In addition, the Americans have also been unequivocal in their support for other European diversification projects such as the Southern Gas Corridor and the Baltic Pipe, and interconnections integrating the European market (among other things for the Slovak-Ukrainian interconnector which enables Ukraine to import gas from the EU). US companies have also been involving in new European exploration projects (e.g. on the Romanian Black Sea shelf at present).

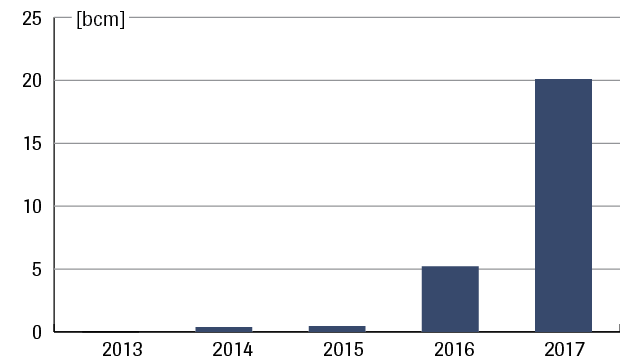

The actual volume of US gas exports to Europe is determined by commercial decisions made by the private US firms selling LNG and the prices on global markets. Although US LNG exports to Europe rose in 2017 in comparison to 2016, it still represents a negligible portion of the EU’s overall needs – less than 1% of total imports – and cannot be compared with supplies from Russia, Norway, or Algeria. America’s most important gas importers remain Mexico, South Korea, and China (see diagrams 1, 2 and 3). In the first months of 2018, higher prices and demand resulted in rising US LNG exports to Asian countries, while only three cargos arrived in the EU.

Diagram 1. Sources of gas imports to the EU, 2017

Source: Eurostat

Diagram 2. US LNG exports in 2013–2017 (bcm)

Source: www.eia.doe.gov

Diagram 3. Directions of US LNG exports, 2017

Source: www.eia.doe.gov

Feigned change in the German policy towards Nord Stream 2

Since the Gazprom and five Western European companies announced their plans to build Nord Stream 2 in June 2015, German diplomacy has supported the project and sought to implement it in its original form – as an extraterritorial gas pipeline. Germany wished to minimise the European Commission’s role in Nord Stream 2 matters and opposed US involvement in project-related issues. US criticism of Nord Stream 2 and the actions undertaken (including sanctions against Russia, potentially affecting the project’s implementation) were interpreted as threatening not only German interests but also the EU’s entire energy policy, motivated by a desire to support the export of US LNG to the EU[7]. On the other hand, the German government, especially the Social Democrats, were seen to be continually lobbying in favour of Nord Stream 2. From 2015 until 2017, representatives of the German government attended 62 meetings related to the project. Most heavily engaged was Sigmar Gabriel, the former German minister of economic affairs and energy, and subsequently foreign minister[8].

Germany’s support for NS2 construction did not wane when a new coalition CDU/CSU-SPD government was formed in March 2018, in which Peter Altmaier (CDU) took up the post of economic affairs minister, and Heiko Maas (SPD) became foreign minister. There was however an evident change of the German rhetoric related to the project’s implementation, signalled by Angela Merkel (CDU) on 10 April at a meeting with Ukraine’s president, Petro Poroshenko, in Berlin. The Chancellor stated then that, apart from economic issues, political factors also had to be taken into account when assessing the Nord Stream 2 project. Merkel pointed out the negative implications for Ukraine of decreased revenue from the transit of Russian gas, stating that Nord Stream 2 could not go ahead if Germany did not receive guarantees regarding the future of Ukrainian transit. She made a similar announcement during talks with the Russian president, Vladimir Putin, and the Danish prime minister, Lars Løkke Rasmussen. In a written response to a parliamentary question on 14 May this year, we read that the German government has been taking decisive measures to obtain guarantees of the continued transit of Russian gas through Ukraine once the current agreement expires and that it supports European efforts to bring this about. In May 2018, Germany intensified diplomatic efforts regarding Nord Stream 2 and the future of Ukrainian transit. Both issues were raised during talks with Russia and Ukraine (visits by Heiko Maas to Moscow, Peter Altmaier to Moscow and Kiev, and Angela Merkel to Sochi). However, no binding assurances from Russia were received on the continuation of Russian gas transit via Ukraine.

Berlin’s change of rhetoric regarding Nord Stream 2 was probably due to an increased risk of US sanctions and increasingly difficult relations with the US. The EU measures, (including an opinion issued by the EU Council’s legal service in March 2018 confirming the need to conclude an international agreement in the case of gas pipelines from third countries such as Nord Stream 2, and the exclusive competence of the commission to negotiate it), and a reshuffle in Germany (both in the federal government and in the SPD), might also have influenced Berlin. Berlin only slightly bowed to of the project, by seeking a solution to the only political problem officially acknowledged on its part (Ukraine as a transit country); it still wants the project to go ahead. At the same time, Germany is hoping to ease the tension in relations with the European Commission – whose involvement in Nord Stream 2 related issues cannot be avoided, and which can be seen as a potential ally in some areas relevant to Berlin, such as relations with the US in the NS2 case. It seems even more probable given that one of pivotal political goals of the EC is to guarantee the maintenance of transit via Ukraine. This is being promoted, for example, in trilateral talks with Moscow and Kiev.

The German government’s diplomatic offensive in May has demonstrated that Germany wishes to act as a mediator between Russia and Ukraine on the transit issue, while remaining a party directly interested in Nord Stream 2 going ahead. It is unclear whether its efforts in this regard have been agreed upon with the EC; Berlin’s specific objective and negotiation strategy regarding Ukrainian transit are also clouded. It cannot be ruled out that, having obtained Russia’s guarantee of the continued transit of minimum gas volumes, Berlin will try to neutralise Kiev’s resistance and present this as a success on the EU forum.

The EU vs US-German games on Nord Stream 2

Since 2015, the EU has been starkly divided over Nord Stream 2. Recent events relating to the project have exacerbated the dispute. Supporters of the projects – above all Germany, but also Austria, France, and the Netherlands – see it primarily as a business venture and see forging better gas relations as an instrument facilitating the cooperation and restoration of both trust and good political relations. On the other hand, opponents of the project – Poland, the Baltic states, Slovakia, Denmark, and recently also the United Kingdom - believe that in addition to posing a threat to those countries’ interests (impacting their gas markets’ development, planned diversification of supply, gas prices, and transit role) the construction of the gas pipeline will also challenge energy security across Europe and security in general. This is also the position of the EU’s neighbour, Ukraine. Ukraine is particularly keen to halt the scheme as it undermines its central role as a transit country for Russian gas to the EU.

Countries resisting NS2 see risks for the EU in Russia’s actions, preventing constructive, trust-based cooperation, including in the gas sector. The European Commission also opposes Nord Stream 2 due to the potentially detrimental impact on the security of supply, competitiveness, and integration of the EU gas market, the unclear legal framework, as well as due to the political divisions the project has already generated in the EU. In order to establish a clear legal regime for the project and ensure it is subject to EU law, the commission initiated at the end of 2017 a process of seeking a mandate from the member states to negotiate an international agreement with Russia on Nord Stream 2 and to amend the gas directive of 2009. EC attempts were protested against by a range of member states, including Germany, which de facto questioned the EC’s competence with regard to the project, and contributed to hampering EU work on the amendment to the directive.

Consequently, US opposition and its actions with respect to Nord Stream 2 became part of a vivid and deep intra-European dispute regarding the project and deepened the earlier antagonism between the member states. The US are perceived by some as almost the only hope for blocking the unwanted gas pipeline, while by the others it is accused of an unscrupulous and unacceptable promotion of its own export interests (these arguments are usually made by Germany and the European companies involved in Nord Stream 2). It is symptomatic that those accusing the Americans of politicising gas relations with the EU and promoting its own LNG exports disregard the predominantly private ownership of the US gas sector and they also defend the commercial nature of Nord Stream 2, carried out by the Russian state-controlled Gazprom.

The change in rhetoric of the new German government with regard to Nord Stream 2 has been noted and welcomed in Brussels. As a result, the EC offered Germany to join the trilateral EU-Russia-Ukraine talks aiming to devise the rules for Russian gas transit through Ukraine after the expiration of the current transit contract in 2019, and also to discuss in the same format the controversial aspects of NS2[9]. Thus, Germany was the first EU country to have a chance of participating in the negotiations backed by the EU since 2014, and can share political accountability for any solutions devised. Despite this, no information has been made public as to whether Germany accepted the EC’s proposal, or about the role it would play in those talks. It is also unclear whether and to what extent Germany’s position with respect to the European Commission’s efforts to devise a clear legal regime for Nord Stream 2 has changed.

Russia and the tensions regarding NS2

Regardless of the mounting political pressure from the US and actions taken by the European opponents of NS2, the Russian government officials and Gazprom have demonstrated unswerving determination to bring the project to fruition. This is evidenced by both by the practical measures taken by Russian side (building subsequent sections of the onshore infrastructure for NS2 in Russia, obtaining further permits for construction of the offshore section of the gas pipeline and more – for more details see Appendix 1), and by Moscow’s and Gazprom’s political activity (for instance, the celebration of the 50th anniversary of the signing of the first contract for gas supplies to Austria).

To justify the need to build Nord Stream 2, Russia points to a systematic increase in gas transmission to European users via Nord Stream 1 and the growth of Russian gas exports to Europe in recent years (including mainly to Germany, Austria, and the Netherlands – see diagrams 3 and 4). Moscow treats US opposition to Nord Stream 2 and the prospect of increased US LNG export to Europe as a direct competition to their gas supplies and as aimed at undermining Gazprom’s position in the EU. At the same time, President Putin, representatives of the Russian government, and the management of Gazprom have all consistently emphasised since June 2015 their readiness to continue gas transit via Ukraine and to hold negotiations on this matter, while stressing that its economic viability is a prerequisite for reaching an agreement[10].

Diagram 4. Russian gas exports to the European Union 2011–2017 (bcm)

Based on FSU Argus data

Diagram 5. Russian gas exports to EU countries 2014–2017 (bcm)

Based on FSU Argus data

Due to the probable delays in the implementation of both Nord Stream 2 and TurkStream (Turkish Stream), and uncertainty over the future legal regime for gas pipelines (sections running through EU territory), Russia may still need access to Ukrainian transit capacity once the current transit contract with Ukraine ends in 2019 (see Annex 2). This would increase the chances of concluding a subsequent transit contract and reaching a compromise. However such a scenario would not diminish the chances of Nord Stream 2 being built, i.e. achieving one of the major strategic goals of Russia’s external energy policy.

The geopolitical manoeuvring surrounding Nord Stream 2 brings short term political benefits to Moscow. The project initiated by Russia, has not only managed to divide EU countries, but has also become a source of rising tension in transatlantic relations. Yet the final outcome of the dispute over Nord Stream 2 for Russia will depend primarily on further moves taken by the US. Keeping Washington’s opposition to NS2 solely at the political and diplomatic level, and the mere threat of the US imposing sanctions on companies engaged in the project, will probably not be sufficient to prevent its implementation. Moscow is hoping that the German government will not only continue its political support for Nord Stream 2 but also act as a diplomatic shield, mainly in the EU. Russia is also counting on further anti-American consolidation in Europe and beyond triggered by further unilateral actions by the US (and criticised in the EU) such as cancelling the Iran nuclear deal or the growing conflict in trade relations between the US and the EU due to President Trump’s tariffs on steel and aluminium. Nord Stream 2 would, however, very likely be halted should US sanctions be imposed directly on the project.

Conclusions

The Nord Stream 2 project has become one of the most important issues impacting on the shape of transatlantic and intra-EU relations. The crisis in transatlantic relations, the growing discord between Berlin and Washington regarding the Nord Stream 2 issue, the increasingly harsh actions of the US, and Germany’s determination to carry out the project, indicate that tension between Germany and the US will grow. Berlin’s policy with respect to Nord Stream 2 as well as the Trump administration’s actions, place the EU in a difficult situation, magnify the differences in interests and incongruity within the EU.

The future of Nord Stream 2 will essentially be determined by whether Germany bows to mounting pressure from the US and withdraws its political support for the project. The decision to do this could lead to the development of a more cohesive EU policy on the project, and at least partially alleviate tensions with the US. This in turn would hamper the implementation of Nord Stream 2 and complicate both German and EU relations with Russia.

Were the US to shift from threats to action, by imposing sanctions on European firms involved in Nord Stream 2, then this would have a much greater impact. It would probably lead to the suspension of the project. Despite any potential political guarantees from Germany or even the EU, sanctions would probably make European companies - active globally, for instance, Shell and Engie - to withdraw from the project. Potential US sanctions, despite the aligned interests of the US, some EU countries, and the EC in the NS2 issue, could however lead to a less flexible EU position and consideration of protective and retaliatory actions, that would deepen transatlantic discord.

Appendix 1. Status of Nord Stream 2 project’s implementation

a. progress:

- expansion of internal infrastructure in Russia necessary to launch the NS2 gas pipeline. On January 18, 2017 - on schedule – Gazprom completed construction of the Bovanenkovo – Ukhta 2 pipeline. In 2018, ahead of schedule, construction of the Ukhta–Torzhok 2 gas pipeline and the Gryazovets–Ust-Luga section could be completed (where gas will be directly injected into the offshore section of the gas pipeline);

- obtaining the complete set of construction permits for Nord Stream 2 in Germany, Finland, and Sweden; the first approvals have been issued in Russia as well, where Gazprom will obtain a full set of permits in the next few months;

- continuing support for the scheme and ongoing financial commitments on behalf of five European companies: Uniper, Wintershall, Engie, OMV, and Shell. Explicit political support for the NS2 project from Germany and Austria, as well as support from France and the Netherlands;

- political measures: since 2015, NS2 has been the subject of discussions by representatives of the Russian government and leaders of the European countries from which companies are directly involved in the project (Germany, Austria and France). Russia has also begun a diplomatic offensive in countries which are sceptical of it. Gazprom has been stressing the strategic importance of the project and the need for it to be carried out at frequent meetings with Western European partners and at international industry events.

b. problems and challenges:

- objections raised by the Polish Office of Competition and Consumer Protection prevented the Nord Stream 2 AG consortium from being created, and this led to a delay in devising the financing mechanism for the project. The scenario finally adopted shifts the entire financial burden onto Gazprom, which remains the sole shareholder in Nord Stream 2 AG. the agreements reached (April 2017) with European firms envisage on their part financial support in the form of loans to Nord Stream 2 AG. Gazprom has also increased its own spending on NS2 from RUB 102.4 bln (2017) to RUB 114.5 bln (2018) and plans to incur almost RUB 417 bln in loans and credit lines for investment purposes, which is almost one third of the company’s investment budget (a record level in the company’s history);

- despite statements made, contracts for construction work for the offshore section of the gas pipeline have not been concluded yet. In December 2016 only a letter of intent with the Swiss company Allseas Group S.A was signed concerning construction of the first line of the gas pipeline. Contrary to the signals, no new firms have joined the project;

- in June 2017 the European Commission launched the process to obtain a mandate from the member states to negotiate an international agreement with Russia on the legal regime for the gas pipeline, in an attempt to make NS2 subject to EU energy law in the broadest scope possible; in November 2017 it also initiated a legislative process to amend the gas directive adopted in 2009, which was supported by the European Parliament;

- on 30 November 2017 Denmark amended its Act on the Continental Shelf with respect to approvals by the Energy and Climate Ministry for the laying of pipelines and cables in Danish territorial waters; as of 1 January 2018 decisions of this kind depend upon an investment being in line with Denmark’s foreign & security policy interests;

- in May 2018 the Polish Office of Competition and Consumer Protection instigated further competition infringement proceedings against firms involved in the Nord Stream 2 project, suggesting that agreements on financing the project concluded in April 2017 were an attempt to circumvent the objections the authority raised in July 2016;

- in May 2018 environmental protection organisations NABU and Client Earth contested, in Germany and Finland respectively, construction permits and operation permits for the gas pipeline issued in those countries.

Appendix 2. Russia’s position on gas transit via Ukraine

The key for negotiating any new transit agreement with Ukraine will be Russia’s actual needs with respect to gas transit. Official statements from Gazprom representatives suggest the company is interested in the continued transit through Ukraine of a maximum of 10–15 bcm of Russian gas per year. However it cannot be ruled out that the company may be forced to enter into a contract for greater transit volumes than declared (40bcm or more) and longer viability (medium-term contract). It is possible that even once NS2 is constructed, Gazprom will not be able to use the full capacity of the pipeline. Although the future legal regime of NS2 remains unclear, the prevailing interpretation of EU law at the moment is that infrastructure passing through the territorial waters of Germany and Denmark should be subject to EU energy law, including to the Third Party Access (TPA) principle. Therefore, it cannot be ruled out that Gazprom might only have access to around half of the Nord Stream 2 capacity (27.5bcm), and the procedure for obtaining an exemption from EU law might be lengthy – perhaps lasting up to several years. Assuming one line of the TurkStream gas pipeline is launched and a constant level of Russian exports to European consumers continues, Gazprom would be forced to transit about 50bcm of gas through Ukraine for a number of years. in such a scenario, the company might be interested in concluding a medium-term contract (for example for five years) with the Ukrainian side for such a transit volume. This could be attractive for Ukraine (according to recent economic viability).

Diagram 5. Russian gas flows to Europe through Ukraine and Nord Stream 1, 2012–2017 (bcm)

Based on Gazprom’s data

[1] Countering America’s Adversaries Through Sanctions Act, US Department of Treasury, 2.08.2017.

[2] For more on this subject see S. Kardaś, I. Wiśniewska, Ustawa o amerykańskich sankcjach wobec Rosji, “Analizy OSW”, 4.08.2017 https://www.osw.waw.pl/pl/publikacje/analizy/2017-08-04/ustawa-o-amerykanskich-sankcjach-przeciwko-rosji

[3] For example R. Gramer, K. Johnson, D. De Luce, U.S. Close to Imposing Sanctions on European Companies in Russian Pipeline Project, “Foreign Policy”, 1.06.2018 http://foreignpolicy.com/2018/06/01/u-s-close-to-imposing-sanctions-on-european-companies-in-russian-pipeline-project-nord-stream-two-germany-energy-gas-oil-putin/amp/?__twitter_impression=true

[4] B. Pancevski, Trump Presses Germany to Drop Russian Pipeline for Trade Deal, “Wall Street Journal”, 17.05.2018, https://www.wsj.com/articles/trump-presses-germany-to-drop-russian-pipeline-for-trade-deal-1526566415

[5] A. Shalal, Russia-Germany gas pipeline raises intelligence concerns - U.S. official, Reuters, 17.05.2018, https://uk.reuters.com/article/uk-usa-germany-russia-pipeline/russia-germany-gas-pipeline-raises-intelligence-concerns-u-s-official-idUKKCN1II0V7

[6] J. Sicilano, Trump wants to make natural gas part of NATO discussions, “Washington Examiner”, 17.05.2018

[7] See Außenminister Gabriel und der österreichische Bundeskanzler Kern zu den Russland-Sanktionen durch den US-Senat, 15.06.2017, https://www.auswaertiges-amt.de/de/newsroom/170615-kern-russland/290664

[8] Brisante Nähe, “Die Welt”, 15.12.2017, https://www.welt.de/politik/deutschland/plus171601464/Brisante-Naehe.html

[9] Sefcovic proposes involving Germany in quadrilogue to ensure gas transit via Ukraine, Interfax Ukraine, 16.04.2018, https://en.interfax.com.ua/news/general/499349.html/

[10] Except in the case of categorical statements made by the head of Gazprom Alexey Miller: Миллер: Роль Украины в качестве транзитера газа сведется к нулю, “ВЗГЛЯД”, 6.12.2014, https://vz.ru/news/2014/12/6/719045.html